Memoir recalls childhood near nuclear facility

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 30, 2012

- Memoir recalls childhood near nuclear facility

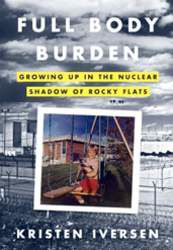

“Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats” By Kristen Iversen (Crown Publishers, 400 pgs., $25)

Like prison wardens and World Cup goalkeepers, book critics toss and turn over the ones that got away. The books they should have pounced upon, that is, but did not.

Trending

One such book, people have been telling me, is “Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats,” by Kristen Iversen. Iversen’s book was issued back in June. I’m getting to it now because I couldn’t shoulder the guilt — my hard-to-please wife is among its importuning admirers — for another day.

Iversen grew up in the 1960s and ’70s in the small town of Arvada, Colo., about 10 miles from Denver, where most of the fathers worked at one of two nearby factories. The first belonged to Coors, whose weak brew was derided as “Colorado Kool-Aid.” More mysterious, and thus prestigious, employment was found at Rocky Flats, a secret nuclear plant where employees made the plutonium warhead triggers for the U.S.’ Cold War nuclear arsenal.

No one knew much about what went on there. The deformed animals, the cancers, the birth defects, the poisoned groundwater, the nuclear accidents that sent clouds of radiation over Denver: Word of these things would seep out slowly, like irradiated treacle.

“Full Body Burden” is a simmering and sickening book that runs on two downward-sloping tracks. The first is the story of Iverson’s largely pastoral middle-class childhood. Her father was a small-time lawyer, the kind of guy whose clients paid with things like bearskin rugs. Her mother was a housewife. Iversen and her three siblings had dogs and horses and ran unfettered in the rural outdoors.

She is good on the family details: the hamburger casseroles, the liquor-soaked cherries from her father’s cocktails, the Polynesian-style wet bar he buys for the basement. From their backyard at night Rocky Flats glows in the distance. “The lights from Rocky Flats shine and twinkle on the dark silhouette of land almost as beautifully as the stars above,” Iversen writes, “but it’s a strange and peculiar light, a discomforting light, the lights of a city where no true city exists.”

This book’s other track is serious investigative journalism. Iverson has delivered an intimate history of the environmental abuses at Rocky Flats, which opened in 1952, and the history of how those abuses have been systematically covered up. Commenting on a 1970 nonprofit report, a University of Colorado biochemist said the plutonium deposits in the soil outside Rocky Flats were “the highest ever measured near an urban area, including the city of Nagasaki.”

Trending

An Energy Department survey, Iverson writes, found Rocky Flats to be “the most dangerous site in the United States.” She adds: “Two buildings at Rocky Flats make the list of the 10 most contaminated buildings in America.” One of them is No. 1.

For a while you think these two narratives won’t quite come together. But they do, in powerful ways. Iversen watches people she knows get sick and die. She herself has swollen lymph nodes removed, a surgery so common near the Hanford, Wash., nuclear complex, she learns, that the mark it leaves on one’s neck is referred to there as a “downwinder scar.”

More impressively, “Full Body Burden” — the title refers to the amount of radioactive material at any time in a human body — becomes a potent examination of the dangers of secrecy.

Her family falls apart because of the secrets it keeps. Her father’s alcoholism isn’t discussed, until he loses his job and finally becomes a cabdriver and a broken man. Her mother’s pills are never mentioned either. Iversen and her siblings drift apart. The author, before and during college, takes jobs in places like truck stops in order to get by. For a while she is a secretary inside Rocky Flats.

Iversen is even more devastating about the secrecy that surrounded Rocky Flats, the vital health information that was suppressed over the decades. Part of this suppression was the community’s own denial. “Anyone who criticized Rocky Flats — or even spoke of it — was ridiculed or ignored,” she says.

“Full Body Burden” ends on a particularly sinister note. Rocky Flats, after decommissioning and a cleanup effort, has been declared a wildlife refuge. The secrecy holds still.