A magical finale to a fun trilogy

Published 12:00 am Sunday, August 10, 2014

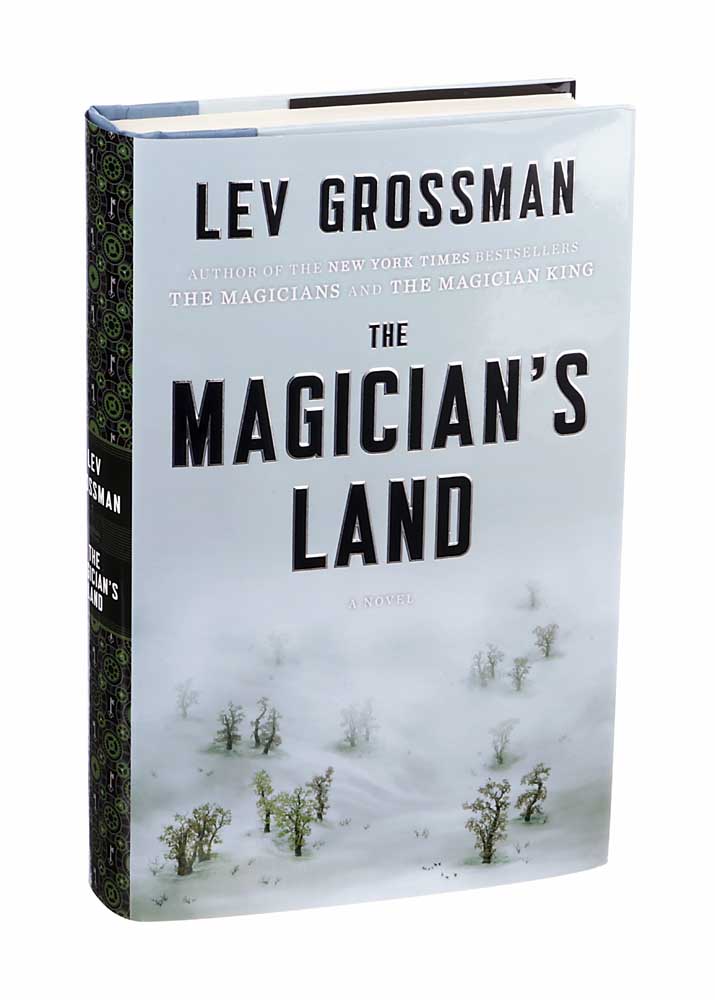

- Sonny Figueroa / New York Times News Service"The Magicians Land" by Lev Grossman

“The Magician’s Land”by Lev Grossman (Viking, 401 pgs., $27.95)

Toward the end of “The Magician’s Land,” the final volume of Lev Grossman’s wonderful trilogy for grown-ups, Julia and Quentin, both 30-ish, visit a magic garden whose plants are expressions of human emotions. The garden is in Fillory, the Narnia-like world that appeared in a series of books that they loved as children and that, thrillingly, turned out actually to exist.

Trending

“This is a feeling that you had, Quentin,” Julia explains, pointing out a delicate little shrub struggling for life. “This is how you felt when you were 8 years old, and you opened one of the Fillory books for the first time, and you felt awe and joy and hope and longing all at once.”

Out here in the real world, the yearning of some readers to experience that same heady feeling has lately been the subject of a spicy literary debate over what reading is for, pleasure or intellectual enrichment, and whether this should be a binary question at all. The issue, roughly, is if it is possible to be a serious citizen and still admire purportedly nonserious books: young adult novels, fantasy, genre fiction, books with compulsively interesting plots. Even Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Goldfinch” has been drawn in, pronounced by the critic James Wood to be too childishly and smoothly entertaining — more Krispy Kreme, perhaps, than mille-feuille.

“The rapture with which this novel has been received,” Wood told Vanity Fair, “is further proof of the infantilization of our literary culture: a world in which adults go around reading ‘Harry Potter.’”

Oh, dear. I am the sort of adult who goes around reading “Harry Potter.” And so, too, is Grossman, who has declared his fondness for “sparring with other books” in his writing. His characters are steeped in stories such as “The Lord of the Rings” and its many near and distant relatives. They are familiar to the point of self-consciousness, as are so many millennials, with the works of J.K. Rowling. How should they refer to nonmagical people, they wonder: Civilians? Muggles? Mundanes?

The story so far

“The Magicians,” the first book in the series, opens when a young man named Quentin Coldwater — like Harry Potter (but not really like Harry Potter at all) — discovers a world of magic in and around our own, and learns he has a great talent as a magician. An oversmart, overachieving Brooklyn high school senior, Quentin shows up for his Princeton interview at an alumnus’ house, only to find the college admissions process even more unpleasant than he supposed.

Trending

The interviewer has dropped dead. One of the paramedics who arrives on the scene does not appear to be a real paramedic. An envelope with Quentin’s name on it seems to contain a lost book from the Fillory series. And then Quentin is sucked into a hidden portal leading from Brooklyn to Brakebills College for Magical Pedagogy, the boarding school that is like, but not really like, Hogwarts.

The Brakebills students are freakishly intelligent and the school excitingly rigorous. In one of many terrific scenes in a series full of them, Quentin takes an entrance exam requiring him, among other things, to invent a new language, translate a passage from “The Tempest” into it, explain its grammar and orthography, describe “the made-up geography and culture and society of the made-up country where his made-up language was so fluently spoken” and then translate the passage back into English using the rules he has just made up. The reading-comprehension question vanishes even as he reads it, and all around him, students are vanishing, too, whisked off the premises for failing, midtest.

The first book takes us through Quentin’s years at Brakebills, where the students have sex, get drunk, go off the rails, talk trash and learn that “even the simplest spell had to be modified and tweaked and inflected to agree with the time of day, the phase of the moon, the intention and purpose and precise circumstances of its casting, and a hundred other factors.” They also dabble in esoteric and dangerous magic in scenes that evoke the lusciously overheated atmosphere of Tartt’s “Secret History.” Then they graduate, and the action for the rest of the series switches back and forth among Brakebills; the world outside, which carries some pretty heavy magic of its own; and the world of Fillory, which they find to be far darker and more complicated than they had thought.

Whimsy and darkness

In Grossman’s prodigious imagination, Fillory, like magic itself, is equal parts whimsy and darkness, coziness and danger, populated by the wondrous and the weird. It is (this is one of its whimsical traits) flat and held up by a giant stack of turtles, with turtles all the way down, allowing Grossman to perform the neat trick of alluding to both Dr. Seuss and Bertrand Russell in one fell swoop.

If you loved “The Chronicles of Narnia” as a child, and particularly if your love was later contaminated by the realization that C.S. Lewis had sneaked a stern religious allegory into his box of delights, you will be pleased by how Grossman has made the real Fillory diverge from the twee fictional one, revealing it to be nuanced, morally complex and nasty in a way that, to be frank, might have benefited Narnia. Let’s put it this way: Martin Chatwin, one of the children in the Fillory stories, is a piece of work and he is no Peter Pevensie.

“The Magician’s Land” finds Quentin out of his 20s and at loose ends, having been banished at the end of the second book, “The Magician King,” from Fillory, where he at least got to be king for a while. He takes a dubious magical heist job with some unsavory characters in New Jersey, mourns the loss of his girlfriend, Alice, who is something more horrible than dead (and also more horrible than a vampire, for the record); and sets about casting a spell alluded to in the book’s title. There are some thrilling digressive set pieces involving the strange adventures of other characters, a specialty of Grossman’s. Meanwhile, in Fillory, time is folding into itself; the end is near.

Grossman is usually a subtle, sophisticated writer, though, for some reason, he seems to have altered his tone in parts of “The Magician’s Land,” using too much narration with too much broish language. A Fillorian monster is a “scary-looking bastard”; some other creatures are “uncanny as hell.” But this is a quibble. If the Narnia books were like catnip for a certain kind of kid, these books are like crack for a certain kind of adult. By the end, after some truly wondrous scenes that have to do with the dawn (and the end) of existence, ricocheting back and forth between the extraordinary and the quotidian, you feel that breathless, stay-up-all-night, thrumming excitement that you, too, experienced as a child, and that you felt all over again when you first opened up “The Magicians” and fell headlong into Grossman’s world.

Brakebills graduates can have a hard time adjusting to life outside, though some distract themselves by lazily meddling in world affairs (e.g., the election of 2000). Readers of Grossman’s mesmerizing trilogy might experience the same kind of withdrawal upon finishing “The Magician’s Land.” Short of wishing that a fourth book could suddenly appear by magic, there’s not much we can do about it.