Zoo animals and their discontents — diagnosed?

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 6, 2014

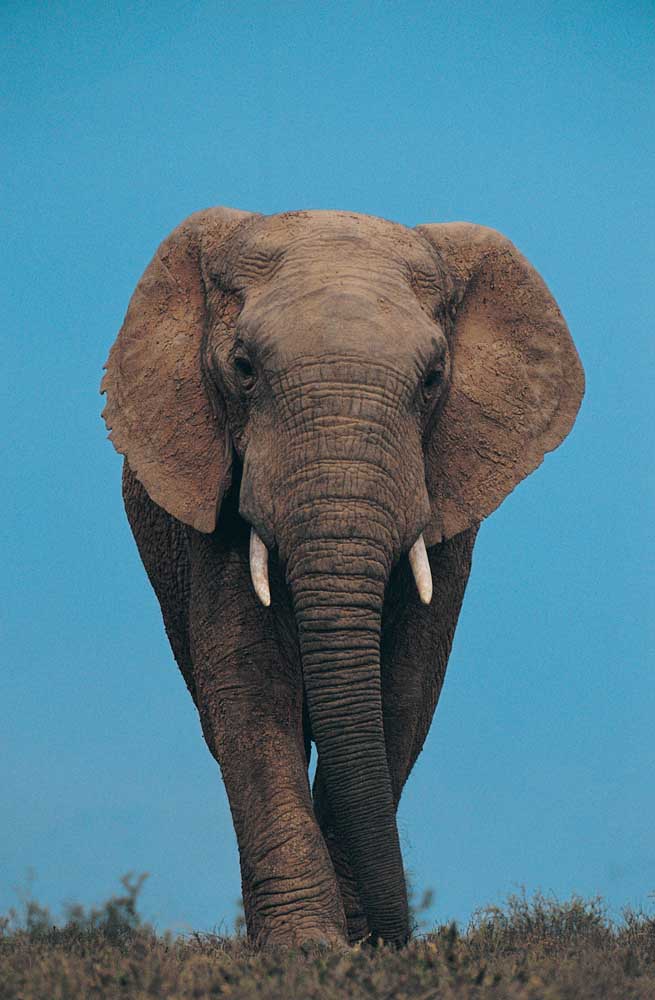

- Thinkstock photosJust like us? Yes, elephants can experience constipation, giraffes can be conditioned to like men again, and gibbons appear sad after another gibbon’s death, just to name a few actual cases. But can animals — not just pets, but other creatures, too — be diagnosed as actually, clinically depressed? Is Prozac an answer?

Dr. Vint Virga likes to arrive at a zoo several hours before it opens, when the sun is still in the trees and the lanes are quiet. Many of the animals haven’t yet slipped into their afternoon malaise, when they retreat, appearing to wait out the heat and the visitors and not do much of anything.

Virga likes to creep to the edge of their enclosures and watch. He chooses a spot and tries not to vary it, he says, “to give the animals a sense of control.” Sometimes he watches an animal for hours, hardly moving. That’s because what to an average zoo visitor looks like frolicking or restlessness looks to Virga like a lot more — looks, in fact, like a veritable Russian novel of truculence, joy, sociability, horniness, ire, melancholy and even humor.

The ability to interpret animal behavior, Virga says, is a function of temperament, curiosity and decades of practice. It is not, it turns out, especially easy. Do you know what it means when an elephant lowers her head and folds her trunk underneath it; or when a zebra wuffles, softly blowing air between her lips; or when a red fox screams, sounding disconcertingly like an infant?

Virga knows, because it is his job to know. He is a behaviorist, and what he does, expressed plainly, is see into the inner lives of animals. Most behaviorists are former animal trainers; some come from other fields entirely. Virga happens to be a veterinarian, very likely the only one in the country whose full-time job is tending to the psychological welfare of animals in captivity. He works with zoos across the United States and in Europe, and like most mental health professionals, he believes his patients possess vibrant emotional lives. His recent book is titled “The Soul of All Living Creatures.” What all of this means is that Virga has embraced notions that until recently were viewed in the scientific community as at best controversial and at worst nonsense.

The notion that animals think and feel may be rampant among pet owners, but it makes all kinds of scientific types uncomfortable. “If you ask my colleagues whether animals have emotions and thoughts,” says Philip Low, a prominent computational neuroscientist, “many will drop their voices to a whisper or simply change the subject. They don’t want to touch it.” Jaak Panksepp, a professor at Washington State University, has studied the emotional responses of rats. “Once, not very long ago,” he said, “you couldn’t even talk about these things with colleagues.”

That may be changing. A profusion of recent studies has shown animals to be far closer to us than we previously believed — it turns out that common shore crabs feel and remember pain and that zebra finches experience REM sleep. In the summer of 2012, an unprecedented document, masterminded by Low — “The Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness in Human and Nonhuman Animals” — was signed by a group of leading animal researchers in the presence of Stephen Hawking. It asserted that mammals, birds and other creatures like octopuses possess consciousness and, in all likelihood, emotions and self-awareness.

It is not the habit of researchers to speculate broadly about the implications of their work. “We’re on the same page in general, but not at all on the specifics,” said Panksepp, who was a signatory of the declaration. “As far as science is concerned, animal thought remains at the argumentative level.” Low admits that scientists have not even been able to agree on a working definition of consciousness.

Beyond the science

Though he follows the research, Virga, 56, is not a researcher; his convictions about animal individuality predate the recent science. And while the theories about animal cognition are fascinating to consider, they aren’t always germane to a behaviorist crouching behind a barn door amid a row of trash cans while being charged by a 700-pound takin — a hirsute Tibetan goat-antelope with a not-trivial set of horns — named Chopper.

Zoos contact Virga when animals develop difficulties that vets and keepers cannot address, and he is expected to produce tangible results. Often, the animals suffer from afflictions that haven’t been documented in the wild and appear uncomfortably close to our own: He has treated severely depressed snow leopards and phobic zebras.

“Scientists often say that we don’t know what animals feel because they can’t speak to us and can’t report their inner states,” Virga said. “But the thing is, they are reporting their inner states. We’re just not listening.”

A visit to the zoo

Last summer, I visited Roger Williams Park Zoo in Providence, Rhode Island, where Virga was about to begin his rounds. He lives nearby and has worked with the zoo for six years. On my first visit there, Virga and I found ourselves in the middle of a commotion. Keepers and other assorted personnel darted down the lanes with a look of disquiet. When Virga flagged one down, it turned out that the cause was an Asian elephant named Alice.

“You haven’t heard?” a keeper asked breathlessly. “Alice is blocked.” Alice was constipated, and the man brought us up to speed on how the elephant’s keepers and a veterinarian had spent hours administering enemas and Gatorade.

Here is the thing about people who work at zoos, by which I mean the people who actually work with animals. Nearly to a one, they like animals, and dote on them, and enjoy their company to an almost unseemly degree.

Still, there’s no denying the public qualms about the entire project of keeping our animal friends captive for education and profit. Much of the residue of mistrust that clings to the roughly 250 accredited zoos and aquariums in the United States stems from their less-than-picturesque past.

“Zoos have changed incredibly in the last 30 years,” says Mark Reed, the executive director of the Sedgwick County Zoo in Wichita, Kansas. “These days, moats and glass have replaced cages; there are education departments and conservation initiatives. And full-time vets, antibiotics and better diets have doubled and in some cases tripled animals’ life spans in captivity.”

But can improved conditions justify captivity? One case study turned out to be Virga’s patient Molly, an aoudad, more commonly known as a Barbary sheep. I met her in the enclosed barn where she spends nights. She had a short tawny coat and horns roughly the size and shape of large plantains. Molly had been a typical 7-year-old when she suddenly lost the use of her tail, a short appendage aoudads use to signal danger and bat away insects. The area under her immobile tail became vulnerable to infection, and before long the zoo staff made the decision to amputate. Shortly after, Molly began to exhibit increasingly alarming behaviors: She grew agitated and twitchy, she began to confine herself to three spots in the exhibit and she became frantic when a fly buzzed near her. In the absence of insects, she stood scanning the air for them, no longer interested in interacting with the other aoudads. More distressing, Molly refused to go inside the barn and wouldn’t allow the keepers to touch her.

Virga watched Molly for days, shot video of her with his tablet and spent nights replaying the footage on the monitor in his study. The initial plan was to direct her attention elsewhere, tempting her with items irresistible to most Barbary sheep: logs, cinnamon, endless treats. Molly ignored every overture. What troubled Virga was that he hadn’t been able to interrupt her behaviors, which signaled to him that Molly was experiencing something beyond ordinary fear.

“Fears can be unlearned, but phobias can’t,” he said. “Conditioning won’t work on a phobic animal.” So, reluctantly, Virga did what thousands of mental health professionals have done before — he prescribed Prozac. Within weeks, Molly began a gradual return to her preinjury self. Insects still sometimes made her frantic, but she no longer stood looking for them when they weren’t there. Virga repeated his efforts to redirect her attention away from the sources of her anxiety; this time, aided by the medication, she showed a more robust response.

Medicating the beast

Virga uses medication as a last resort. (Molly remains on Prozac, albeit a lower dose.) I asked him whether Molly’s distress didn’t, in a way, confirm her intelligence. In scanning for flies when there were none, Molly wasn’t responding to a stimulus. Instead, I wondered out loud, wasn’t she remembering insects from her past and anticipating them in her future, thereby demonstrating her capacity for memory and prediction? Virga grinned and nodded.

Virga claims he doesn’t play favorites, but he enjoys spending time with BaHee, an 11-year-old gibbon at Roger Williams, an awful lot. BaHee is something of a showman: He seems to genuinely enjoy contact with visitors and staff members, and in their presence he bounds along the fence and makes faces.

Virga began working with BaHee after Gloria, the female gibbon who shared his habitat, left. BaHee and Gloria were quite the (platonic) couple: His fur was black, hers was buff, and she played a chiding matronly figure to his teenage brat. The two small apes shared their space for three years in mostly affectionate equipoise.

In 2012, Gloria was in her early 30s and began to exhibit symptoms of a Parkinson’s-like illness. After she lost the use of her legs to tremors and routine movements became labored — and treatment proved unsuccessful — the zoo staff decided to euthanize her. Once Gloria was gone, BaHee withdrew. He ate less, moved less and sometimes refused to go on exhibit. Most striking, he lashed out and bared his teeth at Kelly Froio, his primary keeper, who took Gloria from the barn on that last day.

Virga believed that BaHee was clinically depressed. The cause was grief, which is the reason Virga didn’t pursue an aggressive course of treatment for the gibbon’s symptoms, instead prescribing “concern, patience and understanding.” The worst of the depression lasted three or four months, a span similar to the acute phase of human grief after the sudden death of a family member. By the summer of the next year, BaHee’s symptoms had mostly disappeared.

When I asked Kim Warren, another of his keepers, about the episode, she said: “BaHee was grieving. You could see it on his face.” Then she reconsidered. “I shouldn’t say that,” she said, choosing her words carefully, “because that’s anthropomorphism. I should say instead that BaHee was displaying withdrawal behaviors.”

Talking about feelings

Several staff members at Roger Williams told me, privately, that they felt uncomfortable talking about what their animals felt, though they were convinced that their animals experienced thoughts and emotions. At its worst, anthropomorphism, the fallacy of attributing human characteristics to nonhumans, leads us to imbue animals with our perceptions and motives, reducing the worldview of another species to a bush-league version of our own.

Yet avoiding anthropomorphism at all costs may be the main cause of the schism between scientists and the public in the debate about animal sentience. “Most reasonable people will be on the side of animals being sentient creatures despite the absence of conclusive evidence,” Panksepp told me. “But scientists tend to be skeptics. And, in this field, it pays to be a skeptic if you want to get your research funded.”

For a behaviorist at a zoo, striking a balance between hard science and drawing reasonable parallels between human and animal suffering may be the only avenue toward effectively treating patients. Virga told me that encountering misgivings about anthropomorphism once made him timid about expressing his convictions.

“But we get to a point in our careers when we say, ‘This is what I feel.’ And now my job is to prove it,” he said.

The debate between skeptics and believers, he says, is akin to arguments about religion, and he’s not eager to engage. “Sometimes a scientist will ask me, ‘What are your data points?’” he said. “But if we accept that animals are self-aware beings and have emotions, they are no longer data points. No amount of data points will explain identity.”

People watching at the zoo

If you’re already feeling irritable, watching people at a zoo may not improve your mood. During a trip Virga and I took to Central Park Zoo, a boy stood by the side of an aquarium, pointing, and yelled “SEA WIONS!” approximately 37 times in a row. On our way out, Virga and I watched a man charge a red panda with Kenyan-marathoner velocity and nearly bayonet the animal with a camcorder-and-zoom-lens combo of early-microwave-oven dimensions.

I saw the fallout of such photographic harassment when I visited Sukari, a 21-year-old Masai giraffe at Roger Williams who had developed a fear of men with large cameras. Weeks before she was bolting at the sight of a zoom, Sukari began refusing meals.

“Some days she would eat, others she wouldn’t, and she got picky about her food,” said Rachel McClung, one of Sukari’s keepers. “And then there was the licking.”

Sukari stood licking at her lips, oblivious to the other giraffes, who began to shy away from her. For hours at a time, she licked steel cables. She licked unremarkable white walls. She licked gates. Over the course of a few months, her weight dropped from 1,850 pounds to about 1,600. To make matters worse, she also began to avoid men in hats and trenchcoats, and after a while, she wanted no part of the public side of the yard.

Virga spent entire afternoons with Sukari, trying to get her to eat by offering different kinds of hay. He eased her closer to visitors and rewarded her each time with browse (leafy branches), her favorite food. Often he simply spent time with the giraffe and waited. Gradually, Sukari began to improve. Her weight rose, and the licking dropped off.

Virga knew that he wasn’t likely to cure her — she had been prone to anxiety throughout her life. It was her nature, he reasoned, just as there are people who are prone to anxiety. Yet the giraffe’s fear of cameras, and the remaining symptoms, continued to fade.

To feed Sukari, I had to walk up a steep staircase to a metal landing, just to be level with her head. Following McClung’s instructions, I offered her a branch covered with leaves, and she licked it clean with her long, pale tongue. Sukari chewed the leaves gamely, working her jaws with real gourmandise. And then her eye strayed toward the ceiling, and she quit chewing and slightly turned her head. No sound or movement had distracted her. For a span of some seconds, her eyes grew unfocused and an expression crossed her distracted face that could only be a passing thought. Or so it looked to me.

Before wrapping up that visit to Roger Williams, I looked in on Molly, the Barbary sheep. She happened to be standing on a rock, her horns back, looking like the proud mascot of a hedge fund. Just then, a group of visitors, young teenagers with Down syndrome, wandered into the exhibit. The adult with them explained about aoudads, and the teenagers, silenced by Molly’s proximity, looked at the animal with remarkable seriousness. Molly looked back.

“What is it thinking?” a girl asked, but the adult didn’t answer. Everyone stood looking, the teenagers at the aoudad and the aoudad at the teenagers, until Molly hopped down from the rock and darted away.