A man who shaped American literature

Published 12:00 am Sunday, February 16, 2014

- New York Times News Service

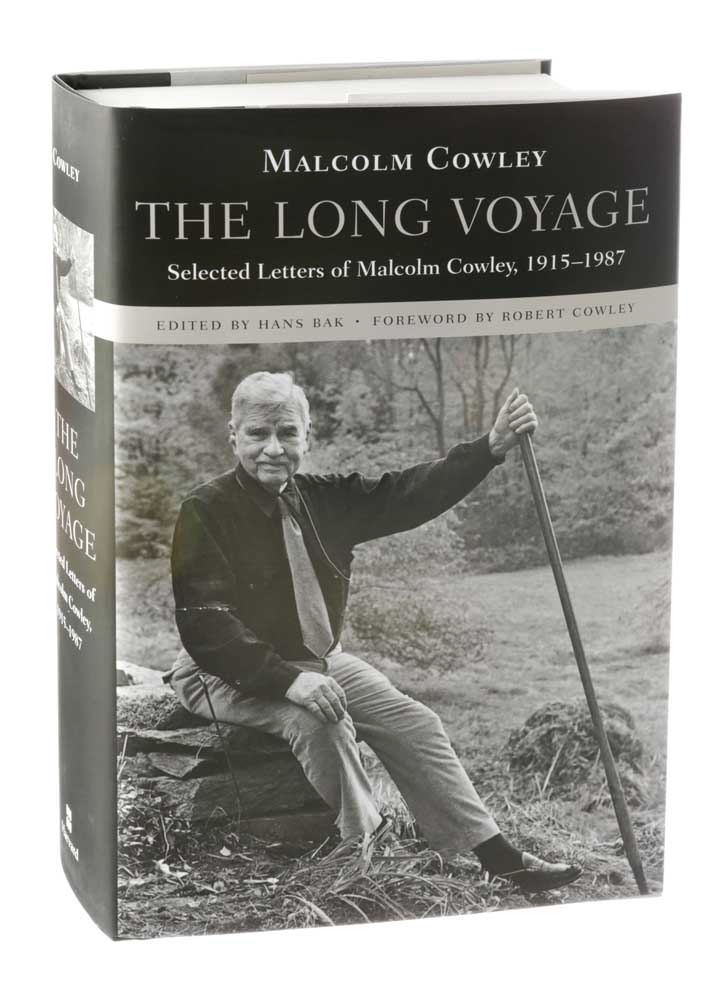

“The Long Voyage: Selected Letters of Malcolm Cowley, 1915-1987”Edited by Hans Bak (Harvard University Press, 800 pgs., $39.95)

When The Paris Review finally got around to interviewing Malcolm Cowley in 1982, when he was 84, among the first questions the magazine posed was this: “Do you regret not having concentrated more fully on your poetry?” Cowley said yes. His problem, he added, “was the essentially middle-class feeling that I had to support myself.”

Cowley (1898-1989) wasn’t a bad poet. His best verse is collected in a volume called “Blue Juniata” (1985). But we can be grateful that relative poverty mostly forced him to put poetry aside. He was more adept in almost every other arena: as a critic, historian, editor, journalist and translator, a “one-man assembly line,” in the words of a colleague. Cowley was also perhaps the greatest literary cross-pollinator of the 20th century. It’s impossible to imagine the American canon without him.

It’s tempting to fill the rest of this space, as if it were a puff pastry, with a creamy list of Cowley’s attainments. (Buzzfeed’s version would be “17 Surprising Things You Didn’t Know About Malcolm Cowley.”) I’ll try to winnow it.

A) William Faulkner’s novels were almost entirely out of print when Cowley went on a rescue mission, editing “The Portable Faulkner” (1946). Faulkner won the Nobel Prize four years later. “Damn you to hell anyway,” Faulkner wrote to him. “I didn’t know myself what I had tried to do, and how much I had succeeded.”

B) Cowley, who served in World War I and lived for two years in France, became the Boswell of his cohort, the chronicler of the so-called lost generation in his formidable book “Exile’s Return.”

C) As the literary editor of The New Republic during much of the 1930s, he was the instigator of a thousand useful feuds. Alfred Kazin called him “the last New Republic literary editor who dominated ‘the back of the book.’”

D) Cowley advised, and tended to the reputations of, many of his generation’s best writers, from Hemingway and Fitzgerald to Cummings and Hart Crane. (Cowley’s first wife, Peggy, was traveling with Crane when he committed suicide in 1932 by leaping from a steamship into the Gulf of Mexico.)

E) He rescued and championed the first edition of “Leaves of Grass,” free of Whitman’s many revisions, a version that was almost entirely unobtainable at the time. “It was the first edition,” Cowley observed, “that was the miracle.”

F) He was instrumental in the careers of Jack Kerouac, John Cheever and Ken Kesey. Cowley persuaded Viking to accept “On the Road” after many publishers had turned it down. He worked to get Kerouac, who was broke, financial support. Kerouac wrote to Cowley about one of his interventions: “It was like a lamp suddenly being lit in the darkness, like that. It was a selfless gift of kindness.”

Cowley’s best letters — they are alternately frisky, warm, pushy and ruminative — are collected now in “The Long Voyage,” edited by Hans Bak, a Dutch professor of American literature. Cowley liked composing letters; he tossed them off in the morning, as mental warm-up exercises, before his real work commenced. Of the more than 25,000 of them extant, this plump volume presents about 500.

Many are to his childhood friend from Pittsburgh, the philosopher of language Kenneth Burke, and to his lifelong confidant Allen Tate. This volume also records his end of correspondences with Faulkner, Kerouac, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Dawn Powell, Lionel Trilling, Louise Bogan, Edmund Wilson and multiple others.

Consistently busy on a multitude of fronts, Cowley wrote letters that are grainy with gossip and ringing observations, almost from the beginning. In 1920, when he was all of 22, he advised Van Wyck Brooks on the freelance life: “When one writes for The Nation, one is pompous; one is arty for The Dial and economic for The New Republic.”

Here is his half-admiring assessment of how Randall Jarrell treated his fellow poets in his gonzo poetry reviews: “Why, if he whipped them with a whip soaked in brine, kicked them in the kidneys, held lighted matches to their sexual organs, he could scarcely cause them more pain.”

Cowley had a gift for tidy assessments. He found Kazin “strenuously on the make” (and told him to his face). Larry McMurtry, whom Cowley taught in the 1960s at Stanford, is described as a “wild young man from Texas, expert in pornography.” He advised Yaddo, the writers’ colony, to admit Sidney Hook, but not for too long. “You might find him an irritating guest to have all summer.”

Politics were Cowley’s intellectual big muddy. Like so many writers and intellectuals in the early 1930s, he was bewitched by radical politics. “For a brief time, the Communists were the only ones who seemed to have the answer,” he said. While he never joined the Communist Party, he admitted, “I was pretty crimson, or at least deep pink.”

He clung to a Stalinist position for far too long, until he was alone out on the tree branch. He was accused, by Wilson and others, of injecting politics too deeply into The New Republic’s literary pages. He was deposed as literary editor in 1940, and his radical dabbling would continue to haunt him.

Many of the best moments in these letters aren’t literary at all. Cowley wrote well about being alive. He noted that New York City is most bearable “to ragtime, cheek to cheek with a pretty stenographer.” Later, he would write: “There is a freemasonry of heavy drinkers, and it is rather a pleasure to belong to it.”