No Headline

Published 12:00 am Friday, January 30, 2015

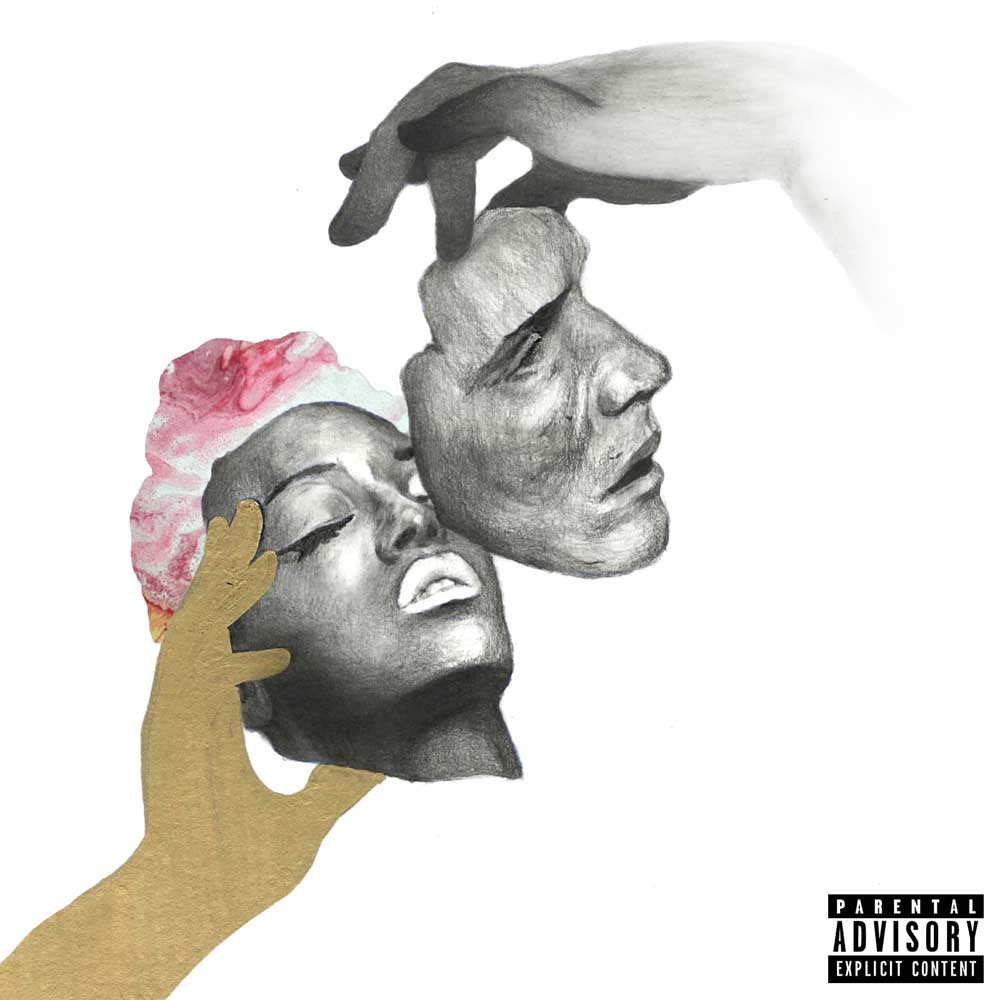

- Dawn Richard, "Blackheart"

Björk

“VULNICURA”

One Little Indian Records

In the opening measures of Björk’s new album, “Vulnicura,” the Icelandic artist offers a direct statement of purpose, one involving personal upheaval she describes as “a juxtapositioning fate.” Mentioning “moments of clarity as so rare, I better document this,” Björk directs her gaze in that first song, “Stonemilker,” on the dissolution of a relationship.

As she does so, what can be described only as Björkian strings and beats swirl around her. These drifting arrangements soar through tracks like birds spinning circles in prairie skies, even as the experimental pop singer, 49, lyrically crawls through the brush below in utter confusion. At times devastated, others baffled, still others strong and determined, the artist on “Vulnicura” offers nine songs, six of which move in chronological order through that juxtapositional end and beyond.

The artist’s most personal record in a career full of vocal and emotional drama, “Vulnicura” is a self-described “complete heartbreak album,” its title Björk’s own invented word. What it defines, though, is as lyrically raw and shockingly direct as Marvin Gaye’s “Here, My Dear” or Beck’s “Sea Change,” and seems to document the end of her relationship with the visual artist Matthew Barney.

Referring to herself in a Facebook post as being “kinda surprised how thoroughly I had documented this in pretty much accurate emotional chronology,” the artist considered her creations to be “like 3 songs before a break up and three after.” On early listens — the record arrived with little notice on Tuesday night — it’s an exquisite, inspired and typically angular listen, filled with much texture and impatient roaming, with musical and vocal tones built into spatial structures that fearlessly trace the lyrical ordeals.

Though Björk, who has a daughter with Barney, never mentions her ex by name, she delivers lines about family — mothers, fathers and daughters in “Family” — that make it painfully apparent this is her take on a real-life situation. (Barney and Björk reportedly ended their decade-long relationship in 2013.)

Bjork has seldom minced lyrics. Her previous album, “Biophilia,” was thematically linked through lyrics about nature and the environment; her mostly a cappella 2004 album “Medúlla,” recorded while she was pregnant, was overtly political. Rising in the 1990s after gaining popularity as the singer of Sugarcubes, her solo career has drawn on experimental electronic dance music and contemporary classical music, tracing and mixing styles and collaborating with musicians eager to work with such a voice.

Nuanced and miraculously expressive, her vocal cords growl and scowl, soar like clarinets and wail like violins. Hinting at voices as varied as Meredith Monk, Kate Bush, Maria Callas and the guy who sang “Surfin’ Bird,” it delivers singular vibrations.

She has thrived within musical partnerships, even as her work has traveled far afield of so-called popular music. Over the decades and seven earlier studio albums (excluding her self-titled 1977 debut, released when she was a young Icelandic pop star), she has teamed with innovative creators including Tricky, Matmos, Matthew Herbert, Mouse on Mars, Zeena Parkins and Mark Bell. For “Biophilia,” Björk worked solely with the British dubstep producers 16bit.

“Vulnicura” sees her collaborating with a new pair: the English ambient producer who makes music as the Haxan Cloak and the Venezuelan producer Arca, whose tracks with Kanye West and FKA Twigs have driven his rise. As usual, Björk arranges much of “Vulnicura” herself, with modernist string bursts, drifting, expansive patterns and punctuated squawks.

Those words are penned with a diary-esque honesty. “Stonemilker,” for example, is accompanied in the liner notes with the descriptive, “nine months before.” The next song “Lionsong” is described as occurring “five months before.” The brief “History of Touches” (“three months before”) hints at fading passion and a final bout of passion.

During the epic 10-minute centerpiece, “Black Lake” (“two months after”) after describing “my soul torn apart, my spirit is broken,” Björk goes for the jugular: “You have nothing to give / Your heart is hollow / I’m drowned in sorrows / No hope in sight of ever recover / Eternal pain and horrors.”

On “Notget,” Björk hits hard: “Without love I feel the abyss / Understand your fear of death.”

After those first six songs, the singer abandons time-stamping and moves through three closing pieces without markers. Suggesting that the end is evolving into a beginning, these works arrive like dawn after a thunderstruck night.

Collaborating with New York singer Antony, she sings of “fine-tuning my soul” in “Atom Dance,” of letting “this ugly wound breathe” and “peeling off dead layers of loveless love.”

During a beat-heavy highlight, “Mouth Mantra,” the artist circles around and through Arca’s rhythms with sheets of sampled, manipulated voice, while lyrically addressing writer’s block.

“Vulnicura” is a serious, heavy journey through a rough ordeal, a work certainly too deep to fully absorb so quickly after its release. Like many of her recent records, it’s not toe-tapping beat-based music. But fans like myself will find much to love as we explore its many peaks and valleys.

Whether the unnamed ex feels the same is another story.

— Randall Roberts,

Los Angeles Times

Jamie Cullum

“INTERLUDE”

Island Records/Blue Note Records

There’s an implicit warning in the title of Jamie Cullum’s standards album, “Interlude.” In case it needs spelling out, the title track — a Dizzy Gillespie tune recorded by Sarah Vaughan, before it became the bebop instrumental “Night in Tunisia” — opens the album with lyrics about an ardent but fleeting love. “The magic was unsurpassed,” Cullum sings, drawing out his vowels. “Too good to last.” Right: Don’t get too attached.

Cullum, 35, has spent the past decade or so as the rare singer-songwriter to find big success at the crossroads of jazz and pop, equipped with his raffish charm, his limber voice and his uncorked energies onstage. “Interlude” has been marketed as his return to jazz, which is true insofar as its repertory skews heavily toward the American songbook, with spruce acoustic arrangements.

You could know just that much about the album and dismiss it out of hand, but Cullum has dodged most of the usual pitfalls, proceeding with respect (but not too much) and a spirit of license (within clear bounds). Crooning Rat Packish ballads like “Make Someone Happy” and “Come Rain or Come Shine,” he can still suggest a junior Harry Connick Jr., accentuating emotional connection over vocal technique.

What makes “Interlude” a far more interesting proposition are its less obvious choices, starting with the personnel. Rather than recording the album with his usual sidemen, Cullum enlisted Benedict Lamdin, a producer also known as Nostalgia 77, to put together a band. Many of the tracks were recorded in a single room; some, like a euphoric strut through Ray Charles’s “Don’t You Know,” were done in a single take.

It’s probably no accident that Cullum, a British musician weaned on rock and hip-hop, envisions an American songbook that includes “Don’t You Know.” Along similar lines, he’s duly sensitive on Randy Newman’s “Losing You” and smartly outfits a Sufjan Stevens song, “The Seer’s Tower,” with an arrangement inspired by Nina Simone.

Also coming from the Simone playbook is “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” — performed as a duet with Gregory Porter, who sounds so much more hale and soulful that the track’s inclusion almost counts as self-sabotage.

Cullum fares better with Laura Mvula on “Good Morning Heartache”: The two singers move with careful grace, like new partners circling a dance floor, neither making any promises about sticking around.

— Nate Chinen,

New York Times

Dawn Richard

“BLACKHEART”

Our Dawn Records

Best known as an original member of Danity Kane, R&B singer Dawn Richard left the group last year (again) after a public kerfuffle revealed deep divisions among the crew. No disrespect to the others, but Richard is thriving without them. Over the last few years she’s issued a series of works that hinted at a wildly visionary approach to soul sonics, and she’s gone even further on “Blackheart.”

A collaboration with the Los Angeles producer Noisecastle III, Richards’ second studio album is thick with synth-based polyrhythms and layers of Richard’s often breathtaking voice. When delivered straight, it’s solid and pitch perfect. More often, though, she and Noisecastle run her words through strange filters, electronically manipulating it to move from male bass to female soprano and beyond. She merges her words with Vocoders like she’s rolling onto Kraftwerk’s “Autobahn,” hums with Giorgio Moroder-like synth throbs. The result is magnetic future funk, rife with Roland 909 tones, British drum and bass accents and much left-field surprise.

— Randall Roberts,

Los Angeles Times