Walter Bonatti, daring mountaineer, dies at 81

Published 5:00 am Saturday, September 17, 2011

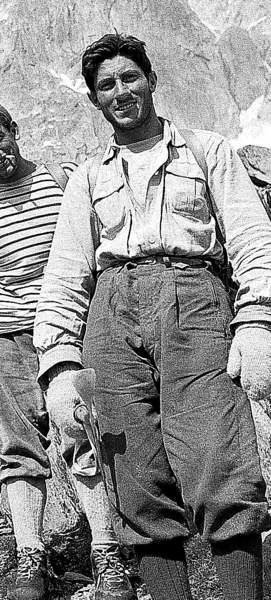

- Italian climber Walter Bonatti, who was among the first team to ascend K2, has died. He was 81. He is pictured here on Mount Blanc in 1955.

Walter Bonatti, one of the world’s greatest mountaineers, who pioneered some of the most difficult and breathtaking climbs on the earth’s tallest mountains, often alone, died Tuesday in Rome. He was 81.

His death, at Gemelli Hospital, was confirmed by his partner, Rossella Podesta, and Umberto Martini, president of the Italian Alpine Club. No cause was given.

Bonatti was a member of the Italian team that conquered K2 in northern Pakistan, the world’s second-tallest mountain, on July 31, 1954. The ascent was a moment of glory for Italy, coming in the aftermath of its defeat in World War II and at a time of fierce international competition to lay claim to the Himalayas.

But the achievement was tarnished by bitter controversy. Bonatti, at 24 the youngest member of the expedition, did not reach the summit and later accused two colleagues of denying him an opportunity to share the moment.

As he recounted the episode, he and a Hunza porter were carrying oxygen tanks to the highest camp, at 26,000 feet, to help the team in its final push. But the camp was not where they had expected to find it — concealed by the other two, he maintained — and Bonatti and the porter, Amir Mahdi, were forced to spend a terrifying night out in the open.

They barely survived. In the morning, Mahdi descended in a headlong rush, almost out of his mind, losing fingers and toes to frostbite afterward.

A few hours later, the other two men, Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli, emerged to retrieve the oxygen tanks that Bonatti and Mahdi had left in the snow and went on to reach the summit around 6 p.m.

The Italian climbing establishment sided with Compagnoni and Lacedelli, but the dispute left a bitter taste in the Italian climbing world and remained a subject of argument for the next 50 years.

“The K2 story was a big thorn in his heart,” Podesta, 77, said in a telephone interview Thursday while she and family members were taking Bonatti’s body from Rome to their home in Dubino, a village north of his birthplace, Bergamo, in northern Italy. “He could not believe that, even after all those many years, nobody had apologized or acknowledged the truth. This falseness has left a mark in his life.”

Bonatti became known as an angry loner who shied away from the bigger expeditions to take on new routes and new peaks his own way, sometimes at great risk.

“Bonatti was just a boy from Bergamo who in a very few years became the best climber in the world,” the mountaineer Reinhold Messner told the Italian newspaper La Repubblica on Thursday. Bonatti, he added, had been envied around the world because he was “too ahead of the curve, too alone, too good.”

David Roberts, a journalist who writes about mountaineering, said of Bonatti in an interview Wednesday: “If you had a poll of the greatest mountaineers of all time, he might win it. It is that simple.”

“Everything he did,” he added, “was out there pushing a new frontier that no one else dared push.”

Probably Bonatti’s greatest accomplishment came in 1955, when he took an untried route to make a solo ascent of the west face of the Petit Dru, a huge granite pinnacle hanging over Chamonix in the French Alps. A daunting section of rock he scaled there became known as the Bonatti Pillar.

Seven years later, alone in a Swiss Alps winter, he climbed a new route up the middle of the Matterhorn’s north face. That was to be his last great climb, Roberts said. At 35, Bonatti more or less quit climbing to write books about mountaineering and work as a writer and photojournalist for magazines like Epoca in Brazil.

Besides Podesta, his partner, Bonatti’s survivors include two stepsons from her previous marriage and nine step-grandchildren. Bonatti had also been divorced.

He was born on June 22, 1930. In his later years he was a celebrated and honored adventurer who chronicled his career in an autobiography, “The Mountains of My Life.”