More album reviews

Published 12:00 am Friday, February 6, 2015

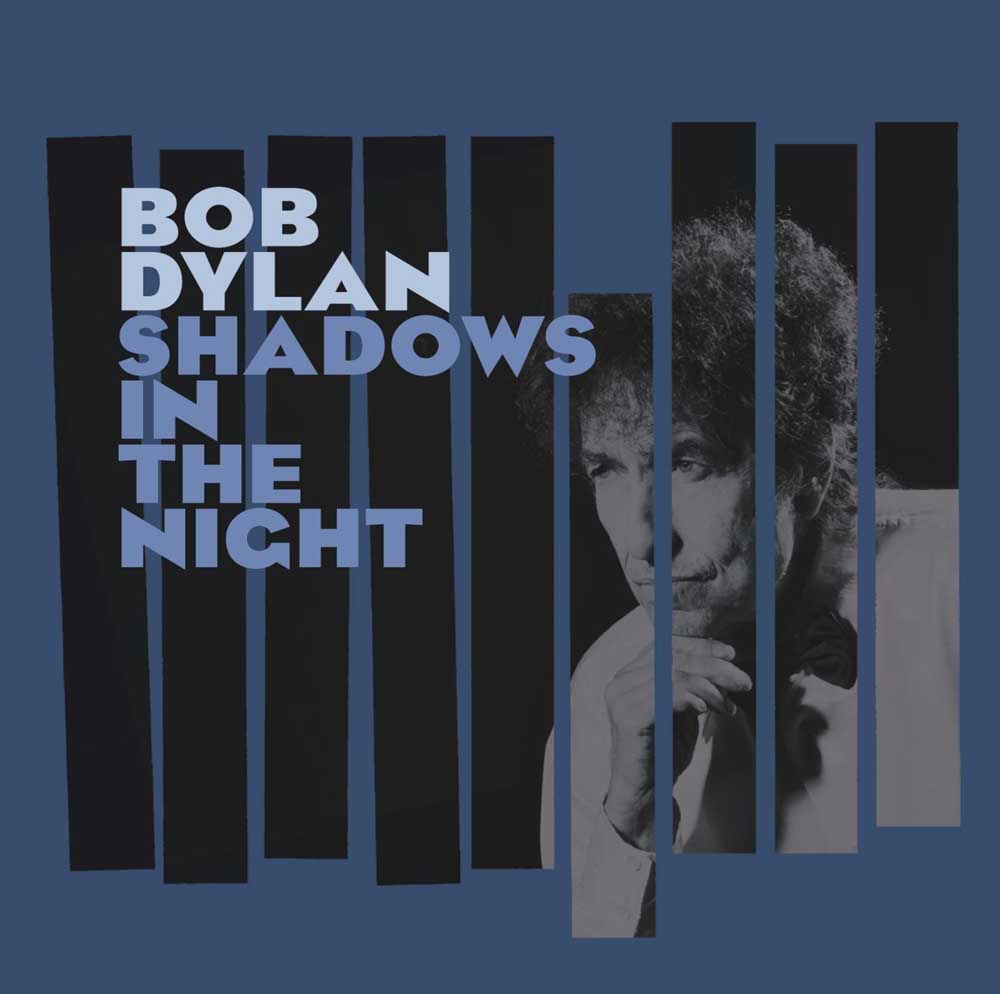

- Bob Dylan, "Shadows in the Night"

Bob Dylan

“SHADOWS IN THE NIGHT”

Trending

Columbia Records

It’s not a put-on. Bob Dylan’s “Shadows in the Night,” an album of 10 songs that were all recorded by Frank Sinatra, is a tribute from one venerated American musician to another, a reconsideration of a school of songwriting, a feat of technical nostalgia and a reckoning with love and death.

Dylan devotes the album to a particular subset of the Sinatra legacy. It’s not Sinatra the airborne swinger or Sinatra the voice of confidence. It’s the Sinatra who made thematic albums about separation and heartache — albums like “Where Are You?” in 1957, which included four of the songs Dylan revives, and “No One Cares” (1959) and “All Alone” (1962), which each supply one. They are ballads, mostly Tin Pan Alley standards, sophisticated enough to be utterly succinct. They never move faster than midtempo and they often luxuriate in melancholy; they testify, above all, to loneliness.

“Shadows in the Night” (Columbia) offers bait for trivia seekers. Sinatra was born in 1915, 100 years ago. The opening track, “I’m a Fool to Want You,” is one of very few songs with a Sinatra songwriting credit. The front cover emulates the vertical-bar design of the jazz trumpeter Freddie Hubbard’s album “Hub-Tones,” which was released — like Dylan’s debut album — in 1962. The photo on the back poses Dylan and a masked woman in formal wear at a nightclub table, alluding, perhaps, to the 1966 Black and White Ball, a masked ball that gathered a glittering assortment of 1960s celebrities, including Sinatra and his new wife, Mia Farrow. In the photo, Dylan holds a Sun Records single, a touch of rock; its title is too grainy to decipher.

But there’s no posing in the music. Dylan went to a studio where Sinatra often recorded, Capitol Records’ Studio B, and he sang the songs with his five-man touring band. They recorded live and listening to one another in the room without headphones; turn the album up too loud and you can hear amplifiers humming as songs begin and end.

“There was no tuning and there was no fixing,” the album’s engineer, Al Schmitt, said in an online interview. “Everything is what it was.”

Trending

The arrangements are largely of a piece. The young, suave Sinatra found tragedy and melodrama in these songs, which he often sang as slowly as Dylan does. And for these songs, Dylan presents yet another changed voice: not the wrathful scrape of his recent albums, but a subdued, sustained tone. It’s still ragged; he is 73. But he carefully honors the melodies, even the trickier chromatic ones, and he fully inhabits the lyrics.

Not every song thrives under Dylan’s treatment. “Some Enchanted Evening” is stiff, and “Why Try to Change Me Now” denies the song’s humor. But even when it falters, “Shadows in the Night” maintains its singular mood: lovesick, haunted, suspended between an inconsolable present and all the regrets of the past.

— Jon Pareles,

New York Times

Vijay Iyer Trio

“BREAK STUFF”

ECM Records

The pianist Vijay Iyer publishes his compositions under the name Multiplicity Music, and that word goes to the heart of his enterprise as an artist. He’s led an important jazz-tradition trio for most of the last decade, but he’s also been writing music inspired by other traditions and functions, working with poets and emcees and string quartets. He doesn’t just improvise, he teaches a class in aesthetic and social theories of improvisation at Harvard; he makes music that not only intersects different strategies but lingers over the places of intersection.

The trio makes sense in a physical way, moving together as one unit. And it’s good how evolved that motion can sound in a piece as strange as “Hood,” a song inspired by the Detroit techno producer Robert Hood, because over the course of the record, the strength of the track takes the heat off Iyer’s versions of songs by his heroes (Thelonious Monk’s “Work,” Billy Strayhorn’s “Bloodcount,” John Coltrane’s “Countdown”). Those versions aren’t formal stunts — least of all the slow, elegant “Bloodcount.” They’re just more refined representations of the way Iyer and his trio perform in real time, with a rhythmic logic and a coordinated bustle of breaks and intersections. The band’s refractive language makes sense of whatever material it plays. You don’t hear the record and seize on its sense of rupture or argument. Instead, it sounds whole.

ON TOUR: Feb. 19 — The Shedd Institute, Eugene; www.theshedd.org or 541-434-7000. Feb. 20 — Winningstad Theatre, Portland; www.portlandjazzfestival.org.

— Ben Ratliff,

New York Times