Pioneer principles still infuse Wyoming politics

Published 4:00 am Sunday, December 4, 2011

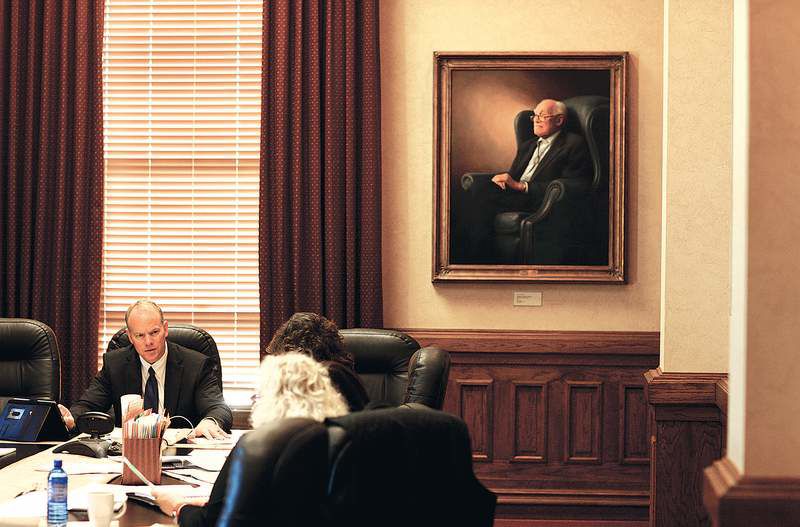

- Wyoming Gov. Matt Mead leads a meeting at the Capitol in Cheyenne, Wyo., in mid-November. A portrait of Mead's grandfather, Clifford Hansen, a former governor, hangs behind him.

CHEYENNE, Wyo. — The rallying cry of “states’ rights” has resonated under many statehouse domes since President Barack Obama’s election, fueled as it usually has been in its many appearances over the years by a ferociously conservative anti-Washington sentiment.

Gov. Matt Mead of Wyoming has another term for it: the pursuit of good government.

If Washington is broken and unable to lead — as millions of Americans believe, according to polls — then who is left to fill the void? Mead’s answer: States functional enough to soldier on through a time of dystopian crisis should be given the room to run. Whether they are led by conservatives or liberals does not matter so much, he said, as the ability to get things done.

“There certainly have to be national policies, and national rules and regulations — I understand that,” Mead, 49, a Republican and former prosecutor, said in an interview in his office here. “But I am in part a states’ rights guy because I think we can do so many things better.”

Better or not, Wyoming’s way — always idiosyncratic in the windblown, rural grain that mixes mind-your-own-business cowboy libertarianism and fiscal penny-pinching — is getting its moment in the spotlight.

An agreement worked out this summer between the state and the Interior Department — which Mead, elected last year, is now trying to sell to his party in the Legislature — would have Wyoming take a different path from other states in managing the gray wolves that have spilled out of Yellowstone National Park since their successful transplant in the 1990s.

The fate of a Clinton-era lawsuit over whether the federal government can protect public lands by barring road development on millions of acres in the West sits on Mead’s desk, too. He has to decide whether to appeal Wyoming’s recent loss in a federal appeals court in Denver.

The state’s experiences in natural gas extraction, especially the controversial technologies of hydraulic fracturing, have come under the microscope as other places around the country see drillers and gas rigs on their horizons.

Whether the spirit here is indeed “something in the soil,” as the historian Patricia Nelson Limerick summed up the regional differences of the West in her book by that title, or something in the personalities of those who stride that soil, political life in Wyoming is decidedly different.

With only about 564,000 people spread across an area nearly twice the size of New York state and an utterly dominant Republican Party, Wyoming is a place where personal relationships and family histories shape debates more than ideology. One of Mead’s grandfathers, Clifford P. Hansen, was governor in the 1960s, and a U.S. senator after that. Mead’s mother, Mary Hansen Mead, ran for governor in the early 1990s.

At the ranch near Jackson where he grew up, Mead said, dinner tables were often graced by people like Dick Cheney, who was a congressman from Wyoming before his national rise, and Alan Simpson, the former Republican senator.

That identity of difference — small-town feel, wide-open spaces — shapes the outlook and the culture.

“In Wyoming, we think of ourselves as a small community with long streets,” said W. Patrick Goggles, the Democratic minority floor leader in the state House, who said he agreed with Mead that whatever Wyoming does right should be bottled as an elixir for the nation’s ills.

“In Wyoming’s case, states’ rights is a valid case,” he said. “I’m not sure I would say that about other states.”

Like Alaska, which is probably Wyoming’s closest cousin, there is a lot of geological luck — a mineral bounty of coal, gas and oil — that helps state leaders take the high, if not haughty, ground in gazing on the struggles of others. The fat stream of revenue from mining and drilling can make fiscal prudence less of a bind.

The overwhelming dominance of one party can also make Wyoming feel a bit like a parliamentary democracy, where one party is empowered top to bottom to run things in a kind of steamroller effect, without gridlock. And the small-town ethos frowns on twisting the knife.

“We are small and we know each other, and while you may be mad at somebody today, in 10 years or 15 years my daughter may be marrying their son,” Mead said. “So the whole notion that it’s ‘burn down the house to get your way’ doesn’t work.”

But there is also a political tradition, Mead said — notably in his family — of admitting error. On wolves, in particular, Wyoming has fought in court for years for its plan that treated the animals as predators — liable to be shot on sight in most of the state. The new compromise plan expands the wolf’s protected zone and allows interconnection with populations in Idaho.

Few people love the compromise. Some environmentalists fear that the numbers will fall too low, while some ranchers bristle that any wolves at all are too many.

A lesson from his grandfather Hansen guides Mead. Hansen, as a young rancher, vehemently fought federal plans to protect lands that eventually became Grand Teton National Park, and then later in life publicly apologized and became a huge supporter of the park.

Saying that wolves are here to stay, Mead made a similar about-face.

“It sticks in the craw,” he said. “But we’ve done the pounding on the table — let’s find a resolution.”