What’s behind Central Oregon emergency alerts

Published 12:00 am Sunday, May 31, 2015

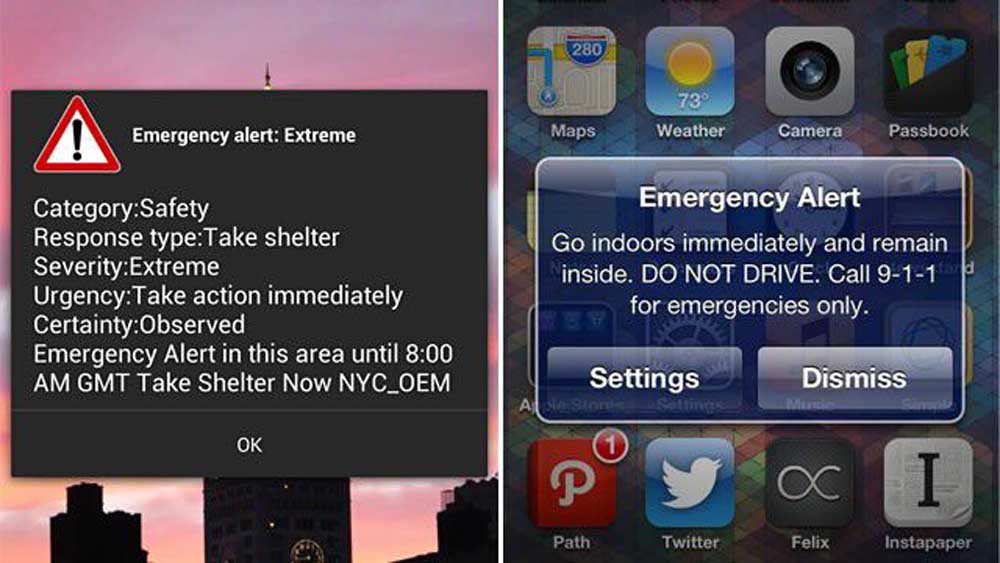

- FEMA / Submitted photoAn emergency alert sent to a phone.

Emergency alerts have come to pockets and purses near you.

Over the past couple of weeks warnings rattled cellphones around Central Oregon, alerting their owners to potential flash floods and abductions in the Northwest.

Trending

The alerts are examples of how local, state and federal agencies are trying to quickly connect people to emergency information. They represent ever evolving national alert systems developing with technology.

“The goal is to reach as many people as possible,” said Savannah Brehmer, spokeswoman at the regional Federal Emergency Management Agency office in Bothell, Washington.

Most major phone carriers have the ability to send out “wireless emergency alerts,” as they are referred to by federal agencies. And newer cellphones are set up to receive them.

Officials recommended people contact their carrier if their phone appears to not receive alerts.

The alerts look like text messages but do not become bogged down in the stream of notes from friends and family on many people’s phones. Instead they flash to the front of the phone. Some phones also put out a sound when they receive an alert.

“They want to get your attention,” said Michael Ryan, emergency manager for Crook County.

Trending

While the alerts show up on all sorts of phones, they should not lead to any additional costs appearing on bills.

“There is no cost to receive the alerts,” Brehmer said.

The three main kinds of alerts that may pop up on a cellphone are: Amber, or notifications about missing children; imminent threat, such as earthquakes, floods or deadly weather; and presidential, warnings from the nation’s top office.

Such alerts may come from federal agencies, said Sgt. Nathan Garibay, emergency services manager for the Deschutes County Sheriff’s Office. He said there are strict parameters to what information can be put into the alerts, which are limited to 90 characters — 50 less than a tweet.

“We are taking critical emergency information,” he said. “It is kind of the now or never type information,” such as about a wildfire bearing down on homes.

Along with being eye-catching, the alerts go to any phone in a particular area, rather than to a list of people who have registered for notices for a particular agency. For example, people from Central Oregon visiting the Midwest would see an alert on their phone if they were in an area where the National Weather Service issued a tornado warning. Cell towers relay the alert to all nearby phones.

“That is a big issue for us because we are an area that has such a high number of visitors,” Garibay said.

A recent alert in Central Oregon was for potential flash flooding on May 21 from the National Weather Service. The weather service will issue an alert if there is a danger to life or property, said Dennis Hull, a meteorologist with the agency in Pendleton. The office forecasts for Central Oregon.

“We issue (them) as often as we need to,” he said.

Alerts on cellphones expand on the familiar federal broadcast warning system, which sends out alerts over television and radio. Those messages may last up to two minutes, containing more information than those sent to cellphones, said Terry Cowan, general manager for a Christian music station in Bend. But they might not reach as many people as the cellphone alerts.

Given the limited length of cellphone alerts, emergency managers in Deschutes and Crook counties are looking at ways to improve how they can then follow up such messages or pass out more information, such as wildfire evacuation updates, that might not be spread using the federal wireless alert system.

While the counties have the ability to call landlines with such information, they are looking at ways to better connect, said Ryan, the Crook County emergency manager.

“In Central Oregon we don’t have a great mass-message system,” he said.

He and Garibay, his counterpart in Deschutes County, are looking at potential systems the counties could contract for yearly, including one that uses 26 points of contact for people who have registered — from texts to email to Instagram. Such systems range in cost depending on population, Ryan said, with Crook County likely facing a cost of up to $10,000 per year and Deschutes up to $35,000.

They get the word out, though.

“They allow you to get a lot of information out to the people you want to get it out to — and it does it very fast,” he said.

— Reporter: 541-617-7812, ddarling@bendbulletin.com