A honcho in winter with more tales to tell

Published 12:00 am Sunday, December 29, 2013

- A honcho in winter with more tales to tell

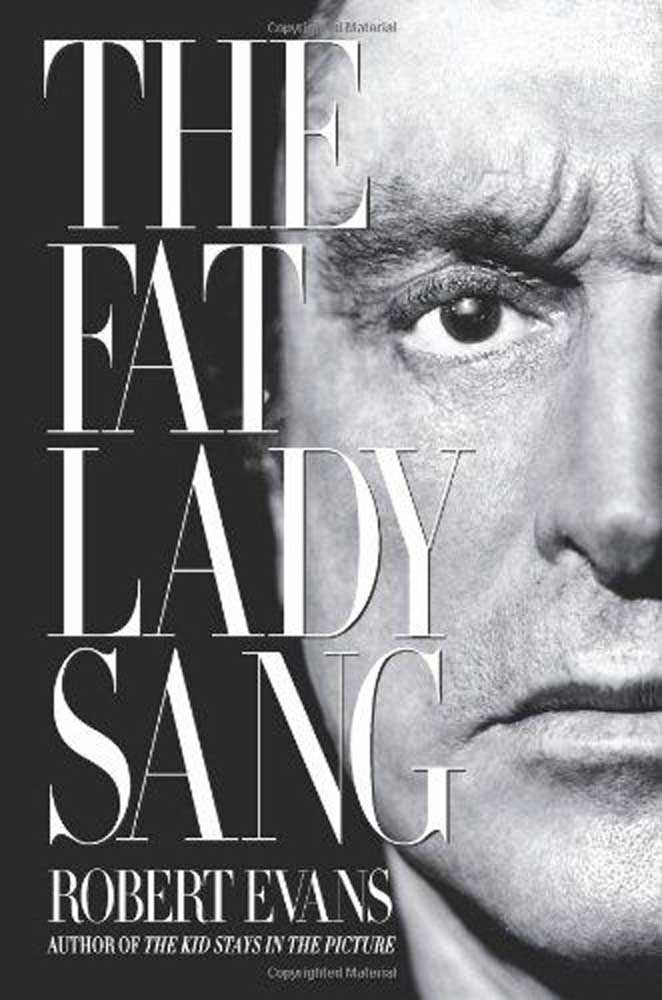

“The Fat Lady Sang” by Robert Evans (It Books, 231 pgs., $17.99)

In 1998, Robert Evans, the least bashful producer in Hollywood, suffered three strokes in rapid succession. Their combined effects were so debilitating that it was not clear whether Evans would ever walk, talk or chase women again. But as his new memoir, “The Fat Lady Sang,” makes clear, at least Evans’ capacity for bragging and self-promotion remained mercifully unimpaired. He is still able to say “Wham, bam, there I am” in as many ways as this stubbornly upbeat book will allow.

“The Fat Lady Sang” would not exist were it not for Evans’ four-star memoir, “The Kid Stays in the Picture.” Published in 1994, it has earned its place in Hollywood history because of its author’s endless supply of gossipy, embarrassing stories and because of the high drama of his movie career. He began in front of the camera and parlayed his good looks into life as a ladies’ man. He got lucky with his first foray into producing. He was head of production at Paramount Pictures during the early 1970s, a great time to be there. “The Godfather” and “Rosemary’s Baby” happened on his watch. In the midst of that, his marriage to Ali MacGraw unraveled as publicly as possible.

In the 1980s, he hit the skids after being convicted of cocaine trafficking and dragged into a murder trial. He could easily have slid into obscurity after that, but he remained too well connected, visible and vain. For a satirical glimpse of Evans’ personal style, watch Dustin Hoffman produce a war as if it were a movie in “Wag the Dog,” and get a load of that wardrobe.

“The Kid Stays in the Picture” had great stories to tell, and a sharp, slangy narrative voice that worked well on the page, even better when it was heard on the audiobook version. It became an interesting if stilted documentary, since Evans refused to be filmed for the story of his own life. And it made him a person of interest to younger readers who may have known nothing about him before. But it was not a book that cried out for a sequel.

Using the strokes as a strange form of good luck, “The Fat Lady Sang” crosscuts between the fears of the debilitated Evans (who is now 83) and the glory days that occurred long before his 1998 medical calamity. The early stories are much more grating and less glamorous than anything in “The Kid Stays in the Picture,” perhaps because less trouble was taken to tame Evans’ native language. (About his early days as a bobby soxer’s dreamboat, now more popular than in earlier versions: “Them mobs of girls, busting through them ropes, grabbin’ and screamin’ for my autograph.”)

This book also includes a heavy dose of man talk, as conducted by Evans and buddies like Alain Delon, Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty. According to this book, it’s all about which women can be gotten into bed how quickly and whether they’re good looking enough to be worth it. It’s not hard to believe that Evans really thinks this way. But when he cites a talk with Beatty about which of them bagged the oldest “above-the-line star,” he seems to live in a world where men are lost in their memories, and status, sex and acquisitiveness are hopelessly confused.

The one truly dumbfounding story in “The Fat Lady Sang” is that of Evans’ decision to defy his doctors in a very big way. Under instructions to be very cautious about his health, he suddenly decided to marry the actress Catherine Oxenberg (who was more than 30 years his junior). He made his case by giving her a Jaguar and having her drive it to a jewelry store. And he intended to fly with her to Cap d’Antibes, France, from California, but reality set in: The flight would be too taxing. They wound up honeymooning in California. He wound up not being able to get out of the bathtub. The marriage was over before Oxenberg’s live-in companion, who had been gone for the weekend, came home.

Evans seems to have bounced back in the 15 years since he was stricken. And a new book by the author of “The Kid Stays in the Picture” is a natural attention getter, even if the Kid stopped being a kid a long time ago. But in the earlier book he did not need to emphasize every standing ovation that had brought him to tears. He didn’t end chapters with lines like “Thus began the greatest odyssey of my entire life” and “And thus began the most celebrated years of my entire career.” And he didn’t need to play back every bit of puffery that came his way, like “They’re putting you on a pedestal you deserve.”

He seems to have forgotten the value of understatement, which served him so well the first time around.