’Last Stories’: dead girls and the ‘ick’ in lovesick

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 13, 2014

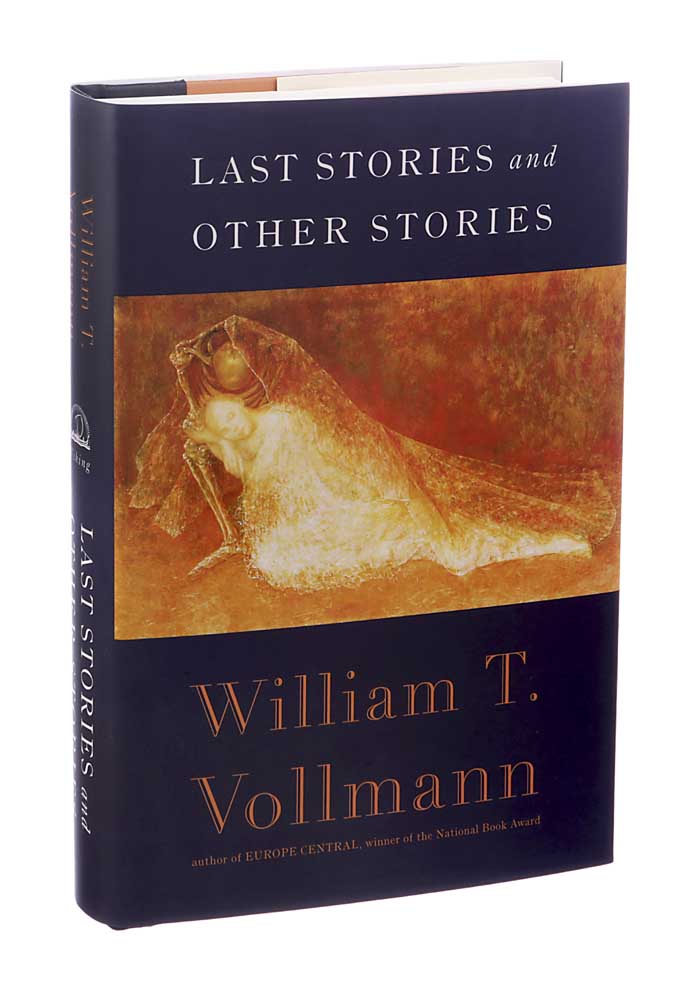

- Sonny Figueroa / New York Times News Service"Last Stories and Other Stories" by William T. Vollmann

“Last Stories and Other Stories”by William T. Vollmann (Viking, 677 pgs., $36)

William T. Vollmann is, as often as not, more interesting to read about than to read. His hobbies have included hookers, drugs, large-caliber pistols and tramping through war zones. He’s written a seven-volume treatise on violence. Yet he’s never been a Hunter S. Thompson manqué. There’s no gonzo coil in his DNA.

Vollmann wanders the globe like a man-child, it seems, or an outsider artist, gathering grim experience while remaining po-faced and curiously innocent. His sentences can be boring, but he himself rarely is.

Last year, out of the blue, he published a book of photographs of himself as a cross-dresser. He also wrote last year about getting his hands on his FBI file and discovering that the U.S. government thought he might have been the Unabomber. These sorts of things never happen to Michael Chabon.

Vollmann’s new book, “Last Stories and Other Stories,” is his first volume of fiction since “Europe Central” (2005), which won a National Book Award. Not that he’s been idle. In the meantime, he’s published several dense slabs of nonfiction, including books about poverty, train-hopping and Japanese Noh theater, and a somewhat less slablike book about Copernicus.

“Last Stories and Other Stories” is harrowing in the boredom it delivers, except for the bits, mostly toward the end, in which his male characters have slushy sex with rotting female corpses, some of them ghosts or vampires or supernatural beings of some other sort. (There’s the occasional delectable male carcass as well.)

The book becomes a necrophiliac dreamscape: weedy crotches, wormy mouth cavities, sour nipples that pop off in a lover’s mouth. A more descriptive title for this book, to borrow the name of the White Stripes album, would have been “Icky Thump.”

“There may well be nothing on earth (or under it) as delectable as a fresh young corpse with a waxy yellow complexion, sunken eyes, conspicuous ribs and the sweet odor of decay,” Vollmann rhapsodizes. “I was intoxicated by that odor! I fell in love with her.”

Vollmann’s fiction, in books like “Whores for Gloria” (1991), has often found its most condensed energy around the topic of sex, and that’s no different here. Getting it on with a corpse, in a way, seems like a natural extension of the author’s avowed interest in paying for sex. Like prostitutes, dead girls are a sure thing.

There are other things to say about “Last Stories” before we return to the topic of maggoty love. There’s the matter of this book’s title, and of its opening note to the reader, which declares: “This is my final book. Any subsequent productions bearing my name will have been composed by a ghost.”

This is Vollmann playing the trickster, and you should take this notice about as seriously as you took Stephen King’s retirement announcement in 2002. (King was 54 then; Vollmann is 54 now.) Viking will be publishing a new novel in Vollmann’s Seven Dreams series, about the settlement of North America, next summer.

Another thing to say about “Last Stories” is that it’s a phantasmagoric book, blending bits of Lovecraft and Dreiser, David Foster Wallace and Scheherazade, Poe and the Brothers Grimm, to mostly muddled effect. These stories pivot around the globe: Some are set in Mexico or Japan, others in America. A few are set in the present day, such as a story about an American war reporter returning to Sarajevo.

But Vollmann’s abiding interest here is in folklore, in tall tales, in ancient hatreds, and it’s a topic that plays to all of his weaknesses as a writer and few of his strengths. This book is humorless, indifferent, close to unendurable, a word pudding seemingly written on autopilot. Its plot movements appear to have been decided by throwing 10-sided dice.

Vollmann’s sentences are long and winding roads, as encrusted as Klimt paintings, and difficult to pull quotations from. But here’s the opening line of one story, “The White-Armed Lady”:

“Inside the tiny white house, he sat at the head of the table, listening to the sea gulls, his stare fettered from below by the white lace tablecloth, whose flower-whorled spiderweb knew how to trap his eyes, and occluded by the low-hanging lamp, whose candle never guttered within that scalloped breast of glass.”

“Last Stories” is an anthology of lines like this one, so suffocating (as Clive James once put it about a book about Leonid Brezhnev) that, if read in open air, they will make birds fall stunned from the sky. Vollmann doesn’t lash his research and his sentences into tight bundles, as he does in the best sections of “Europe Central” and the Seven Dreams saga.

The necromancy, and the necrophilia, that creep into “Last Stories” are unsettling, but here Vollmann seems alert, committed to his material. His antennae are erect. His verbs suddenly aren’t planted an acre away from his nouns.

Much of this material is difficult if not impossible to repeat here (there’s hot wraith-on-wraith action), but this passage, from a story titled “When We Were Seventeen,” gets at the tone of several of these stories.

“I’d very carefully brush the ants and dirt off your bones. I’d get in between your ribs and clean with a child’s toothbrush. And while I did that, I’d be singing to you, songs from when we were 17. I’d clean out your eyesockets with cotton swabs, very very gently, in case there’s anything left, and I’d comb your hair — you still have some. I’d comb it straight down your backbone. I’d brush your teeth for you, and I’d kiss you where you used to have a mouth.”

You come to realize that “Last Stories” builds to a suite of love stories, intended not to shock the unshockable but to trace the far reaches of this author’s obsessions with sex and death.

“Who are you, skull?” Vollmann asks in one of these stories, like Hamlet studying what’s left of Yorick. “Whom did you love?”