Living centuries apart, sharing parallel worlds

Published 12:00 am Sunday, December 14, 2014

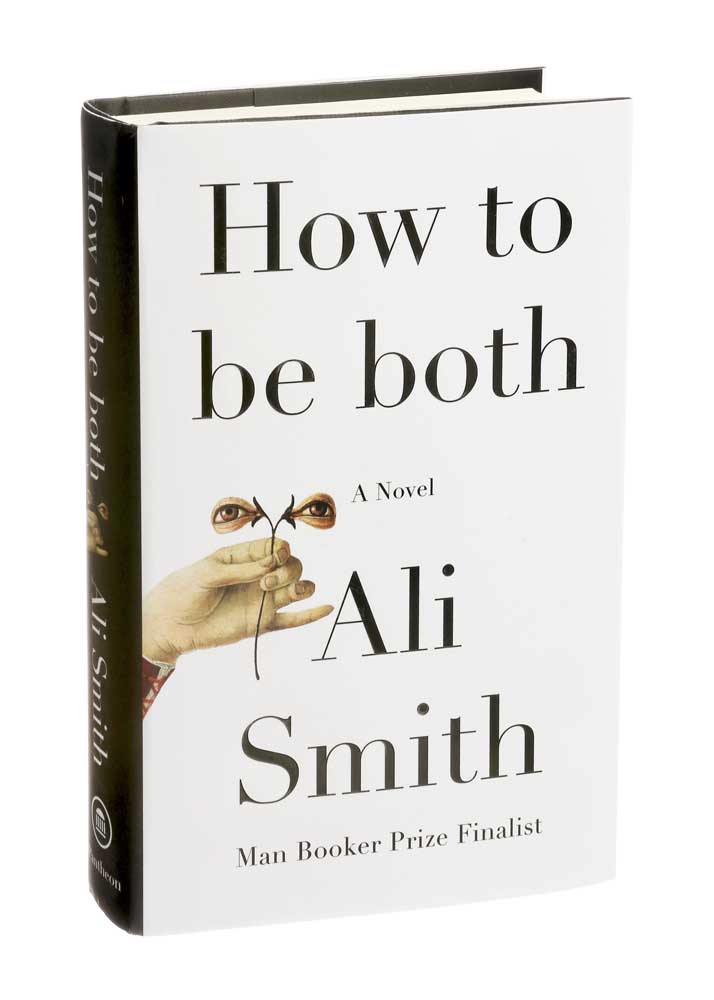

- "How to be Both," by Ali Smith, a Man Booker Prize finalist published in the United States by Pantheon, in New York, Dec. 7, 2014. In this complex novel exploring dualities in art, life and gender identity, a contemporary teenaged girl and Renaissance painter are linked across centuries. (Patricia Wall/The New York Times)

“How to Be Both” by Ali Smith (Pantheon Books, 372 pages)

As an introduction to the conundrums and complexities of Ali Smith’s bicameral novel “How to Be Both,” consider this conversation between a hairsplitting teenage girl named George and her more loosely cerebral mother. The mother is dead, and the conversation is taking place in George’s memory. But let’s not get too complicated — yet.

In George’s memory, it is “last May in Italy.” Mother, daughter and George’s brother, Henry, have traveled south from their home in Cambridge, England, to see an early Renaissance fresco by an artist whose seemingly unrelated story is the other half of “How to Be Both.”

Mother and daughter are talking about the restoration of frescoes. As Smith writes it:

“But which came first? her mother says. The chicken or the egg? The picture underneath or the picture on the surface?

The picture below came first, George says. Because it was done first.

But the first thing we see, her mother said, and most times the only thing we see, is the one on the surface. So does that mean it comes first after all? And does that mean the other picture, if we don’t know about it, may as well not exist?”

This same question, and many others, will arise in both halves of the novel, though in drastically different circumstances. This is not a book to be read passively, or even to be read once, especially since it takes a while to figure out how its two parts are connected. To amp up her gamesmanship, Smith has had “How to Be Both” published in two editions, so that the sequence of its halves varies from copy to copy: Some have George’s story first, some the Renaissance artist’s.

“How to Be Both,” a finalist for this year’s Man Booker Prize, is more accessible, yet more ordinary, if George’s story comes first. It’s knottier and more challenging if you begin reading about Francescho del Cossa, a Renaissance painter of the 1460s and ’70s (whose first name is more commonly spelled Francesco — but here, as always, Smith has her reasons). And it’s knottier and more challenging if you wonder why this artist keeps conjuring a 21st-century girl with some kind of magic tablet and a portrait of a blonde he thinks must be “St. Monica Victims” on her wall.

Actually, the Renaissance man is seeing Monica Vitti on an Antonioni movie poster, because George’s mother was a great fan of 1960s cinema. (Too great a fan: George hates being named for the title character in the 1966 “Georgy Girl.”) In addition to sharing grief for a lost mother with George, Francescho happens to be dead, too, which is not surprising for someone born in 1430.

Smith is quite distinct about the kinds of questions she wants contemplated and the kinds she wants ignored. For instance, we’re used to having present-day characters conjure the past. But Smith might have elaborated on how an artist dead for centuries can see a computing device.

Never judge a book by its structure. “How to Be Both” has a lot more allure than its overall rigor suggests, thanks to the obvious pleasure that Smith takes in creating her peculiar parallels and exploring the questions they raise. Strange as it may seem, the British teenager and the painter who must curry favor with wealthy fools if he wants work have quite a bit in common. For one thing, both are sexually drawn to women. In Smith’s imagination, Francescho is a woman, but she must conceal that fact if she wants to be taken seriously as an artist.

And both are fascinated by sex, but primarily as spectators. George watches the same porn film (possibly set in a yurt) over and over on her tablet, as if she were obligated to do so. Both characters are presented by Smith as outsiders who do only what they must to tolerate the behavior of others. About the therapist that George is forced to see after her mother’s death, the book says: “Mrs. Rock sits next to her table in front of George like a mainland off an island for which the last ferryboat of the day is already long gone.”

The inspiration for this mélange of a book, sometimes so ingenious and sometimes just willfully odd, is Francescho del Cossa’s fresco at the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, Italy. Take one look at pictures of this work and you will want to race right off to see it, which is apparently what Smith did.