Inaugural poet discusses ‘The Prince of Los Cocuyos’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, November 9, 2014

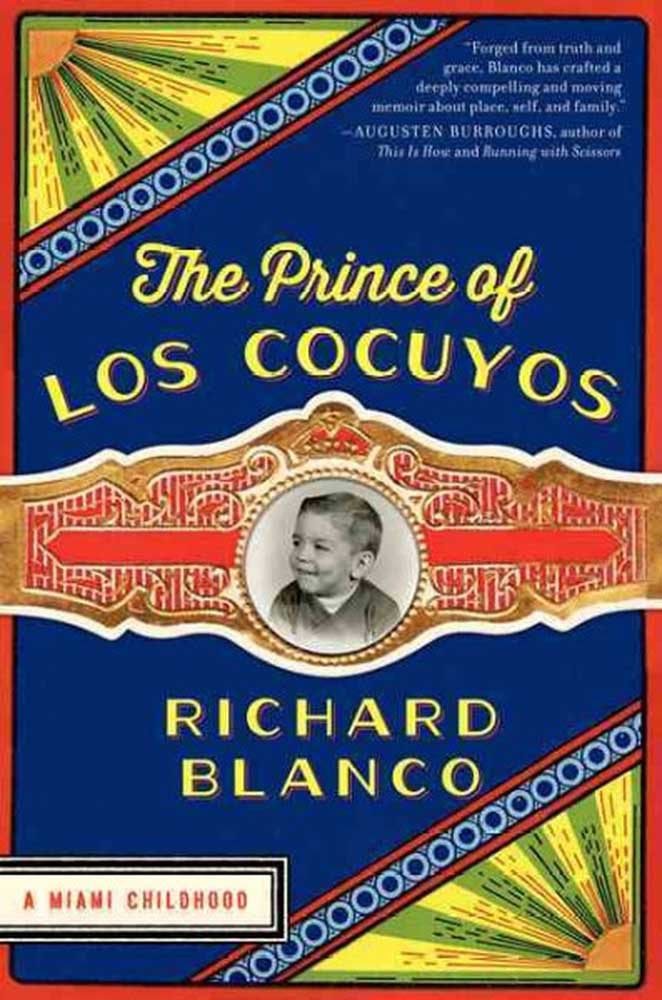

- Submitted photo

“The Prince of Los Cocuyos”

by Richard Blanco (Ecco, 272 pages)

In his new memoir, “Los Cocuyos,” inaugural poet Richard Blanco — who was born in Madrid to Cuban exile parents — revisits his childhood growing up in the Cuban-American community of Westchester, Florida, where he longed to shop at “el Winn Deezee” instead of neighborhood bodegas. He fought with his big brother, endured the tyranny of his tough abuela (who was also a bookie, running a numbers game out of their house) and acted as the perfect Quinces date (even though he wasn’t attracted to girls).

The memoir is deeply grounded in the Cuban-American experience, but Blanco also touches on the universal themes of any childhood: being horrified by your parents, feeling like an outcast and trying to understand love, loss and where you came from.

“That’s part of the goal of most artists, to make that specific work very universal,” says Blanco, who now lives in Bethel, Maine, with his partner. “If you haven’t seen some part of your life in my work, I feel like I failed at something. The irony of art, about writing your story, is you’re being selfish and thinking about your memoir and life, but you have to tap into something universal, some common human denominator. The Cuban exile archetype is about loss, and as humans we all experience loss.”

Campbell McGrath, professor of creative writing at Florida International University, taught Blanco as a student. He says Blanco’s work has long resonated with readers.

“I often teach his first book of poetry, ‘City of a Hundred Fires,’ at FIU in my introduction to creative writing class, and there are two reasons I teach it. One, it’s excellent poetry, and two, the college kids all read it and say, ‘Hey, I know this world.’ They’ve been there especially if they’re Miami kids. They know the kinds of people and neighborhoods and scenery that Richard’s describing. He’s always been documenting his world.”

Writing what he knows earned Blanco the honor of being named the country’s fifth presidential inaugural poet; he was also the first Hispanic and openly gay poet, labels he embraces: “There’s a difference between labels and stereotypes. What else am I going to call myself — a Japanese straight man?”

Blanco has explored his identity and his past through such collections as “Directions to the Beach of the Dead” and “Looking for the Gulf Motel” (his inaugural poem, “One Today,” mentions “hands/as worn as my father’s cutting sugarcane/so my brother and I could have books and shoes”). But with “Los Cocuyos,” he was re-creating his memories in prose, and the unfamiliar form provided a different experience.

“I wondered what my life would look like without line breaks,” he jokes, adding that creative curiosity prompted the project. “Every genre has its limitations, its strengths and weaknesses. There were so many stories I still had in my mind, snippets and characters. I couldn’t write about Easy Cheese in a poem. So I started unpacking everything compressed in my poetry.”

The first chapter, titled “The First Real San Giving Day” — about his efforts to persuade his family to make turkey, not pork, on Thanksgiving — is ground he has covered in his poetry. “Los Cocuyos” travels through other familiar landscapes, though an author’s note warns readers that “these pages are emotionally true, though not necessarily or entirely factual.”

“Some of this book is in really early days, and I have dialogue in there,” Blanco says. “Obviously this is memory stretching at its limits. … As poets, we’re taught to strive for emotional truth. I changed names because I think it’s polite to change the names of people. There’s nothing scandalous here, but I don’t want people to feel exposed.”

Blanco had never worried about his family reading his poetry in English but realized “Los Cocuyos” might eventually be published in Spanish. He admits the idea took him aback, and he asked his brother to read a draft to see whether anything seemed offensive and should be omitted (the answer was no).

What happened instead was that he found his prose had altered some family members in the transition from poetry.

“In poetry, my grandmother is much more vicious and hurtful,” he says. “In the book, she comes across as this likable character. And she was! She was always the life of the party, a fun-loving person. … In the poetry my mother is more of a martyr, always suffering from leaving her whole family in Cuba. But in the book she’s like this control freak, like this warden of the house. I realized that was her psychological response to the loss she had experienced: She wanted to control life. She couldn’t tolerate one more loss in her life.”

Mining that devastating loss and what it means to him has helped Blanco discover his own story, which was forged in Miami.

“One of the real gifts of the inauguration was realizing that my story, my mother’s story, the immigrant story, the gay story, that really they’re an authentic piece of the American story,” he says. “Until the honor of being asked to speak for my country, I wasn’t quite American yet. I wasn’t Peter Brady. America felt like this other place. … But I realized: This is my country. This is where I belong. This is as valid to me as a gay man, as a Cuban man, as it is for anybody else in America. I think it’s going to change my art and make me write about the other ways I can claim America.”