Skateboarder’s lament ponders change in U.S.

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 20, 2014

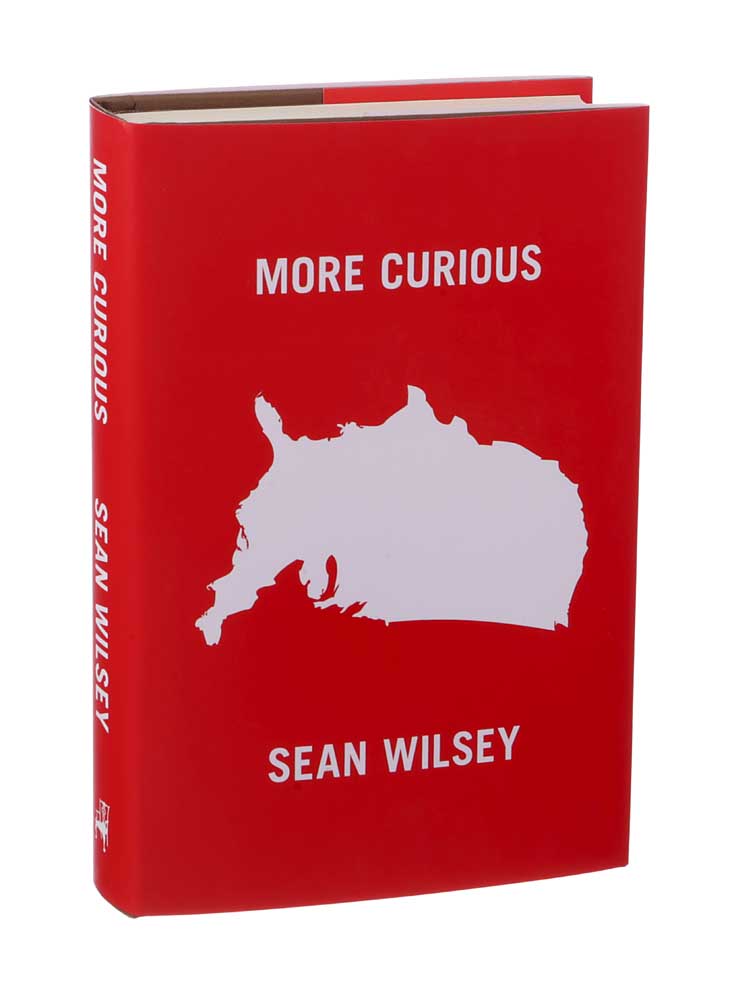

- Sonny Figueroa / New York Times News Service"More Curious" by Sean Wilsey

“More Curious”by Sean Wilsey (McSweeney’s, 342 pgs., $22)

Growing up in San Francisco, the writer Sean Wilsey was an ardent skateboarder. He says he never went anywhere without his board. He skated in his room when it rained. He loved the “kickflips” and “heelflips” of the pioneer skater Rodney Mullen — “tiny, precise things that seemed like the work of Swiss watchmakers, with perfect balance and total concentration” — and worshipped the “grace and style and imagination” of the street skater Natas Kaupas, who could jump onto a wall, “riding it like a wave,” moving from the horizontal to the vertical with supernatural ease, defying the laws of physics.

In his funny-tender-raucous epic of a memoir “Oh the Glory of It All” (2005), Wilsey demonstrated that as a writer he can be as nimble — and as inventive — as a gifted skateboarder, and his new collection of essays, “More Curious,” similarly showcases his talent with words. Like Dave Eggers (whom he has worked with at McSweeney’s) and David Foster Wallace (a onetime neighbor, who makes a brief appearance in this volume), Wilsey can write in a range of emotional octaves, moving from the comic to the philosophical to the street-wise with ease, while putting body language on his prose to give the reader an almost synesthetic sense of what he’s saying.

The pieces here were originally written for publications such as The London Review of Books, National Geographic, GQ and The New York Times Magazine. But while the book ranges over a wide array of subjects (from a profile of the restaurateur Danny Meyer, to an account of a cross-country drive in a 1960 Chevy truck, to an essay about Sept. 11), it has more coherence than many anthologies of this kind. This is partly because of Wilsey’s distinctive voice threading through its pages, partly because most of the articles articulate, in one way or another, his view of contemporary America — a place defined by the velocity with which it changes, a country capable of the miraculous (putting a man on the moon) but now reeling from what Wilsey describes as an “end-times vibe” of rabid consumption and blingy consumerism.

The opening and closing chapters are about Marfa, Texas: a high-desert town founded in the 1880s as a railroad stop and, by one account, named after a minor character in “The Brothers Karamazov,” which a railway overseer’s wife was reportedly reading at the time.

Wilsey began visiting regularly in the summer of 1996, when his girlfriend (and later, wife), Daphne Beal, was a reporter for a local weekly. He describes it, back then, as “a hardscrabble ranching community,” 60 miles north of the Mexican border, in “one of the least populated sections of the contiguous United States,” a place so isolated that “if you laid out the Hawaiian archipelago, and the deep ocean channels that divide it, on the road between Marfa and the East Texas of strip shopping and George Bush Jr., you’d still have 100 miles of blank highway stretching away in front of you.”

There was so little to do there, he writes, that people would “drive 100 miles just to have something to do, the way the rest of the country goes to the mall.”

The well-known Minimalist artist Donald Judd moved to Marfa in the 1970s, having acquired a series of properties that he used for large-scale installations of his work, and to exhibit the work of artists he admired. Since his death in 1994, the town — with a big assist from the Chinati Foundation, a contemporary-art museum founded by Judd that sponsors symposiums, internships and artist-in-residence programs — became an increasingly potent magnet for artists and art tourists.

By 2012, this little frontier town had become what Vanity Fair called a “Lone Star Bohemia.” There was a film festival in 2011 featuring 1970s and early ’80s “No Wave films alongside banned and sexually explicit work” by Larry Clark, Wilsey writes, along with a concert by a local punk band called Solid Waste. A “bookstore/wine bar” had opened on the main street, and a lot of what one local calls “those writer people” have taken up residence.

As Wilsey observes in another essay, skateboarding has undergone a similar sort of transformation: What had been in the ’70s and ’80s the purview of outsiders, “parentless, rejected, lonely” teenagers, became big business, he suggests, with the high-profile (and lucrative) career of Tony Hawk, “the first human being for whom skateboarding was a career instead of a last resort or a refuge.” Skaters became athletes, he says, and as videos went viral, the sport became more and more about tricks and stunts, instead of the artful navigation of city streets with speed and flow.

Perhaps the loss Wilsey mourns the most in American life is the country’s radical downsizing of its space program (a sentiment shared, apparently, with Eggers, in light of that author’s last novel). In an emotional outburst, after a visit to NASA, Wilsey exclaims: “When people think the best thing we’ve ever done as a nation — put a man on the moon — is a con, or a waste, and not a wonder — that is when we know we are truly lost.”

Some readers may find such hyperbole (is putting a man on the moon really the best thing the United States has ever done?) annoying. But Wilsey is able here to convey his feelings earnestly — be they amazement or anger, idealism or impatience — with the same vividness and immediacy he brings to his descriptions of people, places and things.

He conjures the Paleozoic landscape of the desert surrounding Marfa; the courtly personality of his dog, Charlie (“He’d’ve opened doors if he could have. ‘After you,’ Charlie always seemed to be saying.”); the surreal experience that is zero gravity (“Direction doesn’t matter when you’re weightless. Up and down are no longer markers. I suddenly understood how in space there is only everywhere”).

As for soccer, he writes that “the world of the World Cup is the world I want to live in.” In this world: “G.D.P. is meaningless. China is a nonentity. America has always lost.”

In one passage, he declares: “I cannot resist the pageantry and high-mindedness, the apolitical display of national characteristics, the revelation of deep human flaws and unexpected greatness, the fact that entire nations walk off the job or wake up at 3 a.m. to watch men kick a ball.”

“What is soccer,” he asks, “if not everything that religion should be? Universal yet particular, the source of an infinitely renewable supply of hope, occasionally miraculous, and governed by simple, uncontradictory rules (‘Laws,’ officially) that everyone can follow.”

Wilsey’s musings on the sport will doubtless resonate with readers going into World Cup withdrawal after last Sunday’s final: “Every four years,” he writes, “the joy of being one of the couple billion people watching 32 countries abide by 17 rules fills me with the conviction, perhaps ignorant, but like many ignorant convictions, fiercely held, that soccer can unite the world.”