Album reviews

Published 12:00 am Friday, January 16, 2015

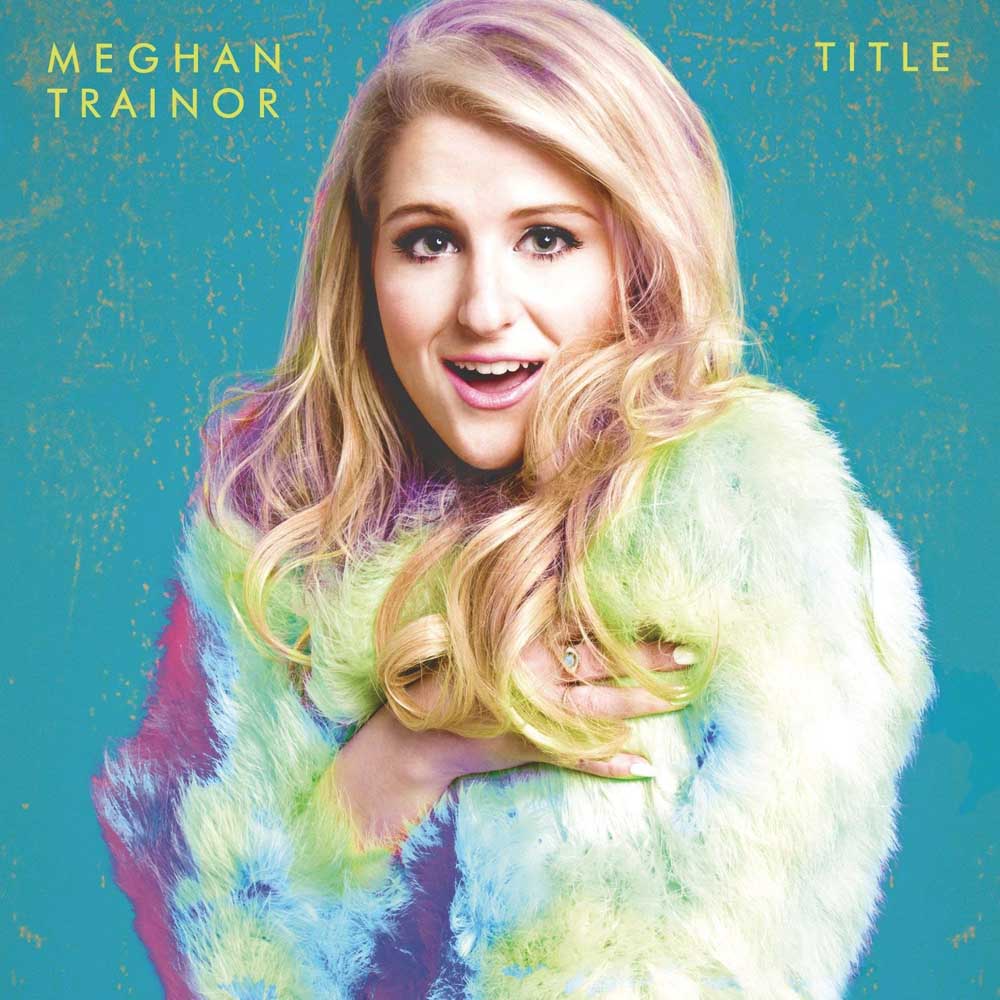

- Meghan Trainor, "Title"

Justin Townes Earle

“ABSENT FATHERS”

Vagrant Records

Sorrow, betrayal, breaking up and lingering resentment are inexhaustible sources for alt-country songwriter Justin Townes Earle. “These old stories always end up the same/ The pain is the price you pay,” he sings in “Call Ya Momma,” one of the many breakup songs on his sixth studio album, “Absent Fathers.” It follows closely on his fifth one, “Single Mothers,” which Earle released in September.

Both were recorded at the same sessions, but Earle ended up grouping the more confident-sounding songs — musically, at least — on “Single Mothers.” On “Absent Fathers,” he’s more openly forlorn. The two releases play through like a double album. They start strong, ease back, pick up again and end with a pensive farewell: the fingerpicked acoustic ballad “Looking for a Place to Land.”

The music isn’t pumped up with arena-rock flourishes or computer tricks, and it doesn’t hide bruises and aches. It draws proudly on Southern soul, particularly in “When the One You Love Loses Faith in You.” The albums aren’t a narrative, but Earle plays a recurring character: A guy who’s no prize himself but who’s wounded anew with each separation. Both albums, particularly “Absent Fathers,” are a finely tuned wallow in male heartache.

— Jon Pareles,

New York Times

Justin Kauflin

“DEDICATION”

Qwest Records/JazzVillage

“Dedication,” the new album by Justin Kauflin, broadcasts on at least two frequencies. It’s a declaration of purpose by a diligent young post-bop pianist eager to make his mark in a crowded field. It’s also the fulfillment of a promise, given Kauflin’s role in “Keep On Keepin’ On,” a moving documentary film about his friendship with the august jazz trumpeter Clark Terry.

The film, likely to be in the running at this year’s Academy Awards, depicts Kauflin as a respectful, humble and unassuming young man, self-doubting at times but as unfazed by the high demands of his art form as he is by his blindness.

What the film also reveals are some uncommon advantages bestowed on Kauflin, first by Terry, a generous mentor, and then by Terry’s former protégé Quincy Jones, who took the young pianist under his own wing: He signed Kauflin to his management company and took him on tour before producing this album.

So one measure of Kauflin’s achievement with “Dedication” is that the album — a dozen original tunes, played in quartet, trio and solo formats — quickly makes you forget about its meta-narrative.

As a pianist, Kauflin, 28, favors a clarity of touch and ideas, rarely spinning into an orbit he can’t control. His writing is also balanced, tempering post-bop intricacies with the assurances of the gospel church. “For Clark,” a pastoral ballad that had its moment in the film, arrives without fanfare, one of several tributes, including two in polyrhythmic triplet meter: “The Professor,” for pianist Mulgrew Miller, and “B Dub,” for drummer Billy Williams.

The trio, with Williams and bassist Christopher Smith, moves with an unstudied grace, while the quartet, featuring Matthew Stevens on guitar, feels like a vehicle for the compositions. Kauflin seems inclined to use both options well.

— Nate Chinen,

New York Times

Swamp Dogg

“THE WHITE MAN MADE ME DO IT”

Alive Naturalsound Records

It was 1970 when singer, songwriter, and producer Jerry Williams unveiled his Swamp Dogg persona and promised “Total Destruction to Your Mind” on the title song of his cult-classic debut. Now here it is, 45 years later, and not only is the outrageously entertaining agitator and jester still at it, he has one of the first standout albums of 2015.

“The White Man Made Me Do It” follows the time-honored Swamp Dogg formula: Whether anguishing over a “Lying Lying Lying Woman” or delivering righteous messages on race and politics, he frames the songs in irresistibly tight, horn-stoked Southern soul, with occasional traces of gospel and country.

With “Where Is Sly?,” Swamp Dogg pays tribute to Sly Stone, a visionary artist who helped inspire the young Jerry Williams to be himself. “Is he off somewhere still getting high?,” Swamp Dogg wonders. Sly may have lost his way and squandered his talents, but his disciple certainly hasn’t.

— Nick Cristiano,

The Philadelphia Inquirer

Meghan Trainor

“Title”

Epic Records

Meghan Trainor breezes past troubles on “Title,” the debut album that follows her 2014 smash “All About That Bass,” which spent eight weeks at No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100. Last month it also earned Grammy nominations for record and song of the year.

A cheeky doo-wop throwback that starts out with the singer admitting she “ain’t no size 2,” “All About That Bass” wooed fans by the millions with its old-fashioned sound — a welcome standout on dance-dominated Top 40 radio — and its ostensibly self-affirming message.

“Every inch of you is perfect from the bottom to the top,” Trainor sings, just after she calls out fashion magazines for presenting unrealistic images of female beauty.

Yet “All About That Bass” attracted criticism too for its blithe dismissal of “skinny bitches,” to use Trainor’s phrase, and the regressive sexual politics of a song that champions a larger body size at least in part because “boys like a little more booty to hold at night.”

The song also raised suspicions, in the year of Iggy Azalea, about the racial appropriation at work in Trainor’s singing style.

But if any of that controversy alarmed the 21-year-old singer, she certainly doesn’t show it on “Title,” which basically offers a dozen variations on “All About That Bass” (including “Lips Are Movin’,” another Top 5 hit). Each song is as cheerful and crafty — and as vexing — as Trainor’s breakout hit.

Over a bouncy refashioning of the groove from Dion’s “Runaround Sue,” she pledges to be “the perfect wife” in “Dear Future Husband,” as long as her man does right by her.

At first, Trainor seems to be sketching a union of equals. “You got that 9-to-5 / But, baby, so do I,” she sings, “So don’t be thinking I’ll be home and baking apple pies.” Soon, though, she’s shoring up more conventional ideas about a woman’s role in a marriage: “You gotta know how to treat a lady / Even when I’m acting crazy.”

There’s room, of course, in a pop song for these contradictions. In fact, there’s room in these specific pop songs, so cleverly designed by the singer and her principal collaborator, producer Kevin Kaddish, whom Trainor met following her brief stint as a professional songwriter in Nashville. (She only recorded “All About That Bass,” the story goes, after they failed to sell the tune to an established artist.)

As a performer, though, Trainor never owns them.

Unlike, say, Bruno Mars — an avowed idol of hers who similarly mixes modes and attitudes — she doesn’t give you the sense that she’s thought through the opposing themes in her music: the individual versus society, modernity versus tradition, dependence versus independence. It all feels as unexamined as her use of certain vocal patterns typically associated with black singers.

Which would be fine, perhaps, if so much of this album didn’t insist that each of us has a responsibility to live his or her personal truth.

“Everybody’s born to be different / That’s the one thing that makes us the same,” Trainor sings over a Santo & Johnny-style slow-dance shuffle in “Close Your Eyes.” “So don’t you let their words try to change you / Don’t let them make you into something you ain’t.”

One wishes “Title” gave us a better sense of the person resisting that pressure.

— Michael Wood,

Los Angeles Times