Intestinal troubles

Published 5:00 am Thursday, July 7, 2011

- Intestinal troubles

Exercise is healthy, and it feels good, too. Except, of course, when accompanied by diarrhea or heartburn or intestinal bleeding.

Gastroesophageal reflux, diarrhea, cramping, nausea and gastrointestinal bleeding are common problems in endurance athletes, afflicting runners the most.

Moderate exercise tends to improve digestive functions in most people, according to Gayle Vanderford, a nurse practitioner in Bend Memorial Clinic’s gastroenterology department, but athletes engaged in particularly intense endurance activities are more likely to experience the aforementioned symptoms.

Blood in the stool, indicating bleeding from the intestines, is the least common of the ailments, Vanderford said. But if not addressed, it can, over time, lead to anemia.

“If you see blood in the stool, have it evaluated,” Vanderford said. However, “some athletes never see it.”

There are many factors, all of which are actors in the theater of gastrointenstinal distress.

Irritated intestines

The superior mesenteric artery, a branch off of the aorta, supplies oxygen-rich blood to the intestines. When athletes are engaged in intense endurance sports, their blood flow is diverted to the working muscles: legs, heart, lungs. Blood flow to the intestines — and therefore oxygen and nutrient flow — can drop as much as 80 percent, said Vanderford and Dr. Lauren Simon, who specializes in sports medicine at the Loma Linda University Medical Center.

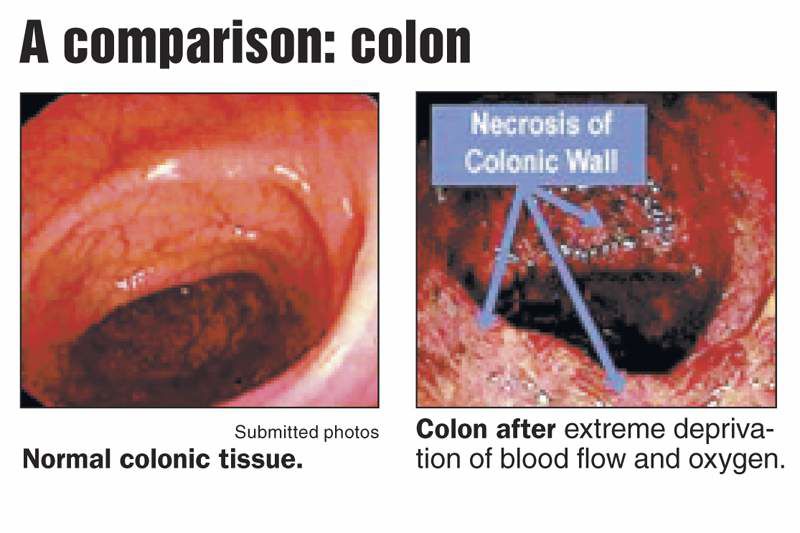

Reduced blood flow creates irritation in the large intestine, also known as the colon. That irritation can cause tissue there to slough off and bleed, Vanderford said.

In only the most rare and severe scenarios does part of the gut die after a prolonged loss of blood flow. In those cases, the athlete might have parts of the lower intestine surgically removed. In most cases, the gut is forgiving and can heal.

Many kinds of athletes, including cyclists or nordic skiers, can lose blood flow to their gut during intense workouts, but the pounding and jarring nature of running is believed to increase the irritation.

Dehydration can be another factor that adds to gastrointestinal distress. Dehydration can cause fluids to shift out of the intestines, increasing irritability and sloughing or bleeding. Dehydration is more likely to cause cramping or bleeding than diarrhea, Vanderford said.

The precise causes of diarrhea in endurance athletes is not well understood and hasn’t been clinically studied much. Simon said she expects to see more data in the future.

Simon suspects that diarrhea is related to the intestinal irritation, which can impair the intestinal organ’s barriers. When the barrier is damaged, it gets ulcerated and charred-looking. In that state, she said, the wrong kinds of bacteria can infect the digestive system. A bacterial imbalance could play a role in diarrhea.

Hormonal changes resulting from a nervous system response to intense exercise might also be a factor, Simon said.

Sports energy food

Many athletes consume high-carbohydrate energy gels because they digest more quickly than bulkier food. Sports nutrition offers instant energy after an athlete’s energy stores get depleted, generally after about an hour of endurance exercise. For some people, the sports nutrition products are tough on the gut. But each body reacts in its own way. Some people can tolerate only specific brands of gels. To know what works for them, endurance athletes need to experiment.

The high-carbohydrate energy products can trigger rapid fluid shifts into the intestines. The body naturally wants to dilute those high-carbohydrate loads, Vanderford said. That could trigger diarrhea, she said, also known as “runner’s trots.”

Simon has, as research, taken pictures at the lines in front of the porta-potties along marathon routes.

“In higher-mileage areas, there were more people going because of getting runner’s diarrhea,” she said.

People blame high-carbohydrate energy products for all kinds of gastrointestinal discomfort, Simon said.

Bend runner Connie Austin, creator of and coach for the Learn to Run program, said when she consumed gels and electrolyte replacement drinks, she got diarrhea and cramps even though she drank water, too. She has since started using real food, such as an oat-and-honey granola bar.

Ashleigh Mitchell, of Bend, who operates a Pilates and Movement Therapy business, said she tried a new energy fuel during a training run for a half-marathon last year and ended up throwing up throughout the entire run as a result.

Normally, she would eat toast with peanut butter and banana before a run and then drink plain water on the trail. But going into a long training run, she was nervous that she wouldn’t have enough energy, so she put an electrolyte powder in her water.

“I tried it and within 3 miles it wasn’t sitting well. Without being graphic, between mile 3 and 13.1, about every minute I needed to stop and vomit on the side of the trail,” she said. For the race, she went back to her real-food and water routine and did fine. She’s since experimented with different products and discovered a tolerable electrolyte chew that digests easier than peanut butter and doesn’t make her sick.

Digestion

When the body is focused on exercise, the stomach and intestines don’t process and move food. And, if things aren’t moving through the lower digestive system, they might back up into the higher parts of the digestive system and create reflux, or heartburn.

“If the colon is not doing its job, the body says, ‘Don’t bring anything else down here,’” Simon said.

Reflux at some point affects about 60 percent of athletes, including runners, cyclists, weight lifters, football players and others who increase the pressure in their abdomens. Exercise also can weaken the seal of the lower esophageal sphincter, Vanderford said, which is the valve between the esophagus and the stomach. That allows stomach acids to rise back up into the esophagus, creating heartburn.

Studies show that gastrointestinal symptoms in runners are more likely to occur in the lower intestine, such as diarrhea and bleeding. Cyclists are more likely to experience upper gastrointestinal problems such as reflux. Perhaps it’s body position, Simon said.

Symptoms tend to worsen with increased training or particularly strenuous workouts and races.

Prevention

“All these things are less likely to happen with a good training program,” Vanderford said. “Research says it’s less likely to happen to better-trained athletes.”

Training up to a race or a hard workout builds strength in all parts of the body — not just the leg muscles, for example, but the whole vascular system that is involved. A better-trained athlete’s entire system has more capacity for the intensity of a particularly long and hard run, she said.

The muscles are more experienced and efficient at using oxygen from the blood, so they don’t need as much blood flow, Vanderford said.

So a well-trained runner, for example, won’t have as dramatic a blood shift out of the intestines during a race, according to an article in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine in 2009. The article offers a case study about a 31-year-old man who collapsed at the end of the London marathon and was taken to the emergency room. During the marathon he got abdominal cramps and rectal bleeding. He ended up with surgery that removed part of his large intestine.

He had previously exercised occasionally but only trained in distance running for six weeks prior to the marathon. That’s about one third of the time most people train for marathons. He had never run more than 14 miles.

Older runners are less likely to have problems too, probably because they have grown more knowledgeable about diet and hydration, Vanderford said.

She and other medical experts say reducing training intensity or distance can alleviate most symptoms. The gut is very forgiving, Simon said, and in most cases will heal quickly.

Everyone has a different breaking point at which their gut stops working properly, Simon said. For some people it might be six miles, for others it’s an ultra marathon. When working with clients, she said, “it should be safety first, and then, are you having fun?”

“If you’re passing blood or diarrhea, that’s usually a signal that maybe (the runner) should change something,” she said. “Fortunately many people self-stop.”

For those who can’t stop, she suggests working with a sports dietitian and changing the training regimen. Perhaps a runner should substitute more cycling, or nordic skiing. “I would not say ‘You can’t exercise.’”

Vanderford, a distance runner, said people always ask her why she puts herself through such grueling distances. And although she’ll admit that running isn’t always good for you, “There’s a certain mindset amongst runners. It’s a challenge and I couldn’t really explain what makes me still run. Certain people just love to run. You feel so good when you run.”

Graphic by Andy Zeigert The Bulletin

Graphic by Andy Zeigert The Bulletin

More common in runners

The incidence of gastrointestinal problems such as reflux, abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody diarrhea and nausea are found in up to 81 percent of high-endurance athletes, most commonly runners and to a lesser extent cyclists and swimmers.

Blood can appear in the stool of:

• 20 percent of runners after a marathon.

• 87 percent of runners following an ultramarathon.

Source: Handbook of Sports Medicine by Wade Lillegard and Karen Ruckerthe

Prevention tips

To reduce incidence of gastrointestinal disorders, athletes should try the following:

• Start by lowering the intensity level of exercise and then gradually increase activity.

• Void and defecate before exercise.

• Avoid intense exercise within three hours of a meal.

• Avoid high-fiber or high-fat foods before exercise.

• Limit caffeine for one to two hours before exercise.

• Stay hydrated.

Source: Dr. Lauren Simon, who specializes in sports medicine at Loma Linda University Medical Center, and the American College of Sports Medicine