‘Baby Einstein’ creators say study was flawed

Published 5:00 am Friday, July 15, 2011

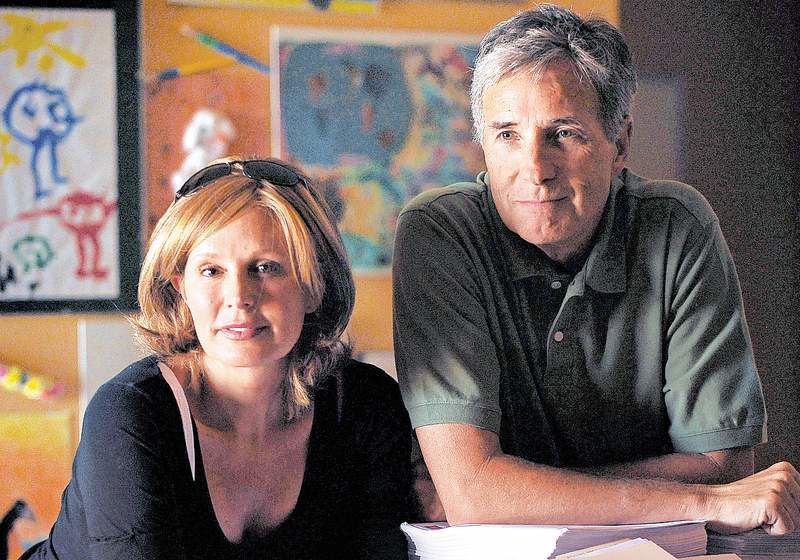

- Bill Clark and Julie Aigner-Clark created “Baby Einstein,” the billion-selling musical videos that exposed babies to Mozart and sock puppet reindeer. In 2007, the University of Washington published a widely distributed study saying those videos actually harmed verbal development. The Clarks launched a four-year battle to debunk the study. William Clark is convinced that documents he obtained through a lawsuit prove the research was flawed and unfairly characterized their products.

DENVER — Four years, one lawsuit and relentless pestering after a university study slammed their iconic Baby Einstein videos as harmful, a Denver couple has forced the University of Washington to turn over original research documents that they say confirm what they always suspected: The study was deeply flawed and unfairly characterized their products.

The university also has paid $175,000 toward the legal fees of the couple, Bill Clark and Julie Aigner-Clark.

Trending

To Bill Clark, the files turned over by the university demonstrate “troubling aspects of how it was conceived, funded and publicized.”

But UW spokesman Bob Roseth said the university stands behind the research and its findings, as well as how those findings were portrayed.

Julie Aigner-Clark, a former English teacher, conceived the Baby Einstein videos, which combined classical music, verse, puppets and shiny objects. The couple, who live outside Denver, shot the first video, “Baby Mozart,” in their basement. It was released it in 1996.

The Clarks have described the videos as “engaging ways to expose babies and their parents to the arts and nature.”

But for millions of new parents, they also provided 30 minutes to grab a shower or a sandwich with minimum guilt. By the time the Clarks sold “Baby Einstein” to Disney in 2001, sales had climbed to more than $17 million.

Then in 2007, the Journal of Pediatrics published a study by three UW researchers: Frederick Zimmerman, Dimitri Christakis and Andrew Meltzoff.

Trending

The study reported that among babies between the ages of 8 and 16 months, every hour spent daily watching videos such as “Brainy Baby” or “Baby Einstein” translated into six to eight fewer words in their vocabularies compared to other children their age.

“This analysis reveals a large negative association between viewing of baby DVDs/videos and vocabulary acquisition in children ages 8 to 16 months,” the article stated. It added that no other media had any effect, for better or worse.

But included in the materials turned over to Clark are exchanges in which the university’s Institutional Review Board scolded Zimmerman for changing the study without notifying anyone, or getting approval. The board at one point directed him to re-survey participating parents, but later backed off that requirement.

In his response, Zimmerman said the original study, which was to have involved more subjects and included follow-up over a period of months, proved too costly.

More importantly, from the Clarks’ perspective, is correspondence showing the concern of one researcher about how results were analyzed.

While children 8 months to 16 months who watched baby videos fell behind in vocabulary, the study also found that in children aged 17 to 24 months, vocabulary increased, and the negative effects evaporated.

In an e-mail to Zimmerman, co-author Andrew Meltzoff asked, “What’s the notion about how (we’re) reconciling the fact that there was an effect on the young kids but it washed out by the time they were 17-24, and we now will be wanting to follow the young kids when they’re older?”

Zimmerman responded that he hoped to do a follow-up survey with the same parents.

“This has been a great project and it will be a huge payoff in terms of high profile research and promising new research directions,” he wrote Meltzoff.

The vocabulary rebound was part of the published report, but was downplayed in press releases distributed by the university and Seattle Children’s Hospital, where Christakis is on staff.

The researchers, especially Christakis, whose website describes him as “an international expert on children and media,” told reporters around the country that not only were the videos not going to produce “Baby Einsteins,” they might actually harm children.

Around the country and beyond, headlines screamed that far from cultivating intelligence, “Baby Einstein” videos would make children dumber. The Los Angeles Times wrote, “Parents hoping to raise baby Einsteins by using infant educational videos instead might be creating baby Homer Simpsons.”

The Disney Co., which saw its investment in Baby Einstein potentially swirling the drain, tried to control the damage. In a letter to Mark Emmert, then-president of the University of Washington, Disney chief Robert Iger called the university’s releases “misleading, irresponsible and derogatory” and demanded a retraction.

But the effort didn’t accomplish much, and fallout from the study endured. The Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood asked the FCC to fine Disney for making false claims about Baby Einstein’s benefits. By the fall of 2009, Disney was offering refunds to dissatisfied customers.

As that was unfolding, Bill Clark was simmering.

He contacted the university, demanding the research documents that produced the study findings. When he perceived the university was dragging its feet in complying, he got madder.

At one point, Zimmerman assured a university administrator that the entire brouhaha “will just blow over.”

It might have, were it not for a 2009 article in the United Kingdom’s The Guardian newspaper. The article convinced Clark that the negative press wouldn’t go away.

So he redoubled his effort.

Now that he has the documents, Clark wants the National Science Foundation and other research oversight groups to look into the UW team’s actions.