Book displays good and bad of life with plastics

Published 5:00 am Sunday, May 1, 2011

- Book displays good and bad of life with plastics

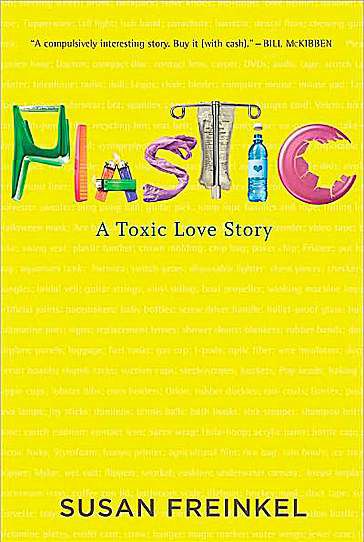

“Plastic: A Toxic Love Story” by Susan Freinkel (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 324 pgs., $27)

Not long ago, an irate reader e-mailed me, demanding to know whether I like plastic.

He was convinced that I didn’t, that I just wouldn’t admit it, and that all of this made me a bad person.

He further demonstrated his superiority in the matter by typing in the subject line, “wow u r really dumb.”

I barely knew how to respond. He might as well have asked if I liked gravity. Or the Pacific Ocean.

If ubiquity is a measure of affection, we all love plastic.

It’s everywhere, from our cars to our kitchens. It’s a mainstay in the medical profession. It brings us unbreakable toys and the modern marvel — the credit card.

The promise of plastic is “convenience and comfort, safety and security, fun and frivolity,” says author Susan Freinkel in her new book. But note the title: “Plastic: A Toxic Love Story.” Somehow, things have gone awry in Plasticville.

“Sure, plastics have been a good provider, but that beneficence comes with many costs that we never even considered in our initial infatuation,” she writes. “Plastics draw on finite fossil fuels. They persist in the environment. They’re suffused with harmful chemicals. They’re accumulating in landfills.”

Yet all the while, our dependence on plastic has continued to grow. In 1940, there was almost none. Today, the nation generates 600 billion pounds a year.

This is an important book, a thorough dissection of the complexities that today’s plastic world presents. More than that, it’s flat-out fascinating, each chapter more compelling than the last. Each page brings another eyebrow-raising fact or statistic, all of it eloquently told. Freinkel tells the story of plastics through the lens of eight common objects: comb, chair, Frisbee, IV bag, disposable lighter, grocery bag, soda bottle and credit card.

“Each offers an object lesson on what it means to live in Plasticville, enmeshed in a web of materials that are rightly considered both the miracle and the menace of modern life,” she writes.

As she points out, these simple objects “tell tangled stories.”

Perhaps nowhere has plastic achieved more for modern civilization than in the medical profession.

“With plastics, hospitals could shift from equipment that had to be laboriously sterilized to blister-packed disposables, which improved in-house safety, significantly lowered costs, and made it possible for more patients to be cared for at home.”

In telling the story of medical plastics, Freinkel visits a neonatal intensive care unit in Washington, where baby Amy, born four months early, is fighting for her life. She depends on plastic devices of every sort.

But as Freinkel watches the tiny girl struggle to breathe, she also thinks about how “research now suggests that the same bags and tubes that deliver medicines and nourishment to these most vulnerable children also deliver chemicals that could damage their health years from now.”

She’s speaking of phthalates and bisphenol A, which are hormone disrupters and are present in some plastics. Freinkel takes us to a huge vortex of plastic trash in the Pacific Ocean, formed by currents. She delves into the world of bioplastics and a Nebraska producer of plant-based plastics. She introduces us to Californian Mark Murray, who pushed for state legislation to ban plastic bags.

And who knew that among the Chester County, Pa., Wyeths was the inventor of the PET soda bottle? Nathaniel Wyeth, painter Andrew’s brother and a plastics engineer at DuPont for nearly 40 years, filed his patent for it in 1973. Today, about a third of the 224 billion beverage containers sold in the United States are made of PET.

But it’s also true that their growing presence as litter has helped rally and focus the nation’s recycling movement.

“We take natural substances created over millions of years, fashion them into products designed for a few minutes’ use, and then return them to the planet as litter that we’ve engineered to never go away,” Freinkel says.

“What will it take to turn that mindset around, to get people to value plastic for more than a one-night stand?”

In the final analysis, it’s not whether anyone likes plastic or not, but whether things are out of whack.

In the face of environmental ills, what are we to do once we’re finished with it? If additives are a problem, how can we get them out? And, in a future of decreasing supplies of oil, a base for many plastics, would we rather have transportation fuel or disposable cutlery?

In the final chapter, Freinkel takes us to a bridge over the Mullica River in South Jersey — made of nearly 1 million used milk jugs, with a few old car bumpers tossed in.

The builder noted that “all the negatives about plastic — that it lasts long and doesn’t degrade — are being turned into positives.”

Today, Freinkel says, “for better and for worse, we are in the plastics age. … Will archaeologists millennia from now scrape down to the stratum of our time and find it simply stuffed with immortal throwaways … evidence of a civilization that choked itself to death on trash?”