’In Manchuria’ details a vanishing way of life

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 15, 2015

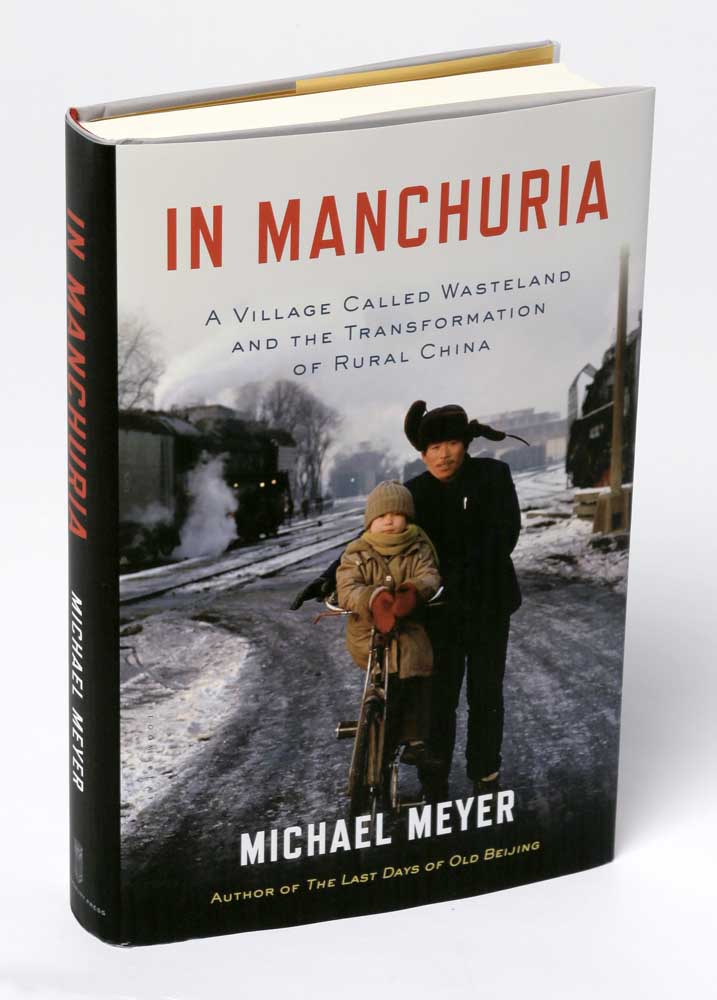

- Patricia Wall / The New York TimesWriter Michael Meyers new book "In Manchuria," which documents a changing rural China.

“In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China”by Michael Meyer (Bloomsbury, 365 pgs., $28)

In Chinese, the region that was once the cradle of the mighty Qing dynasty is today rather prosaically known as Dongbei, the Northeast. Home to 110 million people, it has smoggy cities and bitingly cold weather. It can seem drab or worse to a visitor. But Michael Meyer has a more refined sense of history and poetry, and with his new book, “In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China,” he seizes the opportunity to dig beneath the region’s gritty surfaces.

Meyer’s motivation for writing his book is simple and straightforward. “Since 2000, a quarter of China’s villages had died out, victims of migration or the redrawing of municipal borders,” as the country urbanizes, he notes early on, adding: “Before it vanished I wanted to experience a life that tourists, foreign students, and journalists (I had been, in order, all three) only viewed in passing.”

“In Manchuria” shifts back and forth among various genres. It is part travelogue, part sociological study, part reportage and part memoir, but it is also a love offering to Meyer’s wife, Frances, who grew up in the unfortunately named Wasteland, the village that Meyer chooses as his base near the start of this decade, and to the unborn son she is carrying by the time “In Manchuria” ends.

To tell his story, Meyer alternates between chapters that examine a broad historical canvas and those focused on his daily life in Wasteland. There he sleeps on a kang, a combination bed and stove heated by burning rice husks; uses a rudimentary outhouse and a public bathhouse; and tries to adjust to a place defined “by what was absent,” with “no local newspaper, no graveyards, no plaques, no library, no former mansions or battlefields.”

Along the way, he takes note of the few points of reference that might be familiar to Westerners, such as the movie “The Manchurian Candidate” or Puyi, emperor of the pre-World War II Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo and the subject of another well-known film, “The Last Emperor.” But his real goal is to burrow into a peasant society that would have been closed to him if not for his wife and her family.

Fascinating characters

“In Manchuria” is the second book by Meyer, whose work has also appeared in magazines and newspapers, including The New York Times. His first was “The Last Days of Old Beijing,” a well-received portrait of daily life in an ancient section of the city that is about to be razed in the run-up to the 2008 Olympics.

As a political and cultural center of 21 million people, Beijing offers an almost endless supply of fascinating characters and historical details. Wasteland, elevated to village status in 1956 and populated by a handful of families, is a more difficult subject, and Meyer responds to that challenge with mixed results.

Applying a method that worked well in “Last Days,” he has found colorful locals to anchor his narrative and capably captures the flavor of colloquial Chinese. Two residents seem especially noteworthy: the voluble Auntie Yi, a retired Communist Party cadre and a bit of a well-meaning snoop, and her taciturn brother San Jiu, who is rendered as the quintessential Chinese peasant, canny and deeply attuned to the interrelated cycles of nature, weather and the cultivation of rice.

But Meyer often strays from what is ostensibly his main subject, and sometimes it seems as if he is padding to compensate for the deficiencies that might be inherent in focusing on a tiny village. The review of Manchuria’s history and the excursions to the region’s main cities are clearly necessary, but a divagation about a lumberjack who claims to have been abducted by aliens and some of the detailed descriptions of the neglected museums he visited, seem only marginally relevant.

A year in Wasteland

Asserting that “perhaps no other region has exerted more influence on China across the last 400 years” than Manchuria also seems a bit of a stretch, meant to convince readers of the significance of his subject but likely to raise the eyebrows of Sinologists. And although it is true that Japan and Russia are central actors in the history of Manchuria, to say that “uniquely for a Chinese region, foreigners played a prominent role on its stage” plays down the experience of Xinjiang and Tibet.

But when Meyer turns to the transformation of the Chinese countryside in recent decades, he is able to use his experience in Wasteland to illuminate much larger trends. A commune in its early years, the village is, by the time he moves there, on its way to becoming a company town, yoked to a privately held enterprise called Eastern Fortune Rice. Founded in the late 1990s by a former chauffeur of the village chief, Eastern Fortune grows so rapidly that when Meyer arrived in Wasteland, it is urging — perhaps pushing is the better word — peasants to give up their land and homes and move into the modern apartment buildings going up near its processing plant. By the end of the book, Eastern Fortune’s managers are even talking about renaming the village after the company.

This clearly has the support of China’s Communist Party leaders. “You have to understand, this will be a nationwide trend,” the company’s general manager tells Meyer in between visits from top officials. “It can’t be stopped. (Chinese president) Xi Jinping has made developing the countryside his administration’s priority.”

As is so often the case in this book, San Jiu offers the most succinct assessment of the new situation. “Someone up here,” he says, raising his arm, “is always telling us down here what to do.” Meyer provides the unsaid subtext: “In feudal times, it was landlords. Then came cadres. Now there were managers.”

Meyer also has a knack for noticing amusingly incongruous details, and he employs that talent to full effect to convey the contradictions of contemporary China. He sips “a cup of Marxism brand instant coffee (‘God’s Favored Coffee!’ the package promised in English)”; notes that Harbin is a city with “a Wal-Mart bordering Stalin Park”; and, at winter’s peak, observes peasant girls who “belted out Lady Gaga songs” as they watched a basketball game in a frozen schoolyard, “tethered together with shared MP3 earbuds.”

After a year in Wasteland, Meyer was ready to move on, and he now divides his time between Singapore and Pittsburgh, where he teaches nonfiction writing. But his interlude in Manchuria clearly taught him many lessons, perhaps the most fundamental being this: “The countryside was romantic only to people who didn’t have to live there.”