Dangerous bacteria spreads beyond hospitals

Published 12:00 am Sunday, November 9, 2014

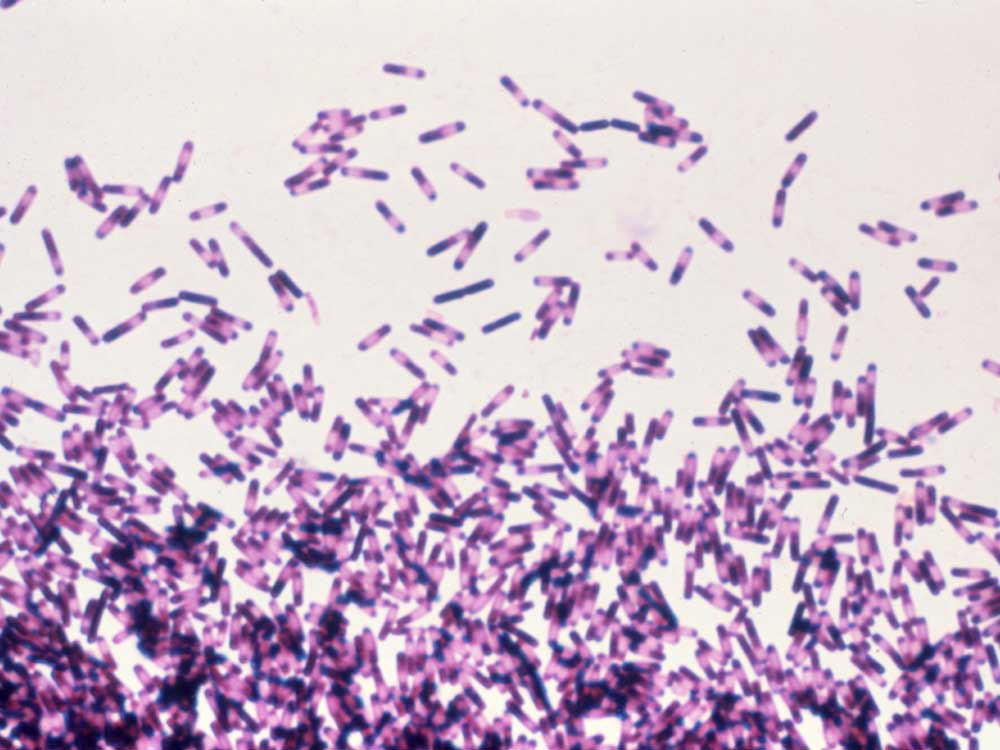

- Sanofi Pasteur / Submitted photoClostridium difficile impression smear. C. difficile is a spore forming bacteria which can be part of the normal intestinal flora in as many as 50% of children under age two, and less frequently in individuals over two years of age. C. difficile is the major cause of pseudomembranous colitis and antibiotic associated diarrhea.

Over the past decade, Clostridium difficile has emerged as the single most common hospital-acquired infection in the U.S., affecting more than 330,000 patients a year and causing 14,000 deaths. But infectious disease specialists have recently identified a dramatic and surprising shift in the transmission patterns of the bacteria.

Surveillance conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other health researchers suggests that up to half of C. diff infections now may be happening out in the community and among people previously thought to be at low risk.

“About 20 years ago it was thought that C. diff only happens in older people in the hospital who get multiple antibiotics,” said Dr. Sahil Khanna, a gastroenterologist with the Mayo Clinic. “But in the last few years, clinicians have been seeing that C. diff also happens outside the hospital.”

In response to a sudden rise in cases, in 2009 the CDC began tracking laboratory testing for C. diff in selected counties across 10 states, including Oregon. Out of more than 10,000 infections identified in 2009-10, nearly a third happened outside the hospital.

Surveillance in Deschutes and Klamath counties from 2009 through 2014 found about 52 percent of C. diff infections were community-acquired. Most cases occurred in individuals 75 or older, but infections were found in every age group, including children.

C. diff infections occur when someone ingests spores of the bacteria, which then germinate in the colon. Generally, spores are held in check by the normal, healthy bacteria in the digestive system. But when that healthy bacteria is killed off by antibiotic use or other changes, the spores are able to germinate and begin releasing toxins that can cause persistent diarrhea.

That fecal matter contains spores that can contaminate hospital rooms or be passed on by caregivers. And because spores can survive up to five months on surfaces and are impervious to many common cleaning agents, C. diff can spread quickly and easily through a health care facility.

But while hospital C. diff infections were almost exclusively linked to the use of antibiotics, in the community setting a substantial portion of patients had no reported antibiotic use. Nationwide, 36 percent of infected patients did not take any antibiotics in the 12 weeks prior to their infection, including 22 percent of those in Oregon.

Khanna and his Mayo colleagues found similar results analyzing data in Olmsted County, Minnesota, where medical records for all county residents are linked in an electronic database. There, about 40 percent of C. diff cases were community acquired, and only 78 percent of those reported any antibiotic use.

“So 20 percent of people who get C. diff in the (community) are not exposed to antibiotics,” Khanna said. “So why did they get C. diff?”

Khanna suggested a number of factors may be in play in the community setting. Many of those infected had contact with someone who had recently been released from the hospital or were caring for a patient with C. diff. Spores have also been identified in water sources and in meat processing plants, suggesting an environmental source of infections.

And there are some studies that suggest the use of proton pump inhibitors, a class of stomach acid medications such as Nexium or Prilosec, may increase the risk of C. diff. The link remains controversial, although there was enough evidence for the Food and Drug Administration to add a warning to the acid reducers’ medication label saying they can cause C. diff.

The researchers were also surprised to see that 40 percent of patients who acquired C. diff in the community needed to be hospitalized, and that those who did not take any antibiotics had a higher risk of hospitalization than those who did.

Transmission patterns

To dig deeper into the community infection patterns, the CDC researchers interviewed a portion of those who had gotten infected without a hospital stay.

“The majority of them had a doctor’s office visit or a dentist’s office visit, so it’s very unclear to us at this point where those patients acquired the C. difficile spores,” said Dr. Fernanda Lessa, a CDC epidemiologist. “Was it out in the community or was it an exposure in an outpatient setting?”

The CDC also compared the types of C. diff strains circulating in hospital and community settings. They wanted to see whether the C. diff strains circulating in the community were predominately the NAP7 or NAP8 strains that have been found in contaminated food or water, or the more virulent NAP1 strain that has been primarily responsible for hospital outbreaks.

“What we saw is that those NAP7/8 that were commonly isolated from animals and food items, they are not so common in the community. They were less than 4 percent of our strain types,” Lessa said. “The strain distribution overall is the same between the health care and community setting.”

That also suggests it’s unlikely that transmission in the community is a completely separate process from hospital transmission. Patients may pick up the infection in the hospital and then transfer to someone else out in the community. Estimates suggest up to 5 percent of all individuals are colonized with C. diff, but won’t experience symptoms unless they take antibiotics. According to the CDC, half of patients who develop an active C. diff case in the hospital likely brought that infection in with them. It was only when they received antibiotics after surgery or during treatment that the spores could germinate and cause symptoms.

Last year, a team from Oxford University used whole genome sequencing to see how C. diff was being spread through a single hospital in England over a three-year period. They found that less than 20 percent of infections were likely to have been passed on from other hospital patients. In fact they found that 45 percent of samples were genetically distinct from all previously tested samples. That suggests that patients in the community setting are picking up C. diff infections from a wide variety of sources.

Nightmare for patients

Karen, a 67-year-old Bend woman who asked to be identified only by her first name, developed an infection and abscess after a particularly rough dental visit earlier this year. Prescribed clindamycin, one of a handful of antibiotics that have been linked to a higher risk of C. diff, she endured six weeks of stomach cramps and persistent diarrhea before being tested for and diagnosed with C. diff.

She had never even heard of the condition before, yet soon learned that both her daughter and her sister had also had it.

Unable to shake the infection, she sought help from Dr. Glenn Koteen, a Bend gastroenterologist who prescribed 10 days of a targeted antibiotic, as well as yogurt and probiotics, which have been shown to help maintain healthy bacteria in the digestive system. But several days after she took her last dose, the symptoms returned.

This time, Koteen prescribed a longer course of antibiotics, tapering from four pills a day to one over a month’s time. She finished her last dose in late October.

“I’m feeling fine but I’m supporting Nancy’s Yogurt. I have a yogurt at every meal,” she said. “It angers me because it could have been prevented. Education would have helped a lot, not only me, but the physicians and the dentists, too.”

Koteen said he recommends anyone taking antibiotics also consume yogurt and probiotics to avoid creating conditions in which C. diff can take hold, and said doctors and dentists need to be more judicious with the antibiotics that have been linked to infection.

“We need to bring awareness to dentists to try to minimize clindamycin if they can, and to look for this the moment the patient says they have diarrhea,” he said. “Prophylactic preventive methods might be effective also.”

While specific antibiotics are effective at getting the infection under control, about one in five patients will experience a recurrent infection, and with each subsequent infection the risk of recurrence increases.

“If you get C. diff one time, it’s about 20 percent. Twice, it’s about 40 percent, and three times it’s about 60 percent,” Khanna said.

Another of Koteen’s patients, Barbara, 69, had surgery for diverticulitis in November 2013 and then started showing symptoms of C. diff in January. Ten months later, after multiple courses of antibiotics, she has still not fully recovered.

“I still get a little bit of the cramping. The diarrhea, some days it’s horrible, I wake up and I’m a mess. Other days, there’s nothing,” she said. “Personally, I don’t feel like it’s totally gone.”

The FDA has approved antibiotics specifically to treat C. diff, and medications approved for other conditions have shown to be effective when used off-label to treat infections. A two-week course of the antibiotic Vancomycin, for example, can cost upwards of $1,000 and not all drug plans will cover the cost.

More recently, clinicians have been treating persistent or recurrent C. diff by transplanting fecal matter from a healthy individual. That can restore the supply of healthy bacteria in the gut, allowing the body to clear the C. diff infection.

“It’s probably 95 percent effective, but it’s a mess and it’s expensive,” Koteen said.

Transplants were traditionally done by straining and diluting donated fecal matter, then delivering it to the patient’s colon either by endoscopy, colonoscopy or enema. More recently, doctors have been experimenting with putting freeze-dried fecal matter into a pill. Patients have to swallow 30 capsules over a two-day period.

“There’s the ‘eww’ factor,” Koteen said. “But the patients accept it extremely readily because they’re so debilitated and so sick, they’ll try anything.”

Change in strategy

The emergence of C. diff as a community-acquired infection may mean that public health efforts to battle the infection have to change as well. Hospitals have strict protocols for handling C. diff cases that include isolating the patient, using gloves and gowns when providing care, and cleaning the patient’s room with bleach after discharge. Coupled with more judicious use of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors, hospitals have been able to slow the rapid growth of C. diff infections that occurred since 2000.

But it’s unclear whether that will be enough to halt its spread beyond the hospital walls. Clinicians are now advising patients to take more precautions at home after a C. diff infection, including frequent hand washing, regular cleaning of household surfaces with diluted bleach and, if possible, not sharing a bathroom with other household residents.

Oregon recently implemented new rules requiring health care facilities to tell the receiving hospital or nursing home when they are transferring a patient with a C. diff infection so they can implement the proper infection-control protocols.

“My hypothesis is there wasn’t good enough communication, not only between facilities, but even within them,” said Zintars Beldavs, director of the health care-associated infections program with Oregon Public Health. “If you talk to health care providers on the ground today, they’re asking, ‘What are you doing about C. difficile?’”

Beldavs said Oregon has been fortunate to have had lower hospital-acquired infection rates than other parts of the country, but rates in the state have been on the rise.

The four hospitals in Central Oregon have all seen increases in their rates since 2012. Part of that reflects the switch to a more accurate test that misses fewer cases.

But Dr. Rebecca Sherer, medical director of infection prevention and control for the St. Charles Health System, said rates were on the rise even before the switch to the new test. Surveillance data suggests that same trend may be occurring in the community.

“It’s a challenge for all of us,” Sherer said. “I think it’s the single most important infection-control issue in the nation.”

—Reporter: 541-617-7814, mhawryluk@bendbulletin.com