Will drones revive aviation industry?

Published 4:00 am Sunday, February 17, 2013

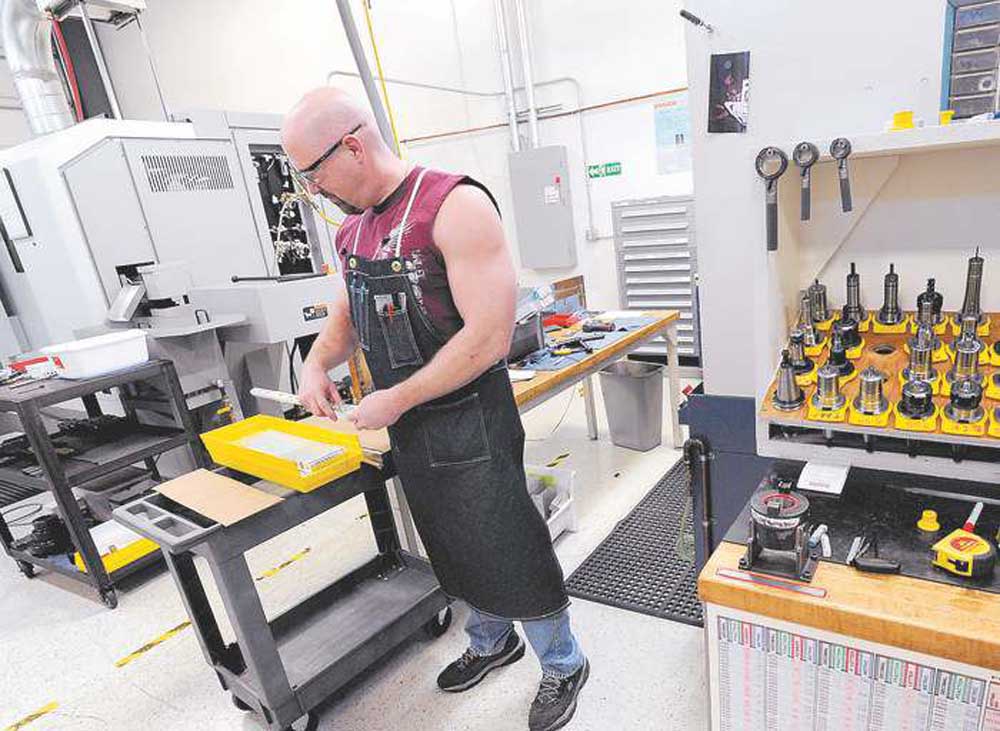

- Machinist Mark Hartley inspects finished parts at Outback Manufacturing in Bend. Among other products, the company makes parts for unmanned aerial vehicles, or drones.

Launching unmanned vehicles into the High Desert sky may be the tonic Central Oregon’s aviation industry has craved since Cessna and its 400 jobs left Bend.

While the single-engine planes of Cessna and others drove the aviation manufacturing industry in Central Oregon for years, economic development officials are looking now to the unmanned aerial industry as the next-generation job creator.

Trending

The Federal Aviation Administration kicked that effort into high-gear Thursday.

After months of delay, the agency announced the start of the process to pick six sites across the United States for the testing of drones, called unmanned aircraft systems by industry officials.

The site selection is part of an effort to integrate unmanned aircraft into civilian aviation by the end of 2015. The FAA predicts more than 10,000 of these vehicles will be flying over America’s skies by 2017, doing a combination of military training, search and rescue, geographical surveying, forest fire detection and other tasks.

Central Oregon’s business leaders want to bring as many drones here as possible. Their push comes amid increasing national concerns over the potential for drones to spy on citizens.

Some drones are about the size of piloted military jets, weighing several tons. Others are the size of a kitchen plate, or smaller.

At stake is the chance to recruit new high-tech companies to the region and create a hub for unmanned aerial vehicles in the Pacific Northwest.

Trending

A 2011 study by Economic Development for Central Oregon estimated that getting a test-site designation would create nearly 500 jobs within seven years, adding $28 million in payroll to the region and nearly $75 million in total economic benefits.

Those projections are still on track today, and could be even higher, said Roger Lee, EDCO’s executive director.

“I know we’ve had more than a dozen companies say, ‘We will set up operations in Central Oregon if you get one of those sites,’” Lee said.

It’s far from a given that Central Oregon, or the state as a whole, can successfully lobby for one of them. Thirty states are expected to submit applications, according to a spokeswoman for the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International, a global advocacy group for the unmanned systems industry.

Florida has the backing of a massive aerospace industry to help in its push. Ohio announced plans last year to partner with Indiana and establish an unmanned vehicle “test complex” for researchers to develop new technology. The governor of Oklahoma has established an Unmanned Aerial Systems Council as its catalyst for a test site.

Oregon State University is leading the charge here. The university is working with EDCO on what they call a multiregion proposal for testing drones. OSU formally announced its push to land one of the sites in January.

“The way we want to see a site set up is with multiple geographic areas” across Oregon for unmanned vehicle launches, said Rick Spinrad, vice president for research at OSU.

The Northwest has a network of existing companies specializing in drone activity. Insitu Inc., a Boeing subsidiary, builds unmanned vehicles just across the Columbia River from Hood River. Northwest UAV Propulsion Systems operates in McMinnville, and FLIR Systems develops thermal imaging technology for multiple purposes, including unmanned systems, in Wilsonville.

Other criteria for site selection includes geographic and climactic diversity. The FAA wants a variety of test conditions to fly different kinds of unmanned vehicles. Oregon offers plenty of geographical variety, Spinrad said, with coastal areas to the west, mountainous terrain along the Cascades and open desert in the east.

It also has the airspace.

Spinrad pointed to a pair of areas in the region that could be suitable for flying. One is in the northwest corner of an area east of Bend called the Juniper Operations Area. The space, used for military operational training by the Oregon Air National Guard, covers nearly 5,000 square miles over Deschutes, Crook, Lake and Harney counties.

The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs has also expressed interest in using some of its land for testing.

But concerns that law enforcement agencies could invade citizens’ privacy has entered the debate. A leaked legal memo outlining the Obama administration’s justification for using drones to potentially target American terrorism suspects abroad cast scrutiny on the issue earlier this month.

And Oregon Senate Bill 71, introduced by Sen. Floyd Prozanski, D-Eugene, seeks to restrict certain law enforcement uses for drones.

Lee said he worries those concerns could derail his group’s efforts to expand drone testing.

“I think with these privacy concerns, people have in their minds an image of the Terminator taking over the planet,” he said, adding that the language of SB 71 is vague enough to potentially restrict large-scale implementation of unmanned vehicles in Oregon.

“Most of the applications we have in mind are for commercial use,” like geographical surveying and forest fire detection, he said.

A spokesman for Prozanski said the Senator plans to amend the bill in the coming weeks so that it doesn’t hamper development efforts, but applies only to certain uses of drones by police.

Advocates for an expanded drone presence in Oregon said Thursday that they were still reading the 68-page FAA memo outlining the test-site criteria. They said it was too early to comment on many specifics about what Oregon’s submission may look like. States have until May 6 to turn in their applications.

Even without a test site, the requirement to integrate drones into civilian skies by 2015 means universities like OSU will keep developing new drone technology, giving companies around the state a chance to benefit. The FAA issues certificates of authorization to public groups conducting drone testing research. It’s an avenue OSU has been pursuing and plans to follow independent of its test site application, Spinrad said.

But the economic impact from the test sites figures to be huge.

The effort isn’t lost on companies like Outback Manufacturing, a Bend business that makes machine parts, including some for drones.

Outback would almost certainly add to its 21-employee workforce if Central Oregon becomes part of a test site, said Vice President John Lynch.

“I can’t see how it wouldn’t,” Lynch said. “That’s the same with dozens of other manufacturing companies in town … This effort kind of started when Cessna had just closed down and general aviation had sort of collapsed here. Those (Cessna) workers are the same kind of people you would need for unmanned vehicles. They’re already trained to work with carbon fiber and wiring. A (drone) is still a plane, just without a person inside.”