Cascades once home to wolverines

Published 4:00 am Saturday, December 8, 2012

- Cascades once home to wolverines

The trap is clever, designed to reveal as much as possible about one of the most reclusive animals in the wild while only plucking out some of its fur and taking its photo.

Built around a 15- to 20-pound block of road-killed deer, the contraption led to the recent discovery of three wolverines in the Wallowa Mountains of Eastern Oregon, where scientists and locals alike believed the animals roamed no more. Now the focus is on the Cascades near Bend and the possibility of wolverines hiding here. Wolverines haven’t been seen in the Central Oregon Cascades for more than 45 years.

But, “there hasn’t really been a large-scale detection effort,” said Tim Hiller, carnivore-furbearer program coordinator for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Until now.

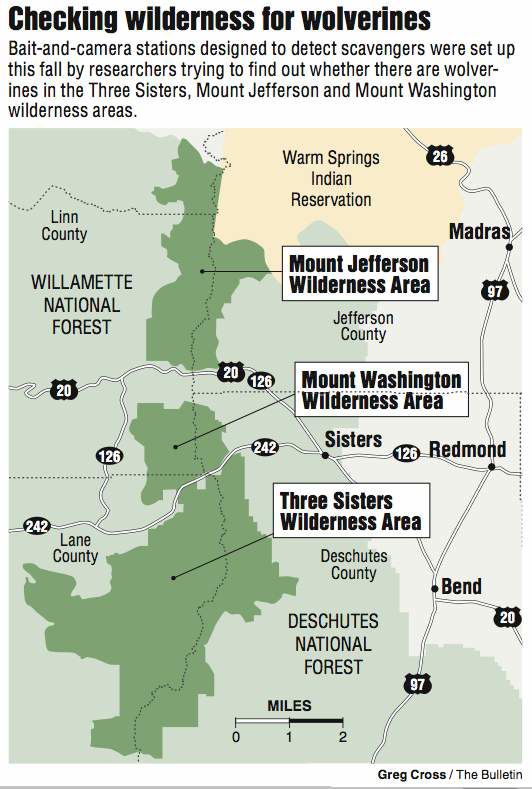

Hiller and his wife, Jamie McFadden, are leading a research project aimed at determining whether wolverines are living in the Cascades. Their focus is the Three Sisters, Mount Jefferson and Mount Washington wildernesses areas. The last wolverine in Central Oregon mountains was killed in 1969 by a trapper near Broken Top, said ODFW officials. Stuffed, the animal now stands preserved at the ODFW office in Bend.

In the West, wolverines weigh up to 35 pounds and live about 15 years, said Audrey Magoun, a wildlife biologist and wolverine expert. While they often are labeled as mean or ferocious, she said they aren’t.

“No more so than other animals,” she said.

She has never heard of a wolverine, which is in the same family of animals as badgers, martens and weasels, ever attacking anyone. Their mean reputation, Magoun said, likely comes from the disposition they displayed when people found wolverines in traps.

Although not targeted by trappers in the 1800s like beavers, trapping in Oregon did play a part in the decline of the wolverine, Magoun said.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, sheep ranchers and other livestock managers regularly set out poisoned baits to rid mountains like the Wallowas of predators, such as wolves, cougars and coyotes. Again, the wolverines weren’t targeted, but their numbers shrank and they may have been wiped out of the state completely.

Any population of wolverines can be hard to find. They cover wide ranges over rough terrain, making them a difficult animal to find, let alone study.

“They are just natural low-density animals, even in high-quality habitat,” Hiller said.

The first year of Hiller and McFadden’s research is costing about $100,000, said Tim Greseth, executive director at Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation. The Portland-based group funds wildlife research around the state. The largest grant, $40,000, is from the U.S. Forest Service. The Oregon Zoo, the Norcross Wildlife Foundation, ODFW and the Wolverine Foundation are also supporting the project.

A second season of research is planned for next winter and spring. Greseth said the group is trying to raise about $75,000 to fund it.

Listed by the state as a threatened species since 1975, the wolverine is also a candidate for federal Endangered Species Act protections in Oregon.

“Our interest is in knowing more about what species are in the state,” he said.

Cameras set

Since October, McFadden has been installing bait-and-camera stations around the Cascades, having installed the 20th and final station Thursday, Hiller said. The stations are near avalanche chutes high in the mountains, around 7,000 feet and higher, where snow typically stays thick into spring.

Wolverines tunnel through such snow, building dens where they raise their young. Determining whether the animals are breeding in the Cascades is the second goal after first figuring out if they’re here or not.

This is where that chunk of dead deer comes into the research. Wolverines hunt and scavenge for food, with a deer quarter a definite draw.

“It’s all about attracting the animal and enticing them to the area, but not giving them an easy meal,” Hiller said.

Strung from trees, the bait hangs over a stand that the wolverine must climb to reach the meat. On the way up the animal triggers clips that take a pinch of its hair, which provides a DNA sample, and activates a motion-sensitive camera that photographs its underbelly.

Wallowa wolverines

Magoun designed the bait-and-camera station and even wrote the 160-page how-to manual for other wolverine researchers. The stations allow scientists to track wolverines without having to capture and collar them. Capturing the animals may be traumatic for them, and the relatively light weight of the wolverine makes it hard for the animal to bear the weight of the batteries required for a long-lasting radio or GPS-tracking collar.

The photos in the bait-and-camera system allow scientists to track the animals’ movements if they move from station to station. Photos of the underside of the wolverines may show distinctive fur patterns, their gender and whether the females are feeding young.

Having studied wolverines since 1978, mainly in Alaska, Magoun bought a house with her husband about five years ago in the northeast Oregon outpost of Flora. The couple splits time between there and Fairbanks, Alaska. From the back of the home, on a clear day, she could see the rocky Wallowa Mountains.

While she was told wolverines no longer roamed the mountains, she was sure they were there. The mountains, she said, are just the right kind of wolverine habitat.

Conducting a survey for the Wolverine Foundation, an international nonprofit group that advocates for the animal, Magoun went in search of wolverines in the Wallowas. In the winter of 2010-11 she set up 16 motion-activated cameras around the mountains and she found evidence of three wolverines, likely all males.

The year before, in 2009, cameras set by other researchers also captured images of wolverines on Mount Adams in Washington and in the Sierra Nevada in Northern California.

Last winter only one of the Wallowa wolverines, which Magoun calls Stormy, was photographed again. That suggests that it may be a resident while the other two wolverines were just passing through the Wallowas. She’s setting up cameras again this winter to test her theory.

Like wolves, wolverines will wander far from where they were born in search of new territory and a mate. A wolf from a pack from the Wallowas — known as OR-7 by his GPS collar number — became a media celebrity late last year when he traveled into California, the first known wolf in the Golden State in nearly 90 years. Two months earlier OR-7 crossed through Central Oregon.

“If wolves are traveling from northeastern Oregon all the way to California, certainly wolverines could,” Magoun said.