Missed meds cost a lot

Published 5:00 am Thursday, October 13, 2011

- Missed meds cost a lot

Uninsured and unable to work, Karl Severson’s monthly costs for a critical anti-clotting medication were becoming a significant problem. Despite years of trying to find a solution to persistent atrial fibrillation, the 60-year-old Redmond man was considering abandoning the Coumadin his doctor had prescribed and switching to aspirin.

It wasn’t so much the cost of the drug as all of the additional monitoring required to make sure the clotting tendency of his blood remained within the proper range.

“When you’re on Coumadin, they have to check your blood. It’s like $60 a pop some places. Some places it’s as high as $85,” Severson explained. “If you imagine doing that at a minimum every three weeks — and if the numbers are off, then you’ve got to do it once a week — that’s really cost prohibitive.”

Then a year and a half ago, he learned about Mosaic Medical in Bend, which would charge him on a sliding scale based on his income. Coumadin monitoring at the clinic now costs him only $28 a visit.

“Sometimes I have to scrape a little bit to make it,” he said.

“But I really appreciate that because I don’t know what I would do if Mosaic wasn’t there.”

Millions of patients in the U.S. have found themselves in similar situations, facing decisions about whether to take their medications as prescribed by their doctors. Studies show that up to half of all Americans don’t.

According to recent estimates, that could be costing the health care system anywhere from $30 billion to $290 billion a year.

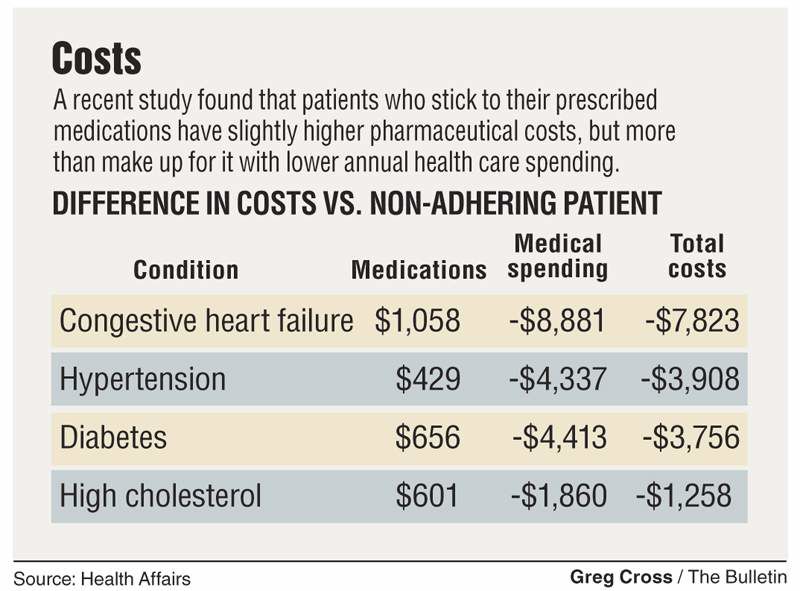

A study published in Health Affairs earlier this year calculated that patients with chronic conditions who slack off on taking their prescribed medications account for an additional $7,800 per year in health care spending. Nonadherence is blamed for 10 percent of hospital visits and 23 percent of nursing home admissions.

“There’s definitely been a more recent interest in medication adherence. If patient took their medications appropriately they wouldn’t go to the ER as much, they wouldn’t be admitted to the hospital for management of their chronic conditions.” said Josh Bishop, a pharmacist with PacificSource Health Plans in Bend.

“The data shows that when you increase pharmacy costs, you save a lot of medical costs.”

Yet physicians often have few resources to help track medication adherence. New payment approaches that reward doctors for managing a patient’s care may soon change that and ask doctors to become much more vigilant about keeping patients on track with their medications.

Black hole

When doctors prescribe new medications they usually tell patients why they need the drugs, describe the potential side effects or drug interactions and leave the exam room assuming the patient will take the drug as recommended. But in reality, they have no way of knowing whether the patient will even fill the prescription, much less take all the pills on time.

“It’s really one of the great weaknesses of our health system in terms of not being able to follow up,” said Dr. Sean Rogers, medical director at Bend Memorial Clinic. “Right now nobody has that info. If I write a prescription and I send it to the pharmacy, and the patient never goes and picks that up, nobody knows that.”

While financial difficulties are often the main culprit, there are plenty of other reasons patients don’t take their medications. Some abandon their drug therapies once they start feeling better. Others are simply forgetful or don’t understand the risks of not keeping up with their drugs.

Kyle Wills, a pharmacist at BMC, recently met with a patient who purchased all her medications from Canadian pharmacies to lower her costs. But she became confused about the different brand names on the Canadian products and simply stopped taking her drugs. Another patient had trouble remembering whether she had taken her drugs on a given day, so Mills and a case manager got her a weekly pill box and showed her how to fill it.

Sometimes solutions can be that simple. But other times, it can be difficult for providers to know what’s really keeping patients from staying on top of the medications.

“Often times it’s the volume,” said Dr. Bruce McLellan, a cardiologist with Heart Center Cardiology in Bend.

Patients might be taking four or five medications after heart failure or a heart attack. They may also be taking a blood pressure or cholesterol medication, and perhaps medications to control their diabetes.

“Somebody could be taking 10 to 15 medications,” he said.

And studies show the more drugs a patient takes, the less likely he or she is to take all of them as prescribed. McLellan said patients also stop taking drugs because of concerns about real or perceived side effects.

“So they stop taking the medication but they never said anything,” he said. “Now it’s three months, six months, sometimes a year later when you’re having an annual visit, and they’re feeling kind of sheepish that they stopped the medicine 10 months ago but they never told anyone.”

A cardiologist may suspect a patient has stopped taking his medication when his blood pressure or cholesterol suddenly rises. If a patient gets a blood clot after getting a stent placed, chances are the patient has stopped taking his anti-clotting drug. But in most cases, unless the patient volunteers that information, it can be hard to come by.

“I’ve been impressed that a lot of patients are really forthcoming and they will tell,” McLellan said. “But you have to assume there are one or two who are not telling you directly.”

Data points

Health plans often do know the adherence habits of their members, but so far few have been using that data to help physicians improve patient outcomes. Insurers calculate medication possession ratios for members based on the percentage of the prescriptions filled at pharmacies and billed to the plan. If a patient was given a six month prescription but has filled it for only three months worth of drugs, that’s a possession ratio of 0.5.

“Under the industry standard, which is supported by evidence-based medicine, 0.8 is the acceptable medication possession ratio for someone with a chronic condition,” Bishop said.

PacificSource monitors when patients fall below that ratio and try to intervene by calling the patient to determine the problem.

PacificSource has also made that information available to clinics. When Wills, the BMC pharmacist, meets with PacificSource patients to review their medications, he can call the health plan and get the patient’s possession ratio. The objective data helps him identify where patients may be facing barriers.

Bishop said the plan has been trying to get physicians to use that data to improve care as well, but often gets “push-back” from doctors.

“They’re not sure what to do with that data,” he said. “It’s a patient motivation issue.”

Dr. Meghan Brecke, a physician with St. Charles Family Care in Bend, said doctors constantly worry about whether patients will take their medications and try to establish good communication with patients to address any potential hurdles.

“The single most important point for us is making sure that we’re having an honest conversation so that patient feels comfortable letting us now if there’s some barrier,” she said. “We can find a way to make a medication regimen more manageable for patients, but we need to know what the barriers are and why it’s an issue for them.”

Targeted approach

There may not be a one-size-fits-all solution. Cynthia Russell, a nursing professor at the University of Missouri, studied medication adherence in kidney transplant patients who must keep to a strict schedule of immunosuppressant drugs to keep their bodies from rejecting the donated organs.

“If there is a rejection happening, they need to go to the hospital and get steroid therapy and that typically costs $5,000 to $7,000,” Russell said. “So obviously if you can keep them on their medications and avoid hospitalizations for rejections, those are ways you can really save a lot of money.”

Transplant patients might represent an extreme case. It’s hard to imagine that someone who experienced kidney failure and received a transplant wouldn’t be hypervigilant about taking medications that protect the new kidney. That’s precisely why Russell chose to study that group.

“It’s just the fact that medication taking is a behavior and we are all human,” she said. “Doing something repetitively every morning and every evening for years and years and years is just difficult. We all make mistakes.”

What’s clear is that the standard approach of educating patients about their drugs, how to take them and what side effects to expect isn’t working.

“If education made a difference in behavior, all of the health care providers would be perfect on their behaviors with smoking, alcohol, and sun protection, and we know that’s not the case,” Russell said. “When people are having trouble taking their medications, providing additional education is really a waste of time.”

Russell used special pill bottles with cap that recorded when the bottles were opened. Nurses then reviewed the data with patients, showing them a computer print out of when they took their medications. But the nurses then took it one step further, talking with patients about how they could integrate their medications into their daily routines.

For one patient, that meant putting his pills next to the coffee maker so he would remember to take them each morning. (Caffeine addicts can attest that nobody forgets their morning coffee.) Another kept his medications in his car, as he was always in the middle of a one-hour commute when it was time to take them. Others kept their medications by the TV remote to avoid missing their evening doses.

“They don’t have to remember. The meds are right there in plain sight and right around doing something else that they’re doing,” Russell said. “It’s almost like muscle memory. You don’t need to think about it. It becomes so routine.”

Such interventions, however, are resource intensive. They require nurses or case managers who can monitor patients’ medication adherence and then find ways to integrate pill taking into daily routines. The electronic pill caps, she said, cost about $120 each, and insurance companies generally won’t cover the additional costs despite the potential for savings.

“If you think about those in terms of preventing a rejection, it’s enormous,” Russell said.

Russell and her colleagues are now hoping to conduct additional research to see if the short term use of monitoring caps can help establish long term adherence. They could then be used to intervene with patients at higher risk of missing their meds.

The challenge for providers, however, is how to identify such patients before they experience a costly and potentially devastating medical crisis. Adolescents are often at risk as they start to assert their own independence and take personal responsibility for taking their medications. And older individuals with cognitive impairment are also at higher risk, although researchers are still unclear about where to set the cut-off point where someone can no longer manage their medications. But beyond those groups, it’s hard to identify ahead of time who will have problems.

“When you look at all the studies and the demographics — males versus females, low socioeconomic groups and high socioeconomic groups — there’s really nothing that’s much stronger than age and cognition,” Russell said.

Payment reform

Doctors may soon have added incentives to pay attention to medication adherence rates. New payment systems are being discussed that would change the way doctors and hospitals are paid. Instead of rewarding them for each service they provide, these new approaches pay providers based on their ability to manage their patients’ health.

“If you’re responsible not just for the quality, but let’s say a readmission to a hospital because of failed therapy, you’re going to want to be pretty involved,” McLellan said. “As that starts to unfold, we’ll probably want to use a lot more nurse practitioners and physician assistants as well as our office nursing staff to try to do some of that follow up.”

That could mean more clinics will use a team approach like Mosaic’s to monitor medication adherence and keep patients from having costly medical episodes. Severson’s physician, Dr. Tina Busby, believes he would have faced a potentially disastrous outcome had he actually stopped taking his Coumadin.

“Probably given his cardiac risk, he would have had a stroke or other type of clot,” she said. “Potentially, it could have been life ending or he could have had significant morbidity with a devastating stroke.”

Instead, Severson has gotten his heart condition under control and is now trying to work his way into exercising more. His cardiologist recently lowered the dosage of his heart medication, helping to reduce the drug’s side effects. He meets regularly with Charlene Hunt, a nurse at Mosaic who monitors his Coumadin and his other medications, and reports the information back to Busby.

“I can feel pretty confident that even though I can’t see her every day, she is staying on top of changes in my medicine and other things that are going on,” Severson said. “That’s what’s so encouraging to me about where I’m at now.”

Scoring adherence to medications

Despite medication adherence being a significant problem, providers rarely know ahead of time which patients won’t fill their prescriptions. At least two companies however have come up with ways to try to predict how likely individuals are to take their medicine.

One solution comes from FICO, the same company that developed consumer credit scores. In June, the company launched its FICO Medication Adherence score that relies on publicly available data, mainly the type of demographic data used by direct marketers, to predict the likely number of prescriptions filled in the next year. The score ranges from zero to 500, differentiating it from the credit score that can go as high as 850.

The company will sell the scoring service to insurance companies and other health care organizations get more bang for their buck in promoting medication adherence, intervening with those that have lower adherence scores.

While the FICO score does not take into account any medical information or claims data, a system created by pharmacy benefit manager Express Scripts does look at past behavior. The company launched a therapy adherence predictive model last year that factors in a patient’s prescription history, demographics, disease and drug characteristics and other factors to predict adherence among patients with diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

The Express Scripts system will also recommend which interventions, including reminders, consultations with pharmacists, lower co-pays and home delivery, are likely to work best for each patient.

— Markian Hawryluk, The Bulletin