Like magic, great sports nicknames are slowly disappearing

Published 5:00 am Thursday, May 12, 2011

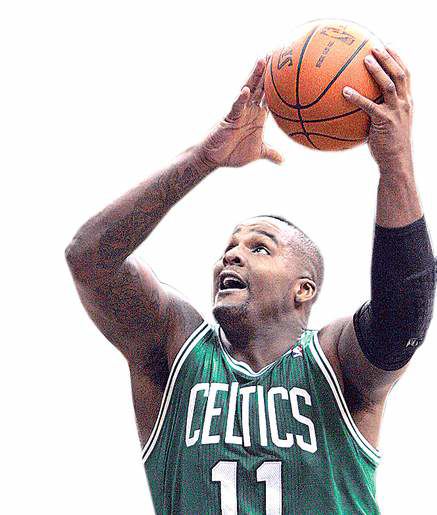

- Not many current players have a nickname like Boston's Glen 'Big Baby' Davis.

Today’s baseball rosters are filled with names, not nicknames, not like the ones that used to be.

The NBA playoffs are equally devoid of onomastic pleasures, just cheap echoes of Magic and the Mailman, Tiny and Tree, Chief and Cornbread. The NFL cannot match the treasured nicknames that evoke folk heroes like Night Train, Hacksaw and the Refrigerator.

A part of sports, somewhere near the soul, is slowly dying an unimaginative death. In an age of A-Rod and D-Wade, when nicknames rarely conjure imagery beyond a corporate logo, it can be easy to bemoan the loss of another slice of simpler times.

“There’s no substance there,” said Hall of Fame basketball player Walt Frazier, also known as Clyde.

But sociologists and experts in onomastics, the study of names, said the diminishment of nicknames is not exclusive to famous athletes. Studies on the subject are few, but there is widespread agreement that the use of nicknames across American society has steadily slipped.

“You just have to extrapolate in places where you can gather data, like baseball players,” said Cleveland Evans, an associate professor of psychology at Bellevue University in Nebraska, who writes a regular column on names for The Omaha World-Herald. “And they are certainly less common than they used to be.”

Less certain is why. Maybe it reflects a loss of intimacy and connectedness. Maybe it is because of the changing way we name children, or how we now deflect unflattering nicknames to shape our own identities. Maybe all the good nicknames are taken.

Whatever the case, the decline is most easily gauged in sports, where nicknames have long played a role in distinguishing and, at times, deifying athletes. They often arrived with a nickname given by family or school friends. (Such was the case for Lawrence Peter Berra, called Yogi by a boyhood friend for his apparent similarity to a film version of a Hindu yogi.)

Those who did not have a nickname were frequently given one by their teammates or coaches. (George Herman Ruth did not become Babe until he was signed by the Baltimore Orioles.)

Sports writers, looking for imagery or lyrical alliteration in the age before cable television, made a habit of bestowing nicknames on athletes too. Rams receiver Elroy Hirsch became Crazy Legs thanks to a Chicago newspaper reporter; decades later, a 15-year-old basketball player named Earvin Johnson was considered Magic by a reporter in Lansing, Mich.

“When we gave them a nickname, good or bad, it meant that we cared,” said Ernest Abel, a Wayne State professor of psychology and obstetrics who has studied names and is on the executive council of the American Name Society. “You don’t give someone about whom you are indifferent a nickname. The opposite of love is not hate; it’s indifference.”

Doc Rivers, coach of the NBA’s Boston Celtics, was simply Glenn as a boy in Chicago. But he was a big fan of Julius Erving, known as Dr. J, and wore an Erving shirt when he arrived to play at Marquette. Al McGuire, the former Marquette coach, was there and nonchalantly called him Doc.

“I didn’t have a lot of say-so in it,” Rivers recalled recently.

When Rivers played for the Atlanta Hawks in the mid-1980s, his teammates included Tree Rollins, Spud Webb and Dominique Wilkins, the Human Highlight Reel. Now Rivers coaches a perennial championship contender with big-name stars but nearly devoid of memorable nicknames. Shaquille O’Neal continually nicknames himself — generally a no-no — but he is more generally known as Shaq.

“Back then, I thought you got nicknamed from other people, and it stuck,” Rivers said. “And now it’s almost like guys or gym-shoe companies try to give you a nickname. It’s not as natural.”

One exception is Glen Davis, the soft-muscled Celtics forward. Everyone he knows — friends, coaches, his mother — has called him Big Baby since he was a big baby with a propensity for crying.

Now Davis is part of a dying legacy of great nicknames.

“That’s true,” he said. “Most people don’t even know my name. They just know Big Baby. That’s a good thing.”

Sociologist James Skipper, author of “Baseball Nicknames: A Dictionary of Origins and Meanings,” found that the use of nicknames peaked before 1920. It has since been in steady decline, dropping quickly in the 1950s.

Using a baseball encyclopedia listing all major league players from 1871 to 1968, Skipper found that 28.1 percent of players had nicknames not derived from their given names. (Lefty, Red and Doc were most popular.) No doubt the percentage has since dipped precipitously.

“The era of the colorful nickname may be over,” Skipper concluded about 30 years ago.

Chris Berman, the ESPN announcer, saw the void in the 1980s. He became known for his creation and use of hundreds of colorful nicknames, based mostly on puns — Mike (Pepperoni) Piazza, Sammy (Say it Ain’t) Sosa and Bert (Be Home) Blyleven among them.

“I viewed it as reviving a lost art,” Berman said. “Why aren’t there nicknames now? Maybe everything is so literal. You can see everybody on the Internet, TV, YouTube, whatever it is. There’s very little left to the imagination.”

Basketball’s Harlem Globetrotters, more than any other team, keep the nickname tradition alive. Every player on the roster has one.

“We want our fans to have an emotional attachment to our players, especially kids,” Kurt Schneider, the Globetrotters’ chief executive, wrote in an e-mail. “It’s more fun and easier to connect with — and emulate — Special K, Dizzy and Ant, than it is Kevin, Derick or Anthony. A nickname grants ethereal status to a player and elevates him to a platform where kids can aspire to be like them; it is a form of escapism and fantasy to want to be like Thunder or Hammer, and they are global in nature.”

In other words, the Globetrotters try to engineer a connection that generally does not exist today. Athletes are both more famous and more disconnected from fans than ever, sociologists have noted.

“I think it represents a loss of intimacy and identification with the players,” said Ed Lawson, past president of the American Name Society. “I don’t know how you have the same level of affection when a guy makes $16 million a year.”

But nicknames rarely came from fans; they came from friends and family, teammates and reporters. None of those connections are as strong as they once were.

“With the communication age, everybody’s on the computer, the cellphones, there’s not a lot of communication,” said Frazier, who became Clyde four decades ago when his wide-brimmed hats reminded New York Knicks teammates of the “Bonnie and Clyde” movie.

“When we traveled, there were only three channels, and all during the day there was nothing but soaps on,” Frazier added. “So the guys spent a lot of time together, playing cards, talking, hanging around in the same places, traveling together on the bus or whatever it might be. There was a lot of camaraderie among the players.”

George Gmelch, a professor of anthropology at the University of San Francisco and former minor league baseball player, said the influx of international athletes could be a factor in the decline of nicknames. U.S. players are less likely to give nicknames to Hispanic or Japanese players, he said.

He and others also suggested that nicknames are less useful, given the trend toward less-common names. After all, NBA player Joe Bryant was better known as Jellybean. His more famous son is simply Kobe.

According to the Social Security Administration, the 10 most popular baby names for boys in 1956 represented 31.1 percent of the total born. In 1986, around the time many of today’s athletes were born, the top 10 represented only 21.3 percent of the total.

“Nicknames are less needed today because given names themselves are so much more varied than they used to be,” said Evans, the Bellevue psychology professor.

He also posited that nicknames are often “humorous or noncomplimentary, and we may live in a culture where people are less willing to accept names that are less complimentary.”

It is telling that few of today’s biggest stars have widely used nicknames. LeBron James is an exception, but he is better known as LeBron than as King, the lofty nickname used for commercial purposes. Michael Jordan never really had a nickname, lest those who wanted to “be like Mike” be distracted from buying Air Jordans.

“Their own names now act as brand names,” said Frank Neussel, editor of Names: A Journal of Onomastics, and a University of Louisville professor of modern language and linguistics. “Your identity is not your nickname. It’s your stats.”