Fall books

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 25, 2011

- Fall books

It’s tempting, looking at this fall’s books, to think of this as a political season. Dick Cheney got it started with “In My Time: A Personal and Political Memoir,” and in November we’ll see a different take when Condoleezza Rice publishes “No Higher Honor: A Memoir of My Years in Washington.” John Paul Stevens reflects on his 35 years on the Supreme Court in “Five Chiefs: A Supreme Court Memoir”; Michele Bachmann weighs in with an as-yet-untitled book about her life.

Still, for all that, the biggest books this fall are works of fiction — in terms of not just anticipation but also size. Haruki Murakami’s much-anticipated novel “1Q84,” which unfolds in an alternate universe (or does it?), weighs in at 932 pages; Peter Nadas’ Hungarian epic “Parallel Stories” spans 1,133.

In “Reamde,” science fiction visionary Neal Stephenson takes 981 pages to spin a saga of technological intrigue and online fantasy, while Stephen King’s 800-plus-page “11/22/63” reimagines the Kennedy assassination through the filter of a time traveler intent on correcting the wrongs of the past.

Rounding out the epics is Chad Harbach’s 500-page debut, “The Art of Fielding,” a baseball novel set at a small Midwestern college, revolving around the lives of five friends.

Not all the fall’s fiction is so massive: National Book Award winner Denis Johnson’s novella “Train Dreams” is a nuanced portrait of a day laborer in an earlier America and the quiet stoicism that becomes his code.

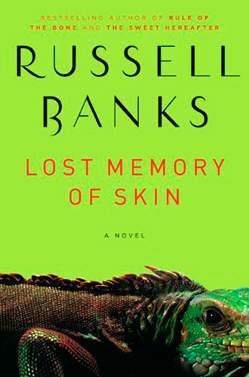

Don DeLillo publishes his first book of short fiction, “The Angel Esmeralda,” featuring nine stories dating to the late 1970s. Russell Banks’ “Lost Memory of Skin” explores a different sort of desperation, built around a young man on probation for indiscretions with an underage girl.

“The Marriage Plot,” Jeffrey Eugenides’ follow-up to his Pulitzer Prize-winning “Middlesex,” goes back to the 1980s, evoking college life and deconstructing love; Lydia Millet’s “Ghost Lights” is a sequel to her 2008 novel “How the Dead Dream.” In “Zone One,” Colson Whitehead puts a literary spin on the zombie genre, while the eight stories in Elissa Schappell’s “Blueprints for Building Better Girls” connect in unexpected ways in exploring how contemporary women live.

Beyond politics, perhaps the most eagerly awaited nonfiction book of fall is Joan Didion’s “Blue Nights,” which picks up where “The Year of Magical Thinking” left off to examine the death of her daughter Quintana and her reactions to growing older. Christopher Hitchens’ “Arguably” gathers more than 100 essays on world affairs, literature and the vicissitudes of the author’s mind.

In “Quite Enough of Calvin Trillin,” the New Yorker contributor offers 40 years of humor writing, pretty much the same span covered by “Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone: The Essential Writing of Hunter S. Thompson,” which includes “Fear and Loathing in Elko,” the gonzo journalist’s 1992 takedown of Clarence Thomas, and “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan,” his iconic piece on the 1970 killing of former Los Angeles Times columnist Ruben Salazar.

In “The Ecstasy of Influence,” Jonathan Lethem mixes old and new essays to frame a kaleidoscopic look at what it means to be a writer and a thinker; Lawrence Weschler does something similar with “Uncanny Valley: Adventures in the Narrative,” which brings together occasional pieces, criticism and profiles.

Dubravka Ugresic’s “Karaoke Culture” investigates the decentering influence of pop culture, while John Jeremiah Sullivan’s “Pulphead” collects essays from GQ, the Paris Review and elsewhere to get at what Greil Marcus once called “the old, weird America.” And speaking of the old, weird America, don’t forget Julia Scheeres’ “A Thousand Lives,” which tells the tragic tale of Jonestown — in its way, a peculiarly American apocalypse.

What’s left? L.A. expatriate David Trinidad’s “Dear Prudence: New and Selected Poems” looks at the career of an essential poet, going back to the 1970s; Patti Smith’s collection of impressionist prose pieces, “Woolgathering,” originally published in 1992 by Hanuman Books, appears in a trade edition for the first time. Art Spiegelman proves you can go home again in “Metamaus,” a deconstruction of his graphic novel about the Holocaust, while Matt Kish brings a related sensibility to “Moby-Dick in Pictures,” in which he literally draws over Herman Melville’s novel page by page.

But given where we started, perhaps it’s most appropriate to end with “The Annotated Peter Pan,” edited by Harvard professor Maria Tatar, in which the boy who never grew up finds himself redefined for a new generation: the very mission of a living literature, political or otherwise.