Ex-St. Louis Cardinal Bill White connects in memoir ‘Uppity’

Published 5:00 am Sunday, April 17, 2011

- Ex-St. Louis Cardinal Bill White connects in memoir 'Uppity'

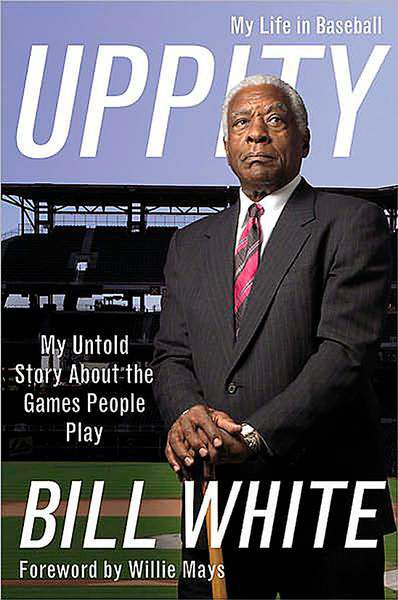

“Uppity: My Untold Story About the Games People Play” by Bill White with Gordon Dillow (Grand Central, 303 pgs., $26.99)

Bill White’s memoir is like one of his line drives — solid and direct.

White, who played eight seasons for the Cardinals, spends no time rhapsodizing about the game. Even if he had liked Fay Vincent, which he did not, White never would have been included in the former commissioner’s oral history, “We Would Have Played the Game For Nothing.”

White approached the game as a job and believes he was a better player for it.

In “Uppity,” he writes: “Being analytical, and emotionally detached, I was never nervous in the batter’s box or on the field. I gave a 100 percent effort, and if I didn’t get some kind of emotional high when I did well, on the flip side I wasn’t emotionally battered when I failed.”

White no doubt picked up some of that attitude from his mother and grandmother, who valued academics over sports.

Grandma, standing 4 feet 11 inches tall, dominated White’s extended family, which in the late 1930s migrated from the Florida Panhandle to Warren, Ohio, where the men found work in the steel mills.

White excelled in the classroom, enough to be offered a scholarship to Columbia University. Instead, he enrolled at nearby Hiram College because of its fine pre-med program.

White played enough baseball to earn a tryout with the New York Giants, and though his mother probably never forgave him for leaving college behind, White signed a contract for $2,500.

White’s first minor league stop was in Danville, Va., where he was the only black player in the Carolina League. Years later, White would wonder why baseball management didn’t send young black players to Northern cities. White had, of course, witnessed racism in Ohio, but the brand he saw in the South seared him, and he writes powerfully of its impact on him.

His skills made his stay in the minors short; in 1956, he was in New York City playing for the Giants and learning from Willie Mays.

White did a two-year stint in the Army and, when he rejoined the Giants, they were in San Francisco and Orlando Cepeda owned White’s position, first base. Waiting in the minors was Willie McCovey. Surely, that’s the greatest collection ever of first basemen in one organization.

White saw the writing on the wall and asked for a trade.

Giants general manager Chub Feeney, not used to players — particularly black ones — advising him on personnel moves, traded him to St. Louis.

White writes: “At the time, St. Louis was the worst city in the league for black players. We couldn’t stay at white hotels there, and couldn’t eat in the white restaurants.”

A few paragraphs later, though, White says, “Eventually it would turn out to be one of the best moves in my life.”

White’s hitting blossomed under the tutelage of Cardinal coach Harry Walker. He developed lasting friendships with the likes of Bob Gibson, and he began taking a leadership role on racial issues.

Though St. Louis was not without its racial faults (White needed the help of general manager Bing Devine and public relations executive Al Fleishman to buy a house), White directs real ill will toward St. Petersburg, Fla., where the Cardinals trained.

Black players could not stay at the team’s hotel, the Vinoy Park, and could not eat in most restaurants. White blew up when the St. Pete Chamber of Commerce invited all of the white players, including those who hadn’t even made the team, but none of the black players to an annual breakfast.

White told an Associated Press reporter how he felt, and the story went nationwide. A newspaper in East St. Louis suggested a boycott of beer produced by the team’s owner, Anheuser-Busch. Because of the public pressure, the Cardinals moved out of the Vinoy Park, and the Chamber of Commerce invited the black players to the breakfast. White declined the invitation.

Most of the rest of White’s book moves to New York City, where White joined Phil Rizzuto in calling Yankee games, and where he served five years as president of the National League.

His view of Vincent, under whom he served, and the baseball’s owners is gimlet-eyed. His take on the owners really did not change from his playing days.

“I realized early on that to them any individual player was just a piece of meat,” White wrote of his playing days. “They would keep you on as long as you were useful, but the minute you weren’t, you’d be gone — and it wouldn’t matter what you had done in the past, or if you had a sick child at home, or if you were broke and had nowhere to go.”

White’s book is a must-read for Cardinals fans, particularly those of a certain age. But his story of grit and integrity in the face of adversity deserves a much wider audience.