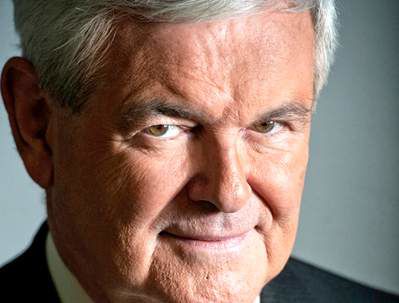

The GOP contenders: Newt Gingrich

Published 4:00 am Thursday, December 22, 2011

- Newt Gingrich

He’s the smart one.

That’s what Newt Gingrich has been hearing since he was little Newtie, the boy who, his stepfather said, had read much of the Encyclopedia Americana by age 12. He’s the smartest guy in the room, the eccentric big thinker of the Republican Party.

Trending

Now, after a 13-year hiatus from politics, the 68-year-old former House speaker is climbing the polls as GOP voters watch him unspool seamless paragraphs on debate stages lined with stammering presidential opponents.

If one hemisphere of the Gingrich brain is chock-full of facts, maybe it’s the other one that tosses the grenades. They are the double helixes of his persona, big thinking and bomb throwing. He is a public-sector version of what business schools call a “disrupter.”

Gingrich is not so much a change agent as an upheaval agent. The man who shattered a 40-year Democratic House majority, upended congressional culture, transformed welfare, shut down the government, married three times and morphed from Lutheran to Southern Baptist to Catholic is no slave to the status quo.

“Americans are astonishingly change-oriented,” he said in a recent interview at his campaign office in Arlington, Va. “They go from BlackBerrys to iPhones. They go from iPhones to iPads. They go from movies to YouTube. It’s the most churning, chaotic society in history.”

And now he wants to be its churning, chaotic leader. His sudden success has legions of longtime Newtologists wondering which Gingrich will dominate his candidacy — or his presidency. The contemplative historian or the combustible politician? Or both?

Pete Wehner, a conservative commentator who has been watching Gingrich operate for more than 20 years, offers a mash-up theory of his rise. “It’s all a combination of intelligence and ambition and drive and ego,” said Wehner. “It’s wanting something and wanting it very badly and being willing to tear up the rules of conduct.”

Trending

The education of Newt Gingrich began when his grandmother in Harrisburg, Pa., taught him to read well before school age. His aunts took him to zoos in Philadelphia and Washington, spawning a love of animals — and a taste for the bold stroke. Before he hit puberty, he walked into a meeting of city leaders to present his plan for a Harrisburg Zoo, complete with a fundraising plan that called for 300 donors to give $100 a month. (They declined.)

“I have an endless interest in everything,” he said. “My whole life has been one long fascination. And then I see something that needs to be improved or fixed or changed, and I try to see if I can help.”

It’s easier to understand Gingrich’s hungry mind than his comfort with chaos. His friends say it’s important to consider just how often the disrupter’s own life was disrupted. His parents divorced almost immediately after his birth in Harrisburg in 1943. His mother soon married an Army colonel named Robert Gingrich, and the family hit the road. With each move — Kansas, France, Germany — the history buff became the new nerd at school.

“He was not born into any inner circle,” said Tony Blankley, a former Gingrich spokesman. “He was an Army brat from Pennsylvania who ended up at a high school in Columbus, Georgia, wearing glasses … in a town full of Southern jocks.”

But Gingrich never responded with meekness when audaciousness would better serve his ambitions. At 19, just weeks after graduating from high school, he asked Jackie Battley, his 26-year-old geometry teacher, to marry him. (She said yes.) One year after getting his first faculty job at West Georgia College, he applied to be chairman of the history department. (They said no.)

At Emory University, he started a chapter of the College Republicans. At Tulane, working on his PhD, he campaigned for liberal Republican Nelson Rockefeller in 1968. Working the hippie-era campus in a coat and tie, he generated a crowd of hundreds to meet the candidate’s plane. “He had an ability to get people involved in things,” recalled Kit Wisdom, who headed the campaign at Tulane. “It was obvious he was going to run for something himself.”

Gingrich began running for something almost as soon as he arrived at West Georgia to teach history in 1970. He lost two campaigns for Congress running as a moderate, environmentalist Republican. Then, in 1978, he ran for a third time as a full-throated movement conservative, attacking his Democratic opponent as a big-government liberal and railing against welfare.

He won and moved his family to Washington. Soon his marriage fell apart — the first of two divorces, each with accusations of infidelity. Gingrich was remarried six months after the divorce was final, to Marianne Ginther, an Ohio woman 15 years his junior. They divorced in 2000 after he began a relationship with Callista Bisek, a Hill staffer. He married the third Mrs. Gingrich shortly after his second divorce.

It was in Washington that Gingrich created the greatest convulsions. Weeks after his 1978 election to the House, he began trumpeting long-simmering accusations of corruption against Charles Diggs, a Detroit Democrat.

There was no other way, Gingrich explains now, to shock a pulse into the comfortably comatose Republican caucus. “You had a leadership that was exhausted and defeated by Watergate,” he said. “They weren’t prepared to fight.”

Thus began his greatest disruption, his years-long siege to take over the House. It was the ultimate combination of brains and brazenness.

He launched a sustained harangue on C-SPAN against the culture of corruption in the entrenched majority. And he filed ethics charges against three more Democrats, including Speaker James Wright over his use of book sales to skirt financial restrictions. Wright resigned in 1989. Eight years later, Gingrich himself would be reprimanded, and fined $300,000, for misleading an ethics committee investigation about his use of a college course for political fundraising.

In 1994, after Gingrich’s “Contract With America” had Republicans nationwide reading from a single set of conservative talking points, the party won its first House majority in 40 years. Gingrich was rewarded with the speakership. Immediately, with a deft blend of combat and compromise with President Bill Clinton, he began to pile up a remarkable record of conservative achievements, including welfare reform and a string of balanced budgets.

But sometimes when Gingrich hits the plunger, what blows up is Gingrich. Jack Howard, Speaker Gingrich’s director of policy, remembers a 1995 meeting in which Gingrich said he was prepared to shut down the government if Clinton didn’t give more ground in budget talks. When Clinton didn’t blink, the shutdown turned into a PR disaster.

Can Gingrich separate his two selves, the brainy and the ballistic? His daughters and former aides say his grandchildren, his marriage to Callista, 45, and his conversion to Catholicism have made him less prone to pull the pin. “I do not think the Newt Gingrich of the 1990s is the Newt Gingrich of 2012,” Martin said. “I think he is more mature. He’s a bit more tempered than he has been in the past.”

But his run for the GOP nomination started with signs that there would be no new Newt. He infuriated conservatives by characterizing Wisconsin Rep. Paul Ryan’s proposed Medicare overhaul as “right-wing social engineering.” Since his political resurrection, he has challenged child-labor laws as “truly stupid” and dismissed Palestinians as an “invented” people.”

But for now, in the chaotic political environment that is Gingrich’s natural habitat, he is on top, a surge built on his debate performances and the GOP electorate’s hunger for someone to shake things up.

• Closing arguments are presented in the preliminary hearing to determine whether Pfc. Bradley Manning will face a court-martial for allegedly turning over hundreds of thousands of classified documents to the anti-secrecy website WikiLeaks. The former security analyst is charged with aiding the enemy and violating the Espionage Act after reportedly leaking the documents in May 2010, while working at a “sensitive compartmental information facility” in the Iraq war zone.

• France’s National Assembly votes on a bill that would make denying genocide a crime punishable with a year in jail and a fine of $59,000. Turkey has appealed to French lawmakers not to back the bill. Armenians say the mass killings of their people in eastern Turkey during World War I was an act of genocide; the Turkish government admits that more than 300,000 people were killed, but refuses to term the deaths “genocide.” Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu warned that the bill would harm relations between Turkey and France.

• Spaniards impoverished by the economic crisis are pinning their hopes on the world’s biggest lottery, which will shower prizes worth a total of $3.3 billion today. The Christmas lottery, which will mark its 200th anniversary next year, is best known for its jackpot — El Gordo, or “The Fat One.” This year’s lottery will award 180 El Gordo prizes worth $5.2 million each. Spain has a more than 20 percent unemployment rate — the European Union’s highest.

The Washington Post has profiled the top-polling Republican presidential candidates. Until the first day of voting — the Jan. 3 Iowa caucuses — we will publish each profile on this page.

Read the profiles that have already run at www.bendbulletin.com/election2012.