Use of IUDs increasing

Published 12:00 am Thursday, January 22, 2015

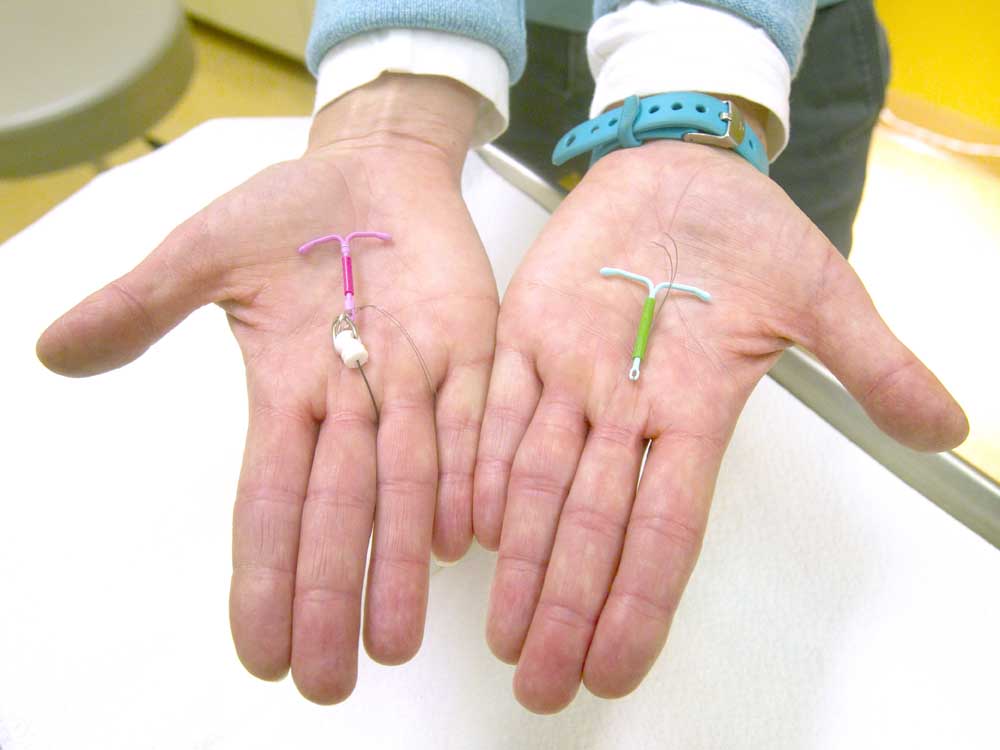

- Andy Tullis / The BulletinDr. Susan Gorman shows the Skyla IUD, left, and the Mirena IUD, at High Lakes Womans Center in Redmond.

When Dr. Barbara Newman attended medical school back in the late 1970s, her teachers trained her never to use a form of contraception called the intrauterine device, or IUD, on young women who had never had children.

That was on the heels of the historic failure of a poorly designed IUD called the Dalkon Shield, which was the subject of roughly 200,000 lawsuits from women who reported severe infections and uterine perforations. An IUD is a T-shaped plastic device inserted into the uterus that prevents pregnancy by releasing either copper or hormones.

Trending

The Shield’s impact lingered for decades in the minds of physicians and the public alike — even as improved products hit the market — stunting the use of what countless doctors now say is the most effective reversible form of birth control out there.

Even for Newman, medical director for women’s services at St. Charles Health System, who now readily recommends IUDs to patients in their teens and older, it wasn’t an easy shift to make. But as data accumulated showing newer models didn’t carry the same risks as the old ones, she couldn’t ignore it.

“It was a difficult thing to do,” she said. “I came out with all this training, ‘Don’t do it, don’t do it,’ so yeah, it definitely took a shift to make that happen.”

New data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention illustrate a sea change in the past decade toward more and more women choosing IUDs as their contraceptive method. They’re now the third most popular form of birth control. Nearly 12 percent of women who used contraception in the U.S. between 2011 and 2013 chose long-acting, reversible contraceptives, a category comprised mostly of IUDs, but which also includes a form of contraceptive called implants, tiny, hormone-releasing rods inserted into the upper arm.

In 2002, only 2.4 percent of women used IUDs, according to an analysis by the Guttmacher Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to reproductive health issues.

Pills are still the most popular form of contraceptive, at 26 percent, according to the institute. Condoms are the second most popular, at 15 percent.

Trending

At first blush, it might seem as though the device’s newfound affordability under the Affordable Care Act is behind its increased use. The Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines require insurers to cover all forms of contraception without copays beginning Aug. 1, 2013. Now, a method that used to run roughly $1,000 for the device and insertion procedure (also included in the new law) is free for most women with insurance.

“It really is a combination of good publicity, good research, the Affordable Care Act — I just think it’s an interesting perfect storm at this point,” said Dr. Alison Lynch-Miller, a Bend gynecologist, “and I’m thrilled, really, to see IUD use increasing.”

Lingering concerns

But Megan Kavanaugh, senior research associate with the Guttmacher Institute, said the CDC data was only collected until spring 2013, which probably didn’t allow much time for the ACA provision to effect IUD usage rates at that point. More recent research, however, has shown the provision has increased IUD use even more, she said.

Provider awareness is the biggest factor Kavanaugh attributes to the nearly 10 percent increase in IUD use over a decade. Well-respected medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, are now recommending them for young women. That wasn’t the case with IUDs in the past, she said.

“They weren’t the first ones that came up, with the provider saying, ‘These would be great methods for you,’” Kavanaugh said. “I think that’s what’s gradually changing. We’re seeing that in the clinical community, and I think that’s trickled down into the patients themselves.”

That doesn’t mean everyone’s convinced. A 2012 CDC survey found that 30 percent of providers perceived IUDs to be unsafe for women who had never given birth.

The fears about IUDs linger among physicians and patients alike, Lynch-Miller said.

“But it’s nothing like when I first started practice in ’94,” she said. “You could hardly talk to people about having IUDs.”

All IUDs have strings that protrude from the cervix so they can be removed. The problem with older IUDs was their multifilament strings, which promoted pelvic infection, Lynch-Miller said. Today’s monofilament models are less likely to do so, she said.

That said, today’s IUDs still carry risks. In roughly one out of 1,000 cases, they’ve been shown to perforate the uterus, a side effect that sometimes requires surgery.

Perforation most commonly occurs while the IUD is being inserted, and the more experience a physician has, the less likely perforation will happen, said Dr. Lauren O’Sullivan, a Bend gynecologist and surgeon who works in the same clinic as Lynch-Miller.

Patients should “absolutely” feel comfortable asking their physician how many IUDs he or she has inserted, as experience is critical, Newman said.

More commonly, IUDs can be pushed out of the uterus into the vagina. This doesn’t typically cause injuries, but it does take away any protection against pregnancy. That happens in roughly 1 out of 100 cases.

Copper IUDs also are known to increase menstrual bleeding, while the hormonal varieties decrease bleeding.

A handful of Central Oregon gynecologists interviewed said those side effects are rare and are outweighed by the benefit of a highly effective form of birth control that women don’t have to think about after it’s inserted.

Most research has found that less than 1 percent of women who use IUDs become pregnant. By comparison, roughly 9 percent of women who use pills become pregnant.

Among women who use the pills “perfectly,” meaning both consistently and correctly, the failure rate of birth control pills is 0.3 percent, according to a 2011 study in the journal Contraception. But “typical” use results in 9 percent of women becoming pregnant, the study found.

“Women have to be assiduously aware of what’s going on with their pills and not to miss any,” Newman said. “That is a big drawback.”

Some docs favor Mirena

There are three types of IUDs on the market today: Mirena, Skyla and ParaGard.

The former two work by releasing a low dose of levonorgestrel, a progestin hormone, into the uterus, which prevents pregnancy by inhibiting sperm movement, thinning the lining of the uterus and thickening cervical mucus.

Mirena, which protects against pregnancy for five years, was federally approved for use in 2000.

Skyla, effective for three years, was approved in early 2013. It’s marketed for younger women who haven’t had children because it’s smaller and releases a lower dose of levonorgestrel.

ParaGard’s frame is wrapped in copper that continuously releases into the uterus, producing a reaction that’s toxic to sperm. It’s been on the market for about 30 years and is effective for up to a decade after it’s inserted.

Dr. Susan Gorman, a gynecologist with the High Lakes Women’s Center in Redmond, said Mirena is the ideal IUD because it reduces or eliminates periods, which is especially helpful for women who have heavy periods or spotting between cycles.

However, some patients prefer to not have any hormones put into their bodies. For them, ParaGard is the preferred option, she said.

O’Sullivan said she uses Mirena 100 percent of the time because it reduces bleeding during periods, while ParaGard increases bleeding.

“I feel, from a woman’s standpoint, that it’s doing a disservice to increase their bleeding with their period,” she said. “There is no medical reason why they should have to have a heavier period.”

Skyla is designed for women with shorter uteruses, so whether it’s the better choice isn’t typically known until the day the IUD is placed, O’Sullivan said.

The Guttmacher Institute credits increased IUD use with fewer unintended pregnancies in the U.S., using data showing 13 percent fewer abortions between 2008 and 2011 and an even steeper decline in births.

Women today are typically becoming sexually active around age 18 and delaying birth until 25, Kavanaugh said.

“That’s a long time frame within someone’s life in which they need to prevent pregnancy,” she said, “and that’s also the time frame in their life in which they’re at highest risk for unintended pregnancy.”

— Reporter: 541-383-0304, tbannow@bendbulletin.com