Durning, 89, was prolific character actor

Published 4:00 am Wednesday, December 26, 2012

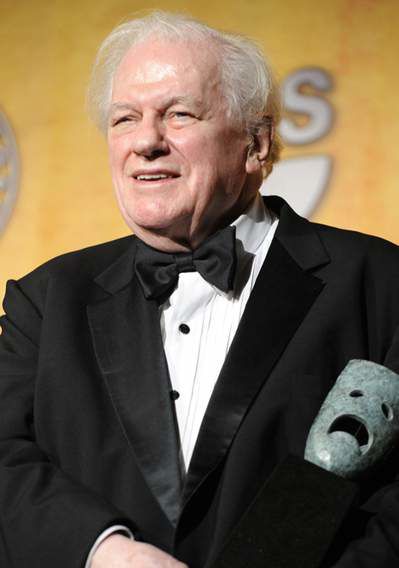

- Charles Durning, pictured in 2008 on the night he won a life achievement award from the Screen Actors Guild, was nominated twice for an Academy Award and nine times for an Emmy Award, although he won neither.

Charles Durning, who overcame poverty, battlefield trauma and nagging self-doubt to become an acclaimed character actor, whether on stage as Big Daddy in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” or in film as the lonely widower smitten with a cross-dressing Dustin Hoffman in “Tootsie,” died Monday at his home in Manhattan. He was 89.

His daughter, Michele Durning, confirmed the death.

Charles Durning may not have been a household name, but with his pugnacious features and imposing bulk he was a familiar presence in American movies, television and theater, even if often overshadowed by the headliners.

Alongside Paul Newman and Robert Redford’s con men, Durning was a crooked cop in the 1973 movie “The Sting”; starring with Nick Nolte, he was a dedicated assistant football coach in “North Dallas Forty” (1979); in the shadow of Robert De Niro, he was a hypocritical power broker in “True Confessions” (1981).

If his ordinary-guy looks deprived him of leading-man roles, they did not leave him typecast. He could play gruff and combative or gentle and funny. In the comedy “Tootsie” (1982) he was a little of each, playing Jessica Lange’s unsuspecting father, who falls for a television actor masquerading as a woman.

Not surprisingly, Durning’s two Oscar nominations were for supporting roles, as a slippery governor in the Burt Reynolds-Dolly Parton musical “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” (1982) and as a lustful Nazi colonel in the 1983 remake of “To Be or Not to Be,” starring Mel Brooks and Anne Bancroft.

His television credits were voluminous, from guest spots to substantial parts in TV movies and mini-series. He was a regular on “Evening Shade,” the 1990s sitcom that starred Burt Reynolds, and “First Monday,” a short-lived 2002 drama about the Supreme Court. He had recurring roles as a priest on “Everybody Loves Raymond” and as the ex-firefighter father of Denis Leary’s Tommy in the firehouse series “Rescue Me.” In all, Durning received nine Emmy Award nominations, although he never won.

His Big Daddy, the bullying, dying plantation owner in a 1990 Broadway revival of Tennessee Williams’ “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” brought him a Tony Award for best featured actor in a play. Frank Rich, then the chief drama critic for The New York Times, likened the performance to “a dying volcano, in final, sputtering eruption.”

“Cat” was Durning’s first Broadway hit since 1972, when he drew praise as a small-town mayor seeking re-election in “That Championship Season,” Jason Miller’s Tony-winning drama about the reunion of a high school basketball team.

Despite his success, Durning fought a lifelong battle with himself.

“I lack confidence as an actor,” he told The Toronto Star in 1988. When asked what he thought his image was, he replied: “Image? Hell, I don’t have an image.” He later told The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette that he was “driven by fear — the fear of not being recognized by your peers.”

Charles Edward Durning was born into poverty on Feb. 28, 1923, in the Hudson River village of Highland Falls, N.Y., the ninth of 10 children. His father, James, an Irish immigrant, had been sickened by mustard gas and lost a leg in World War I. He died when Charles was 12. Five of Charles’ sisters died of either smallpox or scarlet fever in childhood, three of them within two weeks.

Never a good student, young Charles dropped out of school and fled to Pennsylvania, deciding that his mother, Louise, a laundress at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, would fare better with one less mouth to feed. He worked as a farmhand and did other menial jobs before moving to Buffalo, where again he took odd jobs. One, opportunely, was as an usher in a burlesque house.

One night a frequently drunk comedian failed to show up, and Durning, who had memorized the comic’s jokes, persuaded the manager to let him go on. He “got laughs,” he later recalled, and was “hooked” on show business. He made his stage debut in Buffalo.

Then came World War II, and he enlisted in the Army. His combat experiences were harrowing. He was in the first wave of troops to land on Omaha Beach on D-Day and his unit’s lone survivor of a machine-gun ambush. In Belgium he was stabbed in hand-to-hand combat with a German soldier, whom he bludgeoned to death with a rock. Fighting in the Battle of the Bulge, he was among the few to escape the Malmedy massacre, where German troops opened fire on about 90 American prisoners.

After the war, a mentally troubled Durning “dropped into a void for almost a decade” before deciding to study acting at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York, he told Parade magazine in 1993. The school dismissed him within a year.

He went from job to job, from doorman to dishwasher to cabdriver. He boxed professionally for a time, delivered telegrams and taught ballroom dancing. Every so often he landed a bit part in a play.

His big break came in 1962, when Joseph Papp, founder of the Public Theater and the New York Shakespeare Festival, invited him to audition. It was the start of a long association with Papp, who cast him, often as a clown, in 35 plays, many by Shakespeare.

Durning preferred the stage to movies, finding roles in Dennis J. Reardon’s “Happiness Cage,” “The World of Gunter Grass” and Ernest Thompson’s “On Golden Pond,” among other plays.

His work in “That Championship Season,” led film director George Roy Hill to tap Durning for the part of a corrupt police lieutenant in “The Sting.” Two years later he played a beleaguered police hostage negotiator squaring off against Al Pacino’s manic bank robber in Sidney Lumet’s celebrated “Dog Day Afternoon.”