Composer’s influence widely known

Published 4:00 am Sunday, December 25, 2011

- Composer’s influence widely known

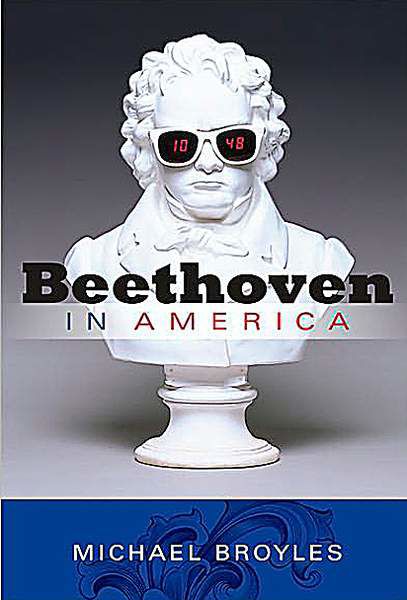

“Beethoven In America” by Michael Broyles (Indiana University Press, 418 pgs. $29)

If we are to believe the Beethoven mythology, which is based mostly on his letters and reports from his inner circle, Beethoven had an unshakeable sense of his own importance. Unlike Mozart and Haydn he refused to defer to nobility, asserting that a composer is of greater value, in the cosmic scheme of things, than a prince. And though he had patrons among the aristocracy, he revered Napoleon, their nemesis, and dedicated his Third Symphony, the “Eroica” (“Heroic”) to him, only to remove the dedication when Napoleon crowned himself emperor.

Trending

Beethoven was probably much as history painted him: the deaf painter in sound, ingenious, embattled and defiant, but also a disheveled, scowling force of nature whose unpleasantness and irritability people suffered for the sake of his brilliance. In his music he tweaked conventions and was undaunted when works like the “Eroica” were criticized for their wildness, harmonic adventurousness and, for the time, outrageous length. Such criticisms aside, an enormous constituency regarded him reverently, and unlike Mahler, who believed that his time would come long after his death, Beethoven knew that he had seized his day.

But even Beethoven probably would have been surprised at the place his name and image have found at the heart of American culture, including popular culture. Yes, it’s true that millions of Americans get through their days, weeks and months without hearing a note of Beethoven or giving him a thought. But as Michael Broyles points out in his fascinating but uneven “Beethoven in America,” just about everyone knows Beethoven’s name, if not necessarily his music, and for millions — particularly those with little interest in the symphonic world — he is synonymous with the classics.

Broyles, a professor of music at Florida State University, places the first American performance of a Beethoven work in Charleston, S.C., just before Easter in 1805 (shortly after the completion of the “Eroica”). Since then, he argues persuasively, Americans have shaped Beethoven as we have seen fit.

He was perfect for that treatment. Within a few decades of his death in 1827, tales of the defiant composer who plowed through a crowd of aristocrats without acknowledging them, and who supposedly shook his fist at the heavens (accompanied by a thunderclap) in his final moments, had filtered across the Atlantic. That image appealed to our “don’t tread on me” sensibility, and Beethoven’s rugged, forceful music captured listeners’ imaginations.

By the 1840s Beethoven was a staple of the nascent American symphonic culture: The first 28 programs by the Philharmonic Society, a predecessor of the New York Philharmonic, founded in 1842, included 17 performances of his symphonies. Boston became even more of a Beethovenian hotbed.

A moral force

Trending

The first part of the book examines America’s fascination with Beethoven in the 19th and early 20th centuries, a time when classical music was regarded as an uplifting moral force, and Beethoven as the zenith of its power. And once Broyles establishes Beethoven in the American concert hall, he shows how early fans turned the composer from a cultural hero into a god of sorts, a fountainhead of edifying, “ethical” music.

Establishing exactly what ethical force a symphony or a piano sonata might have is a tricky business, and Broyles never gets to the bottom of it. But he devotes considerable space to intriguing discussions of Theosophy and Rosicrucianism, both quasi-scientific religious philosophies, whose founders were devoted followers of Beethoven, and who regarded his music not as the work of a human mind but the product of celestial emanations, channeled through Beethoven and meant as a set of cosmic messages to humanity.

Though Broyles does not say so, World War II essentially shattered the notion of classical music as inherently moral. It’s hard to watch film of an orchestra playing Beethoven for an audience of uniformed Nazis and continue to believe that the music has some special moral power. True, the Allies made use of Beethoven too: the opening motto of his Fifth Symphony — da-da-da-dum — is a Morse code V, for victory, and that became the Allied battle cry. Still, the Beethoven as an Ethical Force industry collapsed after the war.

Popular culture

Beethoven as a historical symbol, though, continued to fascinate Americans. Firmly established at the heart of the classical repertory he found his way into popular culture, a process that began long before the war but exploded after 1945. Much of “Beethoven in America” is a copiously annotated catalog of his ubiquity in popular culture.

Broyles discusses the composer’s frequent appearances on the silver screen, either as a biographical subject (as in the fictionalized “Immortal Beloved” and “Copying Beethoven”) or as a philosophically significant component of a film’s soundtrack (as in “A Clockwork Orange,” in which Alex, the film’s antihero, is a Beethoven fanatic) or even merely as an evocative name (as in “Beethoven,” a film about a St. Bernard).

Beethoven turns up regularly in pop music, like Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven” and the rap group Soulja Boyz’s “Beethoven,” with various heavy metal incarnations in between, including the Trans-Siberian Orchestra’s “Beethoven’s Last Night,” an inventive rock opera that involves a deathbed deal in which Beethoven gets the best of Mephistopheles but has to sacrifice his 10th Symphony in the bargain. And though Broyles devotes a section to the Beatles, on the strength of their cover of the Berry song, he neglects a more direct Beethoven connection: the scene in “Help!” in which the Beatles (and others) calm an escaped tiger by singing the “Ode to Joy.”

Sometimes Broyles gets carried away. Few filmgoers are likely to be as convinced as he is that Bobby Dupea, Jack Nicholson’s character in “Five Easy Pieces,” is meant to be a Beethovenian rebel. And he prefers to think of “Roll Over Beethoven” as a young, black rhythm-and-blues guitarist’s shot across the bow of dead, white European composers than as what Berry said it was: a song that had less to do with Beethoven than with his irritation at his sister for monopolizing the family piano to play classical music.

‘So what?’

On the other hand, in a detailed discussion of whether Beethoven was black, as Afrocentrists asserted in the 1970s (using arguments first published in the 1940s, drawing on historical descriptions of Beethoven’s swarthy complexion), Broyles lays out all the evidence suggesting that Beethoven could have had a Moorish ancestor in the 16th century and then quite reasonably concludes, “So what?”

But in a way, that “so what?” can apply to many of Broyles’s observations, because he also demonstrates, perhaps inadvertently, that Beethoven’s universality is in some ways a spent force. Only a handful of pieces — the Fifth and Ninth Symphonies, the “Moonlight” Sonata, the insignificant “Fur Elise” — are heard, over and over, in film, television and pop music, which is where most nonclassical listeners hear Beethoven.

So to the extent that his name is known to everyone, it is as a lowest common denominator of sorts — the one thing they know about classical music. Whether Beethoven would have found this amusing or irritating is impossible to say. But is it really something to celebrate?