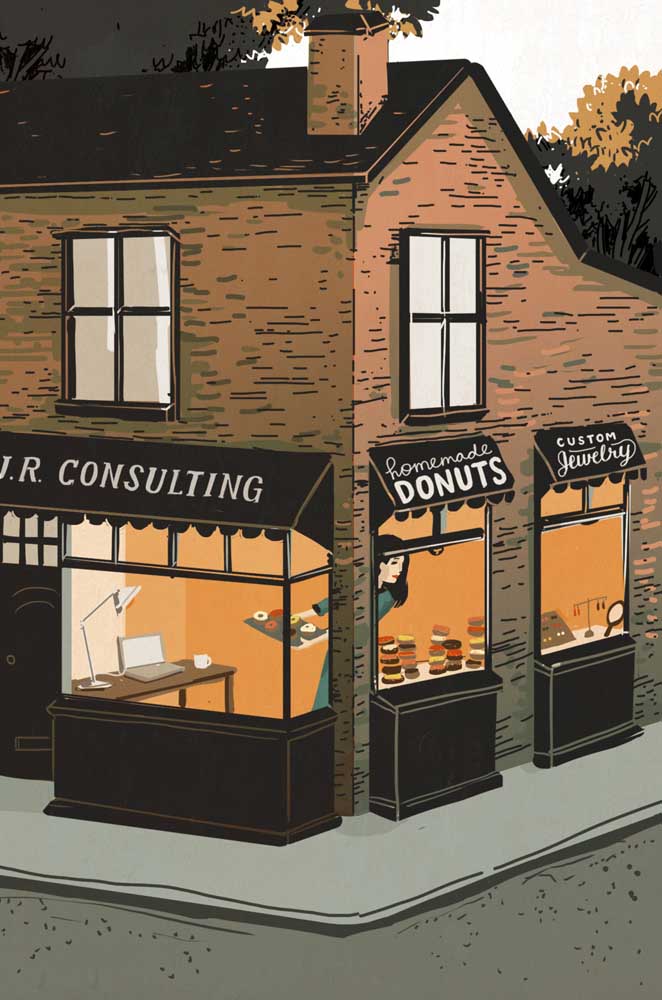

Needing financial security? Try a side business

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 30, 2014

- New York Times News Service illustration

In the height of the recession, as new rounds of layoffs were announced on what seemed like a daily basis, I was grappling with motherhood. Staring at my newborn daughter’s face, I felt overwhelmed with the responsibility. The job market only worsened my anxiety. What would we do if I were to suddenly lose my job, or if my husband were to lose his? How would we care for our child?

As a reporter working in a struggling industry, I always knew unexpected job loss was a possibility, but now, the stakes had never been higher. Being so financially vulnerable was unacceptable to me. And one day, as I was preparing to interview a businesswoman who made her living by selling cutting boards on Etsy.com, the handmade marketplace, I thought I had come upon a solution: I could have a side job making things to sell on the site.

By adding a second stream of income, I would no longer be entirely dependent on a single paycheck. As I explored the website to prepare questions for my interview, I discovered a section of calendars and planners. Some of them, like meal planning and budgeting sheets, looked like something I could create. What if I started an Etsy shop of my own, selling money planners based on my years of personal finance reporting? I could create workbooks based on different life goals, including having a baby and budgeting. What if I could become as successful as those Etsy sellers who crochet scarves and carve furniture?

I got to work as soon as I finished the article I was working on. Within two weeks, I had created my first money planner, which took readers through my best budgeting, saving and smart spending tips. It encouraged people to reflect on their big money goals and to come up with a personal definition of financial success. I enlisted a freelance illustrator to create a cover and inside illustrations for around $100. In addition to creating a PDF to sell as a digital file, I sent my planner to a printer to create a few dozen spiral-bound versions, at a total cost of about $300. My entire shop was off the ground for just $400 and a couple of weeks of work on weekends and evenings.

As soon as I listed that first product, I felt more in control of my life. I was an entrepreneur, not just an office worker. I felt a rush of pride every time I pulled up my shopfront on my computer screen.

Those good feelings were soon clouded by my lack of sales. My number of visitors hovered around 10 people a day, and none were buying. That’s when I decided I had to spend some serious time on marketing, and I started studying the advice of other creative entrepreneurs who sell on Etsy. I began pitching my shop to bloggers who write about motherhood, family life and money — my target audience. I hosted giveaways and wrote guest posts for those sites. My number of visitors slowly climbed, and so did my sales. I started earning about $200 a month from my shop.

That might not sound like much. But it felt extremely significant to me. That’s because I felt my new business was something that I could ramp up and turn into something even bigger if I ever had the time, desire or need to do so. In the meantime, an extra $200 a month came in pretty handy for the escalating baby-related costs.

My plans did not proceed without hiccups, of course. Few people bought my spiral-bound planners, so that investment ended up being largely a waste of money. My customers gravitated toward the digital versions, which are available immediately for download upon purchase. I made more adjustments after noticing that people often bought a few different types of planners at once. To meet that demand, I created “planner kits,” which came with discounts on bundles around a theme, like buying a home or starting a business.

As my business grew, so did my stress level. I was suddenly juggling my young daughter, a full-time job and my online shop. I worked on my planners whenever I could, which was primarily during nap time on the weekends and in the evenings after my daughter went to bed. The kind of business that it is — requiring a lot of upfront work creating the products but then very little as sales are made, since Etsy handles the payment collection and file downloads — made it possible for me to continue to fit the shop into my life.

Etsy charges me 20 cents for every product listing plus 3.5 percent of every sale, but that seems well worth the relative ease of running my shop. We soon added a son to our family, which increased my desire to create more financial security for my family, but made it harder to find the time to do so. I still build my shop when I can, which is usually when my children are asleep. (And thanks to Etsy, my sales get processed even when I am asleep.) My side business now brings in around $5,000 a year, and I figure I could double that if I carved out more time to work on it each week, to add more planners and do more marketing.

Like many side-business owners, I never want to leave my full-time job. Not only do I enjoy it, but I feel lucky to have a level of financial security and benefits that are hard to come by as a full-time entrepreneur. A lot of people feel the same way: The Young Entrepreneur Council reports that a third of millennials have a side business. On Elance, 30 percent of the freelancers also maintain full-time jobs. On Etsy, a quarter of sellers hold day jobs.

One of those millennials is Sydney Owen Williams, who handles marketing during the day for a sky diving center in Lake Elsinore, Calif., and in her off time coaches 20-somethings hunting for their first jobs. That income, she said, supplements her relatively low base salary at the sky diving center. Similarly, Chris Furin, now a full-time custom cake designer in the Washington area in his early 40s, started his business when he worked full time at his father’s deli, baking and designing the cakes at night. When the deli shut in 2011, he was able to start bringing in at least $3,000 a week on his orders. Febe Hernandez, a federal worker and jewelry maker in her early 60s, adds to her salary by holding trunk shows where she said she regularly pulled in $2,000. She plans to continue to expand her jewelry business when she retires from government.

Those kinds of hybrid careers are exactly what this new economy demands. People lucky enough to have a full-time job may never know for sure how long it will last. And having a backup plan in case it does disappear not only provides a safety net but for some a satisfying creative outlet.