A former geek offers hope

Published 5:00 am Sunday, May 29, 2011

- A former geek offers hope

A few years ago I wrote an article about Rosie O’Donnell that made her mad. She told a gossip columnist I must have been “that nerdy Jewish kid in high school who ran the AV club.” The columnist called me for a reaction, and I had to correct O’Donnell. Actually, I was the president of the Herpetology Society.

“Ooh, herpetology!” says Alexandra Robbins, as we downed pancakes at the Crosby Street Hotel in SoHo, both of us seriously underdressed. “You mean, like, reptiles? That must have been interesting. Look what snakes did for Britney Spears.”

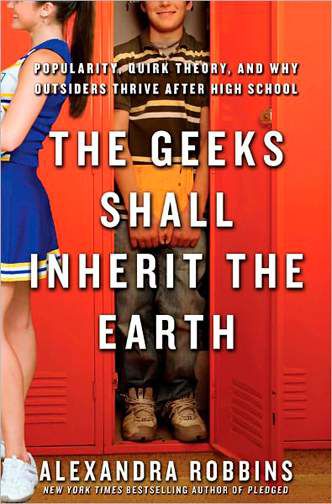

True, but I wasn’t tongue-kissing them on MTV. I just liked them a lot, and when I brought my boa, Julius Squeezer, to school with me, it wasn’t because I was goth. But my point — and Robbins’, in her latest book, “The Geeks Shall Inherit the Earth: Popularity, Quirk Theory and Why Outsiders Thrive After High School” (Hyperion) — is that I survived the teasing and lack of popularity to make a pretty good life. And so did she. And so, her book tells us, do many of the more interesting people on Earth.

At 34, Robbins looks not much older than the teenagers she writes about in books like “Pledged” and “The Overachievers”; her hair is pulled back in a no-nonsense ponytail and she is wearing minimal makeup, considering she just returned from a taping of “Today.”

Robbins has built her career giving voice and shape to the lives of teenagers — not the glossy simulacrums of Nick at Nite or the Disney Channel, but the living, breathing kind who worry not just about hair and shoes and romance (though there’s plenty of that), but about families, siblings, their futures. In her latest book, she follows the lives of high school archetypes — like the Loner, the New Girl, the Nerd and the Band Geek — plus one Popular Bitch, the Paris Hilton of her upstate New York high school.

Their stories beautifully demonstrate things we know intrinsically: that being popular is not always the same as being liked, that high school is more rigid and conformist than the military, and that the people who are excluded and bullied for their offbeat passions and refusal to conform are often the ones who are embraced and lauded for those very qualities in college and beyond — what Robbins has dubbed Quirk Theory.

School popularity

As anyone who’s seen movies like “Heathers” knows, the social agonies of high school are nothing new. But the Internet has magnified those feelings of alienation for the oddballs. Partly it’s the relentless exposure to celebrity culture, to images of perfection and roaring success with little discernible talent. (Hello, Kardashians.) But it goes beyond issues of appearance.

“Facebook is now the online cafeteria,” Robbins says. “It’s this public space, largely unsupervised, and it mirrors the cafeteria dynamic where you walk in and have to find a place to belong. At school, you have to pick a table. Well, on Facebook you not only have to pick a table, you have to pick who’s at your table and who’s not. And then kids feel they have to be publicists for themselves, maintaining their photos and status. It’s exhausting.”

Also exhausting is the care and feeding of popularity, which Robbins has discovered is not so much about being liked (some popular teenagers are liked, many are not) as about being known. “Popularity is a combination of visibility, influence and recognizability,” she says. “If you’re someone who engages in studying or practicing violin, these are not activities that put you in front of the student body. So these kids aren’t in the popular crowd, but it doesn’t say anything other than the fact that their talents are not visible.”

In other words, the president of the chess club may have more real friends than the cheerleader, but still be considered unpopular.

Robbins comes by her affinity for geeks honestly. She grew up in Bethesda, Md., in a family of teachers, an ultra-serious student, she says, in body suits, flannel shirts and Adidas slides with white socks.

She was a “floater,” one of those who didn’t have one set group of friends, but got along with many different kinds of people. At least, that’s what she thought until recently — when a former classmate wrote her a note, congratulating Robbins for how unrecognizable and good she looks now (“I was all, ‘Uh, thanks?’”) and apologizing profusely for how everyone made fun of her.

“I read her note and was like, ‘What?’ Because I didn’t know people made fun of me. And I liked this girl! I was on her soccer team.” Robbins let six months go by before she worked up the nerve to ask what her classmates had thought of her. The classmate wrote back: “Well, you were a dork … you were on the public speaking team, and in student government and on the newspaper. You had power and we didn’t. I guess I’d call you a power dork.”

“And I thought, ‘Well, OK: power dork. I’ll take it.’ Though I would have been mortified at the time.”

‘Power Dork’

The Power Dork made good, as many do. She first gained attention as an editorial assistant at The New Yorker where, in the course of researching her first book, “Secrets of the Tomb” (about the Skull and Bones secret society at her alma mater, Yale), she unearthed George Bush’s school transcript and SAT scores. The editors were so dubious that their lowly assistant had managed to do this that they sent the veteran political writer Jane Mayer in to check what she had found. Robbins proved correct, and Mayer became her mentor. Robbins, in turn, became Mayer’s sometime baby sitter.

Robbins met her husband, a lawyer for the military, while they were students at Yale. They bonded over their mutual love of “The Muppet Show” (she had a green Chevy Malibu named Kermit) and “Star Wars” — they walked the aisle to the “Star Wars” theme and still keep, in the foyer of their Washington-area home, a giant cardboard Yoda nailed to the wall in an elegant frame.

When not actively working on a book, Robbins has turned those hours she logged in her high school public speaking club into a lucrative lecturing career, and now tells anxious young people and their parents exactly how and why they should stop grade-grubbing and worrying about what parties they’re invited to.

At the end of a lecture I attended at School of the Future in Manhattan, there were teary questions from parents about their unpopular children, and there were kids who asked, in a variety of ways, “Will I be OK?”

Robbins has many deeply comforting words for these teenagers; and one story speaks in particular to those who’ve been right there with the high school outcasts. It’s about an experiment performed by the late-19th-century French naturalist Jean-Henri Fabre on caterpillars that were hard-wired to follow each other in a long head-to-tail line.

“Fabre set them up in such a way that they were following each other around the rim of a flowerpot — with their favorite food only inches away,” Robbins says. “For seven days they followed each other around until they died of starvation and exhaustion. They couldn’t see how a simple deviation from the path would get them to the food they needed right away.”

Geeks are many things, Robbins suggests. But one thing they aren’t are caterpillars.