Former couple take fight over frozen embryos to court

Published 5:00 am Tuesday, September 24, 2013

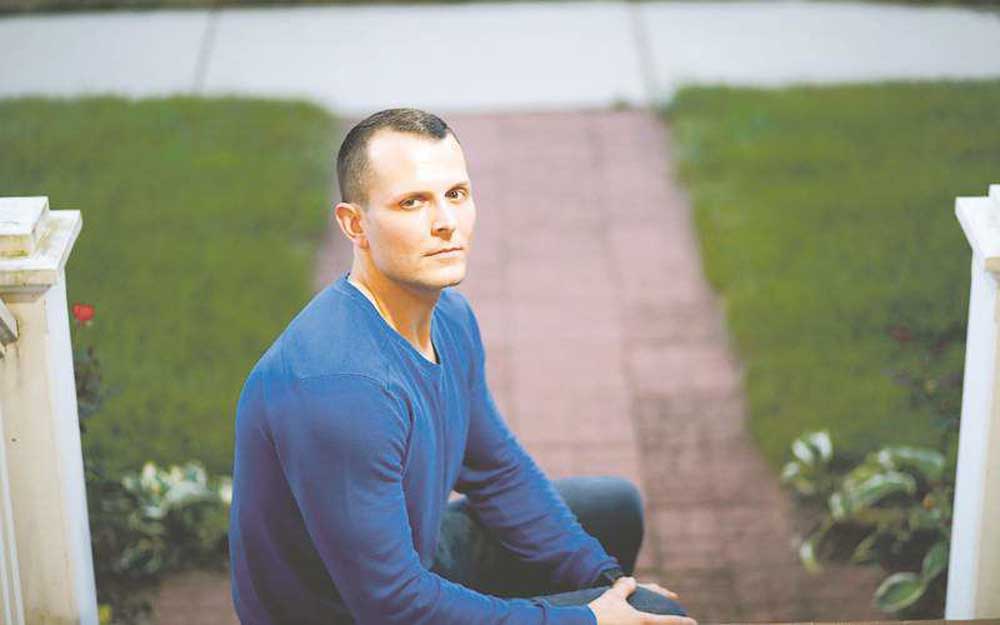

- Jacob Szafranski is in a legal dispute about the use of embryos which he and his former girlfriend, Karla Dunston, had fertilized in 2010. Doctors and attorneys across the country are watching the case, which the Illinois Supreme Court is expected to weigh in on later this month.

CHICAGO — He was a charming nurse in a northwest suburb. She was an attractive emergency room physician at a local hospital. For nine years, their work lives overlapped until, eventually, their friendship evolved into something more.

But five months into their romantic relationship, in March 2010, Karla Dunston was broadsided by a devastating diagnosis: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The window was already closing on the 39-year-old’s fertility, and chemotherapy would slam it shut for good. She asked her boyfriend, Jacob Szafranski, if he would provide his sperm, which would be combined with her eggs to create embryos, allowing her to one day have a biological child, according to court documents.

One week later, the couple found themselves at Northwestern Hospital’s fertility clinic, depositing genetic material to be frozen and later retrieved for in-vitro fertilization.

But the relationship unraveled two months after their trip to the clinic, and now their break-up could have repercussions that reach far beyond one couple. In a case before the Illinois Supreme Court, the Elgin man argues that he never agreed to give up a say in whether he becomes a parent, that forced procreation would violate his constitutional rights. His ex-girlfriend insists that she has the right to have her biological child, and she should control the destiny of the embryos.

As reproductive technology outpaces the law, the case is being watched by physicians and attorneys across the country. The Illinois Supreme Court is expected to weigh in on Szafranski v. Dunston — and the fate of three embryos cryo-preserved at Northwestern — later this month.

Looking back on his decision to participate, Szafranski, 32, told the Tribune: “It was a very emotional time and I was just trying to support Karla the best way I could.”

The decision was made under duress, Szafranski said. Later, he was willing to find a way to give Dunston control of the embryos as long as the child could never be traced back to him. More recently, he concluded there were no guarantees of anonymity, and he decided he didn’t want to procreate at all.

Dunston, in a court deposition, remembered those same initial, overwhelming days: “I thought about my different options, of using a sperm donor or someone that I knew for many years and that was a wonderful person. So I decided to go with someone that I thought was a wonderful person and I trusted.”

Dunston is not seeking any support, financial or otherwise, from Szafranski and wants only the opportunity to have her biological child, her attorney said.

Not long ago, the idea that a couple could combine their sperm and eggs in a test tube to create embryos, then freeze, thaw and implant them and end up with a healthy baby seemed like science fiction. In 1985, 260 babies were born through assisted reproductive technology; in 2010, the number topped 61,000, according to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Yet, only about six state higher courts have addressed, with mixed results, what to do with frozen embryos once a couple has separated.

So, now people are watching to see how Illinois handles the issue. A Cook County trial court had awarded Dunston rights to the embryos. But Szafranski appealed and the higher court sent the case back, clarifying that the case centers on prior agreements rather than the interests of either potential parent.

Now legal experts are asking what constitutes those earlier pacts. Is it the medical consent form the couple signed requiring joint consent for any use of the embryos? Is it that Szafranski provided his genetic material and wrote to Dunston that he “wanted to help her have a baby?”

Or is it a co-parenting agreement drawn up by an attorney giving Dunston control over the embryos even without Szafranski’s consent — a document that the couple never signed?

“What sets this case apart is that the existence and scope of the contract is less certain than in all other cases,” said Judith Daar, a professor at Whittier Law School in Costa Mesa, Calif., and author of a textbook on assisted reproductive technology law. “The court can look to the medical forms, the unsigned co-parenting agreement or the parties conduct to determine the terms of any contract.”

No doubt that when Dunston approached Szafranski, neither could have imagined such a complex legal quagmire. Given the urgency of starting cancer treatment, events moved quickly and on March 25, 2010 — one week after Dunston’s diagnosis — Szafranski was handing over a sample at Northwestern.

The couple also signed a document stating “no use can be made of these embryos without the consent of both partners.” They met with the clinic’s attorney, Nidhi Desai, to discuss the legal ramifications of in vitro fertilization. A co-parent agreement would give Dunston sole control of the fertilized eggs but was never signed.

Szafranski said that initially he was honored by the request to help his girlfriend. But later he had deep reservations, said Szafranski, who broke up with Dunston in May 2010, ending the relationship after about seven months.

“This experience has been personally and emotionally damaging to me. It has profound implications for my life …and I have the right not to be a father,” he said. “It’s something I take very seriously and feel very strongly about.”

Court records show Dunston wrote to Szafranski in a September 2010 email: “I had a chance to use a random sperm donor and you took that away from me by agreeing to help. I trusted you and now you are trying to take away my chance of having a biological child. … Those embryos mean everything to me, and I will fight this to the bitter end.”

Dunston, through her attorney, declined to be interviewed for this story.