Narrator’s wry humor makes debut novel riveting read

Published 12:00 am Sunday, September 27, 2015

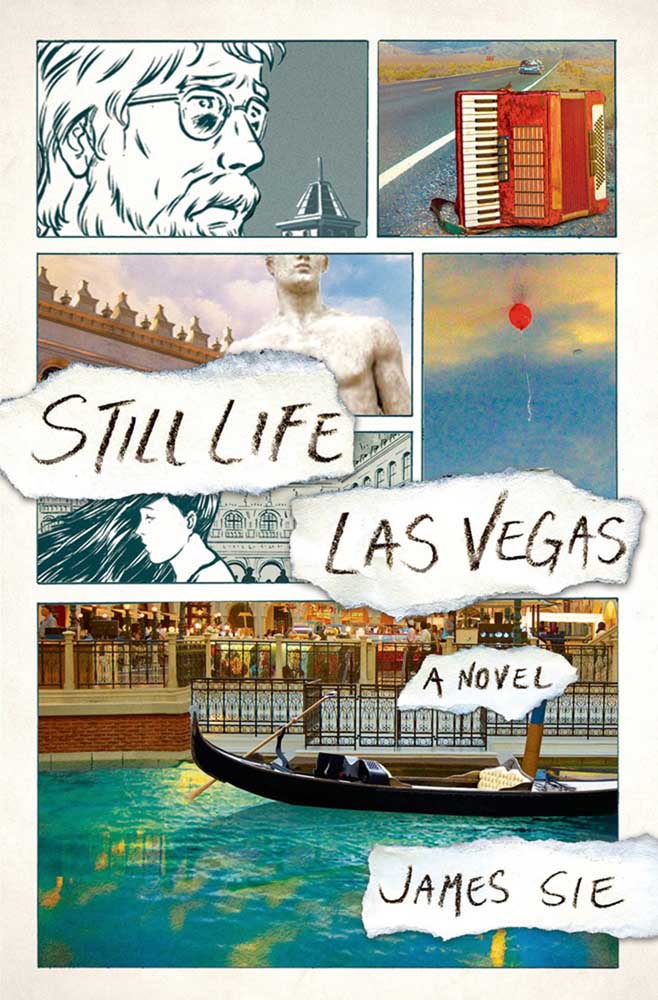

- "Still Life Las Vegas" by James Sie and Sungyoon Choi; St. Martins Press (336 pages, $26.99) (Macmillan Publishers)

“Still Life Las Vegas” by James Sie and Sungyoon Choi (St. Martin’s Press, 336 pages, $26.99)

“Still Life Las Vegas,” James Sie’s 326-page debut novel illustrated by Sungyoon Choi, isn’t easy to pin down. On one level, it’s an account of one boy’s coming of age. More precisely, it’s a tale of his coming to terms with his mother’s disappearance, his father’s crippling depression and his own sexuality, future and identity.

Trending

On another level, it’s a swirl of mythology and collective memory, a jumble of times and places overlaid, like half-dreamt palimpsests, on one young man’s circumscribed world. Palimpsest: that was the word that leapt most often into my mind as I delved into this account of the way tragedy reverberates across generations — an account whose emotional realism more than made up for its shortcomings in believability.

“Still Life,” in short, is a book about remembering. Each chapter bears no title, only a character, a place and a time. The characters are threefold, fourfold if you count a future version of narrator Walter, who introduces each section. The places are circumscribed. The times, meanwhile, are as hazy and co-referential as memory itself: “very long ago,” “later,” “earlier” being a few examples.

The story begins in Las Vegas, where we meet Walter. A high school senior, he’s graduated early to support his severely depressed father (Owen) by guiding tours of kitschy dioramas displaying the city’s history. He lives haunted by the disappearance of his mother, Emily, in that very city. Or rather, haunted by her disappearance post-suicide attempt, itself prompted by the death of her infant daughter.

“The idea was, back then, that if I could eliminate all the characteristics that weren’t her, I’d arrive, eventually, at a picture of who she was.” This is how Walter describes his childhood quest to find his mother. In lines like these (and there are a number of them), Sie deftly intertwines grieving with remembering. A presence is sketched (literally — artist Choi expertly renders Walter’s drawings of his lost mother) by tracing an accumulation of absences around its edges.

Yet life pulls Walter onward; even as he comes to terms with his past, he must reckon with his future. As winter wears into spring, he finds himself pulled into a romance with Chrysto, an alluring Greek man who longs to escape a tragic past of his own. The relationship forces Walter to confront his future: a confrontation that demands he move beyond the losses that have thus far defined him.

All this to say: At rendering matters of grief and of memory, Sie and Choi are masterful. So too do they craft a gripping narrative. We learn of the tragedy itself only slowly, in images that bring it to life. Slower still do we discover that many of the stories Walter has lived with were half-invented. Instead, it is the memory — or rather, the act of making that memory — that readers are introduced to first.

Trending

Laid out so explicitly in writing, all this stuff about memory and tragedy and narrative can seem precious. At times, this is true of Sie’s book, too. By its concluding chapters, a less charitable reader might grow weary of the tragedy, endlessly repeated; or of Owen’s depression, seemingly incurable. That reader will also encounter plot points that strain credulity: take, for instance, Chrysto’s ability to stand still for hours on end for his job posing as a statue at a local casino.

For me, though? Walter’s wry humor and Sie’s emotional realism ensured a riveting read, if not an entirely realistic one. Racing through it felt like a dream — at times unpleasant, occasionally hard to believe, but always vivid and immersive.