Snakebite victims face big hospital bills

Published 12:00 am Thursday, October 8, 2015

- Snakebite victims face big hospital bills

Three years ago this month Marsha Phelps, of Sisters, became one of the very few people in Oregon to be bitten by a rattlesnake.

She was air-lifted from the Crooked River Ranch area to St. Charles Bend, where she received four vials of antivenom and spent a night under observation. The juvenile rattler’s fangs struck just the tip of her finger, but the swelling had progressed up the length of her arm.

Back at home, she felt tired for a couple of weeks. Over the next year, her lymph glands would swell. “Otherwise, I think I got off lightly,” said Phelps, who’d seen horrific photos of snakebite victims online.

Her hospital bill also was relatively mild for a snakebite: about $25,000, Phelps recalled.

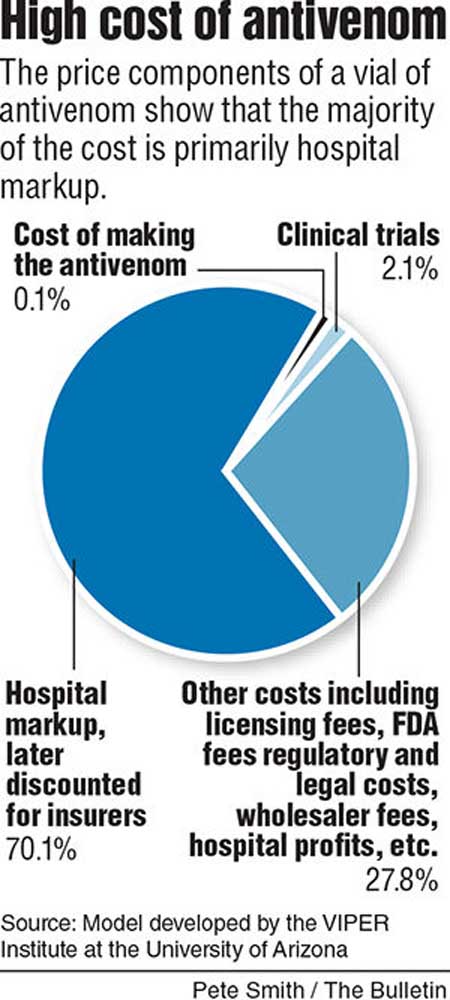

Snakebites are notoriously expensive to treat, and an Arizona researcher has found that the antivenom itself accounts for just a sliver of those bills. The largest factor is hospital mark-up before insurance discounts, according to a forthcoming paper by Dr. Leslie Boyer, founding director of the VIPER Institute at University of Arizona, which studies the effects of venom on humans.

“This analysis demonstrates that well over half of the astonishing hospital charges reported in the lay media are not true costs at all, but are instead attributable to the idiosyncrasies of the U.S. health care finance system,” Boyer wrote in an article to be published by the American Journal of Medicine in February. The accepted version was published online in August.

Even after big mark-ups, not all hospitals earn a profit on antivenom, Boyer said. A rural community hospital that doesn’t have much clout with insurance networks could end up losing $1,000 per vial after the insurance discount.

St. Charles Health System treated five snakebites and 28 spider bites at hospitals in Bend, Madras, Redmond and Prineville over a one-year period ending Sept. 1.

The hospital charges $6,023.44 cents per vial of snake antivenom and says it usually takes four to five vials to treat a bite. Spider antivenom costs $60.68 per vial and treatment also requires four to five vials.

The only poisonous snake in the wild of Oregon is the western rattlesnake, but it’s hard to determine how many people they bite. Anywhere from 35 to 55 snakebites are reported each year to the Oregon Poison Center at Oregon Health and Science University. That count includes bites from domestic pets and nonpoisonous snakes.

Phelps said she was always curious about how much her insurance company paid for the antivenom. One of the three friends who was hiking with her the day she was bitten is a nurse who told her the typical wholesale cost is $2,000 per vial.

“My insurance covered everything, but it was quite spendy,” Phelps said.

Treating snakebites can require 20 vials of antivenom, Boyer said, so it’s easy to see how a bite could result in a hospital bill over $100,000.

Boyer’s research team was involved in developing two snake antivenoms, CroFab and Anavip, and conducted clinical trials on the first FDA-approved scorpion antivenom, Anascorp.

Like most doctors, she tried to keep a safe distance from the business side of the drugs she researched. But she was dismayed to learn after Anascorp’s release that the wholesale cost was so high that hospitals weren’t using it. With the antivenom, the victim of a scorpion sting could go home from the ER in an hour, she said, but hospitals found it was cheaper to keep a victim for two days while the poison wore off.

Then Boyer started noticing news articles about enormous hospital bills for snake antivenom. Boyer said, “It’s very easy to wave your hands in the air and say, ‘somebody’s greedy.’”

Instead, she started contacting her many connections in the antivenin industry to gather cost data. She called everyone from snake milkers to the people who acquire drugs for hospital pharmacies. She created a model of a bill for a hypothetical scorpion antivenin, which would be $14,624. Seventy percent of that is attributable to hospital mark-up, according to Boyer.

The next-largest category of expenses would be a catch-all that includes miscellaneous profits, marketing costs and legal fees, Boyer said.

The cost of actually making the drug, from research and development to freeze-drying and bottling, would be $14, or 0.1 percent of the cost. That’s despite the fact that making antivenom requires injecting horses, or some other farm animal, with the poison and then harvesting and purifying the antibodies they produce.

Although Boyer used arthopod antivenom as the model for her study, she thinks her findings apply to snake antivenom. The dollar figures would be different, she said, but the proportion of bills attributable to hospital mark-up would be the same.

— Reporter: 541-617-7860, kmclaughlin@bendbulletin.com