Harvard: Low-glycemic foods can help control weight

Published 12:00 am Thursday, December 18, 2014

- Harvard: Low-glycemic foods can help control weight

A Harvard University health newsletter this month touted the benefits of eating foods with a low gylcemic index in order to control weight by staying fuller longer.

Glycemic index — generally measured on a 1 to 100 scale, although some foods are higher — represents the amount of time it takes for a food to digest and for the sugars to be released into the bloodstream. High-glycemic foods release glucose quickly into the blood, creating an insulin boost that causes the blood sugar to plummet within a couple hours. Low-glycemic foods are preferable because the glucose in them flows slowly into the bloodstream, releasing insulin gradually and keeping a person fuller longer.

Trending

A handful of dietitians interviewed on the subject, however, said the glycemic index isn’t something they routinely talk about with their clients, even those who have diabetes. The reason? It’s too complicated. Throwing more numbers at people who already are counting calories or other components of their diet — especially if they’re managing a health condition — simply gets to be too much.

“It’s just one more thing to balance,” said Susan Yesavage, a diabetes educator at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore. “So if you just focus on fresh foods, whole foods, it makes the selections … healthier, and also easier to make.”

The underlying message behind the glycemic index is an important one, however: Eat whole, unprocessed, plant-based foods. They tend to be high in fiber, a type of carbohydrate that can’t be broken down and instead passes through the body, helping regulate blood sugar along the way. Low-glycemic foods, such as whole grains, beans, fruits and vegetables, tend to be high in fiber.

“Really, at the end of the day, it’s a high-fiber diet,” said Lori Zanini, a registered dietitian in Los Angeles and spokeswoman for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Harvard’s newsletter provides an important reminder of the importance of choosing foods high in fiber and low in refined sugars when it comes to energy regulation and weight loss.

For those struggling with their weight, eating high-glycemic foods can fuel a cyclical eating pattern that prevents them from shedding pounds. That’s because they might choose high-glycemic foods for breakfast — say, a bowl of Cornflakes and some cranberry juice cocktail — and then feel tired, shaky and woozy when their blood sugars plummet just a few hours later. At that point, there’s a tendency to want to recover quickly by grabbing a high-glycemic snack that will replenish blood sugar within minutes.

Trending

“You kind of crave something that’s going to satisfy you quickly and raise your blood glucose, and so then it’s a vicious cycle,” said Lori Brizee, a registered dietitian and owner of Central Oregon Nutrition Consultants.

For people with diabetes or severe hypoglycemia — low blood sugar — that quick fix is essential to avoid passing out, but it’s important that people don’t overcorrect and bring their blood sugar too high, said Yesavage, of Johns Hopkins.

“What I do stress with any person with diabetes is that when you’re fixing low blood sugar, this is not for enjoyment,” she said. “You need to get the blood sugar up rapidly into a normal range but you also need to keep it there. So we’re not saying reach for sugar as a normal staple.”

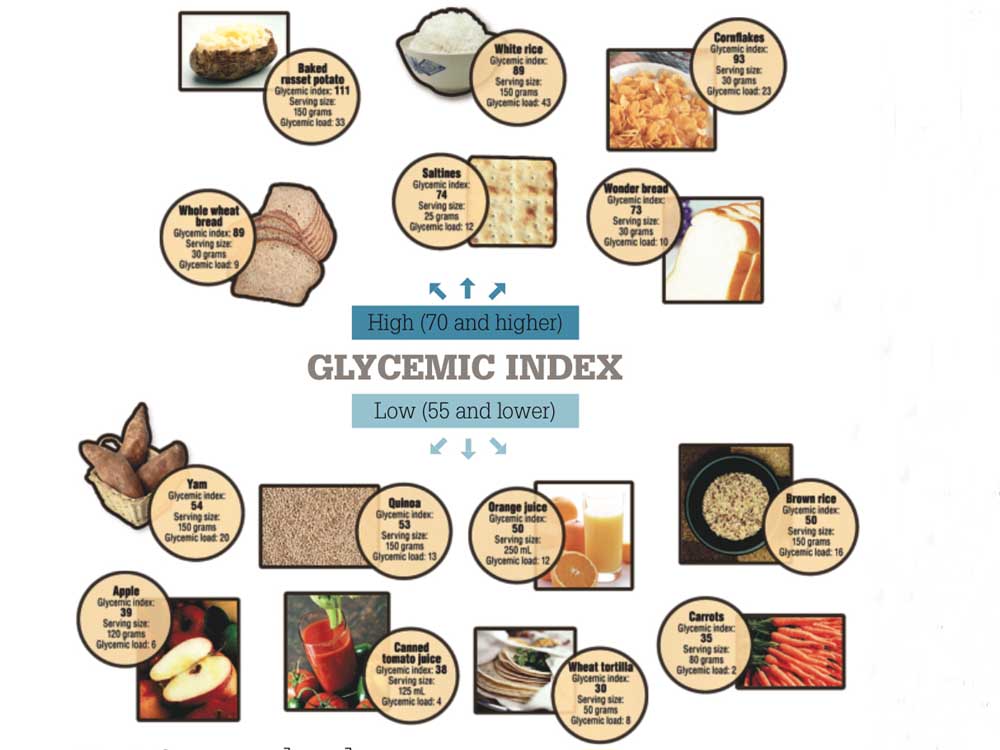

The American Diabetes Association defines low-glycemic foods as those with a glycemic index of 55 or lower, such as chickpeas (10), peanuts (7) or grapefruit (25).

Medium-glycemic indexes are those between 56 and 69, and high-glycemic foods are those 70 and up, such as a baked russet potato (111), white rice (89) or Gatorade (78).

Glycemic load is a measure of a food’s glycemic index combined with its carbohydrate content, which can also affect blood glucose.

A research team at the Harvard-affiliated Boston Children’s Hospital studied the effectiveness of using a low-glycemic diet to keep extra pounds off. In 2012, they compared the low-glycemic diet to low-fat and low-carb diets and found that although the low-carb diet resulted in more calories burned, the low-glycemic diet burned more calories than the low-fat diet and didn’t have the negative side effects of the other two diets, including lower levels of good cholesterol and increased levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

In 2013, Harvard researchers performed imaging tests on participants’ brains four hours after they had consumed high- and low-glycemic meals. Those who had eaten the high-glycemic meals showed higher blood sugar levels, increased hunger and heightened senses of cravings and reward in regions of the brain that are stimulated before a meal.

The Harvard newsletter, called Harvard Women’s Health Watch, also said that research has linked low-glycemic diets with decreased risk of diabetes, heart disease and certain cancers.

But a study released this month in the Journal of the American Medical Association found eating low-glycemic foods instead of high-glycemic foods did not improve cardiovascular risk factors, such as HDL — nicknamed “good” cholesterol — triglycerides or blood pressure, or insulin resistance among 163 overweight, non-diabetic adults. The researchers did find, however, that low-glycemic diets increased blood sugar levels by 2.5 milligrams per deciliter while fasting.

In the study, the researchers stipulated they weren’t studying glycemic index’s effect on weight loss, and noted that past research has found both positive impacts in this area as well as no impacts.

If you’re considering a low-glycemic diet, Zanini cautions not to forget about portion size.

The way foods are prepared can impact their glycemic index, too, she said. For example, a semi-green banana will have a lower glycemic index than one that’s become ripe and almost brown. Likewise, pasta that’s cooked firmer will have a lower glycemic index than pasta that’s cooked until it’s mushy. And the more processed a food is, the higher glycemic index it will have, Zanini said.

“That’s just kind of a common sense thing, the more something is processed, then when we eat it, it breaks down faster in our bodies,” she said.

— Reporter: 541-383-0304,

tbannow@bendbulletin.com