Classroom is futuristic; test scores are stagnant

Published 5:00 am Monday, September 5, 2011

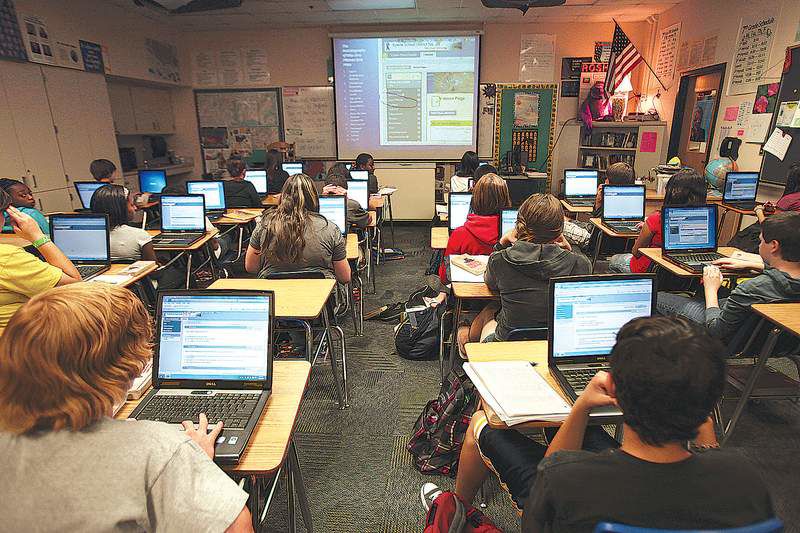

- Students use laptops to take their final exam last spring at Kyrene Aprende Middle School in Tempe, Ariz. Schools are embracing digital learning, but evidence is scarce that the expensive technology is improving educational outcomes.

CHANDLER, Ariz. — Amy Furman, a seventh-grade English teacher here, roams among 31 students sitting at their desks or in clumps on the floor. They’re studying Shakespeare’s “As You Like It” — but not in any traditional way.

In this technology-centric classroom, students are bent over laptops, some blogging or building Facebook pages from the perspective of Shakespeare’s characters. One student compiles a song list from the Internet, picking a tune by the rapper Kanye West to express the emotions of Shakespeare’s lovelorn Silvius.

The class, and the Kyrene School District as a whole, offer what some see as a utopian vision of education’s future. Classrooms are decked out with laptops, big interactive screens and software that drills students on every basic subject. Under a ballot initiative approved in 2005, the district has invested roughly $33 million in such technologies.

The digital push here aims to go far beyond gadgets to transform the very nature of the classroom, turning the teacher into a guide instead of a lecturer, wandering among students who learn at their own pace on Internet-connected devices.

“This is such a dynamic class,” Furman says of her 21st-century classroom. “I really hope it works.”

Hope and enthusiasm are soaring here. But not test scores.

Since 2005, scores in reading and math have stagnated in Kyrene, even as statewide scores have risen.

To be sure, test scores can go up or down for many reasons. But to many education experts, something is not adding up — here and across the country. In a nutshell: Schools are spending billions on technology, even as they cut budgets and lay off teachers, with little proof that this approach is improving basic learning.

At the same time, the district’s use of technology has earned it widespread praise. It is upheld as a model of success by the National School Boards Association, which in 2008 organized a visit by 100 educators from 17 states who came to see how the district was innovating.

And the district has banked its future and reputation on technology. Kyrene, which serves 18,000 kindergarten to eighth-grade students, mostly from the cities of Tempe, Phoenix and Chandler, uses its computer-centric classes as a way to attract children from around the region, shoring up enrollment as its local student population shrinks. More students mean more state dollars. And the push for technology is to the benefit of one group: technology companies.

The issue of tech investment will reach a critical point in November. The district plans to go back to local voters for approval of $46.3 million more in taxes over seven years to allow it to keep investing in technology. That represents around 3.5 percent of the district’s annual spending, five times what it spends on textbooks.

A dearth of proof

The pressure to push technology into the classroom without proof of its value has deep roots.

In 1997, a science and technology committee assembled by President Bill Clinton issued an urgent call about the need to equip schools with technology.

If such spending was not increased by billions of dollars, American competitiveness could suffer, according to the committee, whose members included educators like Charles Vest, then president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and business executives like John Young, the former chief executive of Hewlett-Packard.

To support its conclusion, the committee’s report cited the successes of individual schools that embraced computers and saw test scores rise or dropout rates fall. But while acknowledging that the research on technology’s impact was inadequate, the committee urged schools to adopt it anyhow.

Kyrene had the same sense of urgency as Clinton’s committee when, in November 2005, it asked voters for an initial $46.3 million for laptops, classroom projectors, networking gear and other technology for teachers and administrators.

Before that, the district had given 300 elementary school teachers five laptops each. Students and teachers used them with great enthusiasm, said Mark Share, the district’s 64-year-old director of technology, a white-bearded former teacher from New York with an iPhone clipped to his belt.

“If we know something works, why wait?” Share told The Arizona Republic the month before the vote. The district’s pitch was based not on the idea that test scores would rise, but that technology represented the future.

The measure, which faced no organized opposition, passed overwhelmingly. It means that property owners in the dry, sprawling flatlands here, who live in apartment complexes, cookie-cutter suburban homes and salmon-hued mini-mansions, pay on average $75 more a year in taxes, depending on the assessed value of their homes, according to the district.

But the proof sought by Clinton’s committee remains elusive even today, though researchers have been seeking answers.

Many studies have found that technology has helped individual classrooms, schools or districts. But often smaller studies produce conflicting results. Some classroom studies show that math scores rise among students using instructional software, while others show that scores actually fall. The high-level analyses that sum up these various studies, not surprisingly, give researchers pause about whether big investments in technology make sense.

A review by the Education Department in 2009 of research on online courses — which more than 1 million K-12 students are taking — found that few rigorous studies had been done and that policymakers “lack scientific evidence” of their effectiveness. A division of the Education Department that rates classroom curriculums has found that much educational software is not an improvement over textbooks.