‘In Cold Blood:’ Nonfiction novel collides with facts

Published 5:00 am Sunday, March 24, 2013

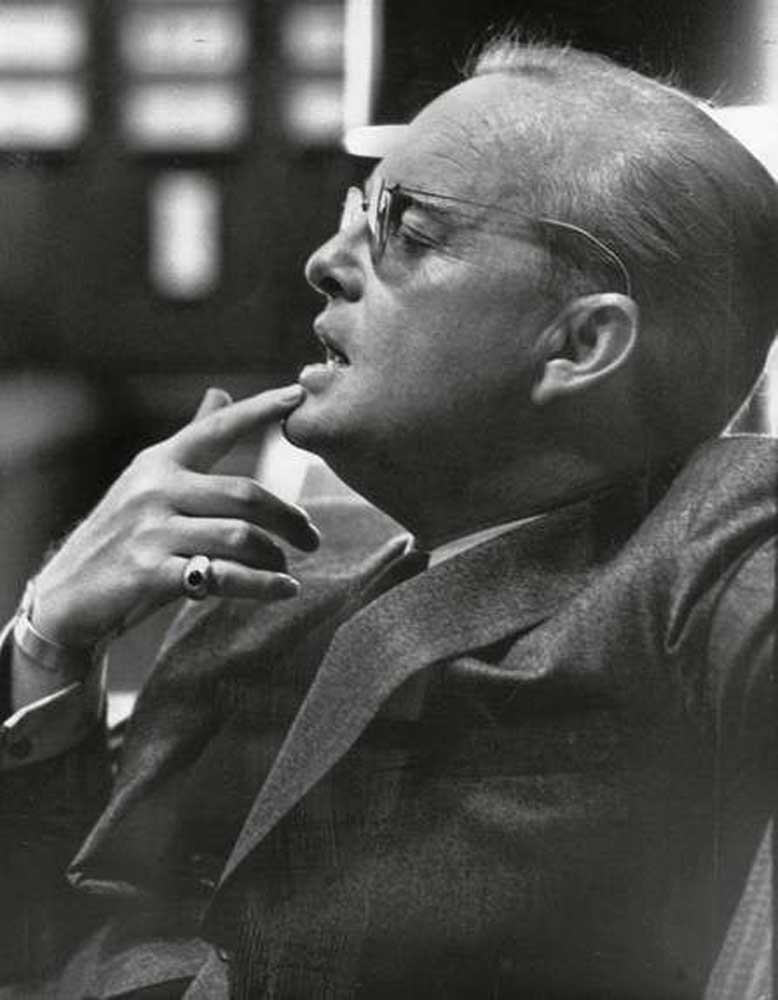

- When “In Cold Blood” was published in 1965, author Truman Capote, pictured in 1969 in a visit to Random House in New York City, touted his work as a completely true literary account of a shocking mass murder in Kansas. Subsequent fact-checking has shown that to not be the case.

NEWARK, Del. — In the light of history it’s clear that however great Truman Capote’s literary gifts, his promotional genius surpassed them.

The key theme in the publicity campaign he masterfully engineered for “In Cold Blood” — published as a four-part series in The New Yorker in the fall of 1965, and subsequently as a book — was that, despite having the stylistic and thematic attributes of great literature, the account of four brutal murders in Kansas was completely true.

Trending

At the top of The New Yorker series was an “Editor’s Note” reading, “All quotations in this article are taken either from official records or from conversations, transcribed verbatim, between the author and the principals.” The book’s subtitle was “A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences.” In interviews, Capote kept talking about the brilliant genre he’d concocted, the “nonfiction novel,” and colorfully described the methods he’d devised to ensure his work’s veracity. A New York Times reporter drank it all in and wrote:

“To record real life, (Capote) trained himself for two years in remembering conversations without taking notes. Friends would read to him and he would try to transcribe what he had heard, eventually reaching the point where he was 92 percent accurate.”

Almost from the start, skeptics challenged the accuracy of “In Cold Blood.” One early revelation (acknowledged by Capote before his death in 1984) was that the last scene in the book, a graveyard conversation between a detective and the murdered girl’s best friend, was pure invention. I myself made a small contribution to the counter-narrative. While doing research for my 2000 book, “About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made,” I found “In Cold Blood” galley proofs in the magazine’s archives. Next to a passage describing the actions of someone who was alone, and who was later killed in the “multiple murder,” New Yorker editor William Shawn had scrawled, in pencil, “How know?” There was in fact no way to know, but the passage stayed.

Over the years, many additional holes have been found in “In Cold Blood.” In the first of two notable recent revelations, a Wall Street Journal article suggested that the Kansas Bureau of Investigation waited five days before following up on what turned out to be the crucial lead in the case, rather than doing so immediately, as Capote wrote.

This is not a trivial matter, because if the KBI had acted quicker, the killers — Perry Smith and Dick Hickock — may not have made it to Florida, where, according to a separate investigation by the Sarasota Herald-Tribune, they possibly committed four additional murders, of a husband and wife and their two young children.

The mistakes in “In Cold Blood” are especially striking because the material originally appeared in The New Yorker, which, along with Time magazine, originated the practice of fact checking and has for many years been famous for the reliability of its content. I recently discovered that the New Yorker staffer assigned to check “In Cold Blood” was a man named Sandy Campbell, and that Campbell’s fact checking file for the story is in the special collections of the library of the University of Delaware, where I work. The file has not been mentioned in any book or article about Capote or “In Cold Blood” that I’ve found; as far as I can tell, no one has previously examined it in the context of the book’s veracity. Now that I’ve done so, I think I understand why the story passed muster at The New Yorker, stretchers and all.

Trending

But verifying the “nonfiction novel” aspects of the article does not seem to have been part of Campbell’s brief. They are, in any case, not underlined.

“In Cold Blood” was filled with scenes, dialogue and interior monologues. Many of them involved Hickock and Smith, who had not yet been executed at the time Campbell commenced his checking. Today’s fact checkers would talk to them; Campbell did not. Other scenes were literally impossible to check. For example, early on, there is an exchange between Nancy and Kenyon Clutter, a brother and sister who would be murdered later that day:

“ ‘Good grief, Kenyon. I hear you!’

As usual, the devil was in Kenyon. His shouts kept coming up the stairs.

‘Nancy! Telephone!’

Barefoot, pajama-clad, Nancy scampered down the stairs.”

Campbell made no marks next to the passage.

It is theoretically possible that another checker may have worked on the piece, and focused on these elements of the story. But it seems highly unlikely.

In any event, by the standards of 1965, “In Cold Blood” checked out impressively well, at least according to Campbell. Anne Taylor Fleming interviewed him in 1978 and reported him saying that “he had never seen such an accurate account and that whatever the fiction veneer, ‘In Cold Blood’ was a scrupulous nonfiction report.”

At only one point in the galleys did Campbell indicate an interest in matters that went beyond facts in the narrow sense of the word. But even in this instance, he acted less like a fact checker than a story editor who’d spotted a piece of foreshadowing that hadn’t been followed through on. In one early scene, Nancy Clutter says to Kenyon that she keeps smelling cigarette smoke in their house. She mentions this again, in a phone conversation with her best friend. Capote never returns to the question of the strange odor. On the first page of the first set of galleys, Campbell wrote, “Is there ever an explanation of Nancy smelling cigarette smoke?” Like William Shawn’s “How know?,” his question never got an answer.