Songs of protest

Published 10:26 am Friday, November 15, 2013

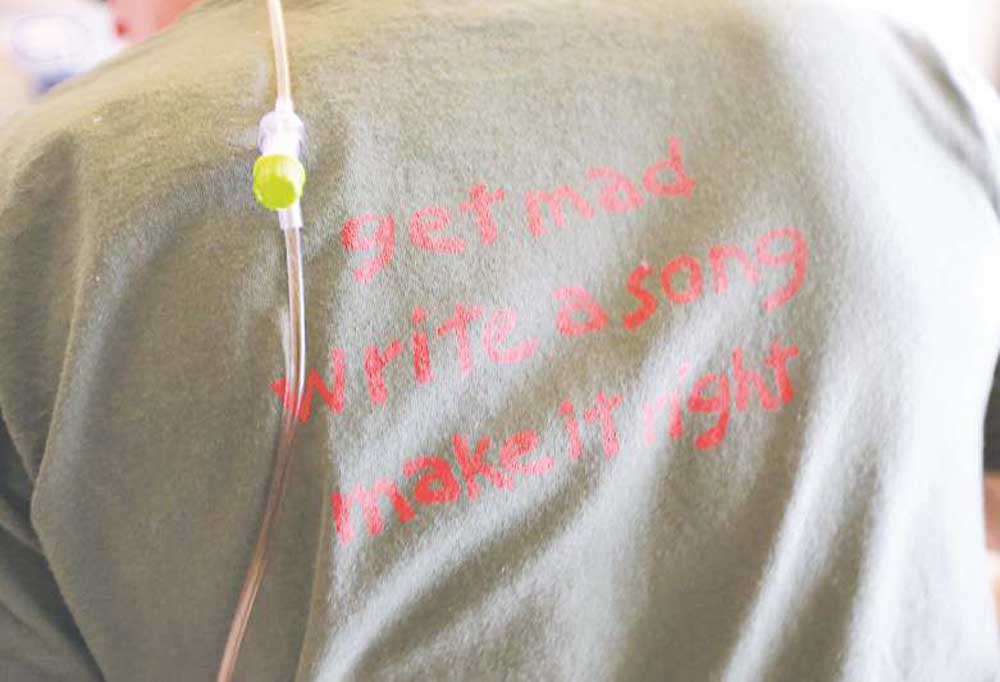

- With the tube to an IV bag draped over his left shoulder, Bill Valenti shows off a T-shirt that explains the call he feels to write protest songs and encourages others to do the same.

Seated in a hospital bed with the tube from an intravenous drip bag running into his left arm, Bill Valenti grabbed his guitar and started playing a few verses from his latest song — “The No Good Blankety-Blank Chemotherapy Blues” — to break the silence.

“The news sent me reeling, I can’t describe the feeling, when the ‘Big C’ stepped into my way,” the 64-year-old musician sang while a group of nurses doing their rounds at St. Charles Bend listened to his impromptu performance.

Trending

Back in September, Valenti’s doctor’s told him his non-Hodgkin lymphoma metastasized into triple-hit lymphoma — a rather aggressive form of blood cancer — and prescribed four months of chemotherapy before he gets a bone marrow transplant this winter.

Valenti wrote “Chemotherapy Blues” to describe this experience and how his doctors said their “aim is to kill all the bad stuff (in his body with the toxins contained his his drip bags) without killin’ you.”

“(This song is) an expression of what I’ve been going through,” said Valenti, a baby boomer who is continuing his generation’s love for protest music by penning songs about political and other issues.

Every generation has musicians who express their ideas and experiences through song. These musical compositions fall into the category of protest songs, said Bend community radio DJ Michael Funke, when they focus on an issue or the musician thinks needs to be addressed.

“There will always be musicians who are aware of the world around them,” said Funke, who features protest or political music on his KPOV radio show. “And when they see (stuff they don’t like), they feel compelled to write songs about it.”

Some people argue protest music had a golden age during the 1960s, when the baby boomers — the generation born between 1946 and 1964 — transitioned from adolescence to adulthood at a time that was bookended by the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War.

Trending

But other people argue that writing protest or political songs is part of a greater tradition of music that started long before songs written by Bob Dylan, Pete Yarrow, Joe McDonald and John Lennon dominated the airwaves, and continues today.

“All communities have songs that are political,” said Loren Kajikawa, a professor with the University of Oregon’s School of Music who teaches a course on political and protest music. But while the idea of writing protest songs is universal and timeless, he said baby boomers often gravitate back to the music of the 1960s because “every generation looks back on the things that were important to them when they were growing up.”

The ’60s

Funke said the very act of listening to rock ‘n’ roll during the early to mid-1950s and 1960s was considered to be an act of protest because the genre brought black artists and white artists together and gave them the chance to perform in front of a mixed audience.

“That freaked a lot of people out,” said Funke, who also remembers how listening to the music that came out during that time period was a social activity in itself. “When the Rolling Stones came out with a new album, my friends and I would get together, listen to it, and then we would talk about it.”

Funke said the energy and the structures that embodied his generation’s early experiences in music created the perfect environment for the political music that made the soundtrack for a decade when people challenged the status quo and the values that had been handed to them.

“When you think of protest music the natural thing is to think of the folk music that came from the 1960s,” Funke said, listing off songs including Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War,” Country Joe and the Fish’s “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag,” and Pete Seeger’s version of “We Shall Overcome,” all of which reached what Funke called an anthem status because of their subject nature and timing.

But like Kajikawa, he also noted these songs — which people often sang while they were taking part in one of the thousands of protest marches or demonstrations that took place in that decade — were nothing new and that protest music didn’t start with the 1960s nor did it end there.

Using the last song Funke mentioned as an example, Kajikawa said “We Shall Overcome” started out as a black spiritual that expressed the stress and pain associated with slavery. Before it resurfaced in the civil rights movement, he said, the song was adopted by labor organizers and sympathizers during the pro-union movements of the 1930s and 1940s.

“Songs have their own life and they take on their own tradition,” he said, explaining many people who write protest songs often pick a previous generation’s music and adjust it to fit their times. “There are some songs that have transcended the decades and never gone away.”

Another example of this tradition, he added, is 1931 union anthem “Which Side Are You On” that has since been covered by a number of musicians including Rebel Diaz, a hip-hop trio that re-mixed the song in 2007 and used it to challenge anti-immigration bills in Texas.

Continuing the tradition

Back in his hospital room, Valenti adjusts his guitar and starts playing a few bars of “Souplines,” a song he wrote that talks about the camaraderie people feel after having lost their savings, and in some cases their homes, during the financial crisis that erupted in 2008.

Behind what seems to be a happy-go-lucky message of the song’s verses – where Valenti sings about how “you meet such nice folks in the soup lines, they’re all having such a good time” and tries to paint a happy face on the people who are newly destitute and yet “still smiling through it all” – is a bit of sarcasm that tips the listener off that Valenti’s not exactly happy about the way things turned out. He’s a little more blunt with “Throw Them in Jail,” a song Valenti said during one performance was about “Wall Street bankers and what we should do with them.”

Valenti spent a few years playing music as a busker on the streets of Paris during the 1960s, and as a result became quite familiar with the protest songs of that era and how people reacted to them.

He took a break from songwriting to focus on his career, but found a calling when the financial crisis hit about five years ago and has since written about 70 songs, most of which have to do with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the financial collapse and other political themes.

“The trick to writing a good protest song is that it has to be both topical and universal,” he said, explaining that one song he wrote about Mitt Romney’s “47 percent” remark flopped because it was about a very specific instance in time, while songs like “Souplines” remain relevant because they’re about a broader topic people could relate to and will continue to relate to no matter what the era is.

Valenti said the Occupy movement is one of the biggest inspirations and audiences for his music, and along with several other musicians he has organized a few concerts to help the movement’s activists raise money and spread their message.

But he said that while today’s protest songs may have the same spirit and passion that came out of the 1960s, they aren’t nearly as much of a part of popular culture as the protest songs he listened to while growing up.

He said one of the biggest reasons for this is the number of independent radio stations that played protest or political songs has decreased significantly since the 1960s.

To make matters worse, Valenti said, these stations have been replaced with corporate, commercial music radio stations that seem to be focused on playing pop music more than anything else.

“The music industry isn’t super-interested in playing political music,” said Kajikawa, who agreed with Valenti’s arguments about the rise of commercial radio stations.

But he also said the Internet has created a place where people can listen to and share music, and that makes today’s artists less reliant on the radio as a means to get their messages out.

He sees the development of this new medium as just part of the evolution protest and political music has made that will continue for decades to come.