‘Caped Crusade’ and Batman’s reach beyond — gasp! — comic book lore

Published 12:00 am Sunday, March 27, 2016

- ‘Caped Crusade’ and Batman’s reach beyond — gasp! — comic book lore

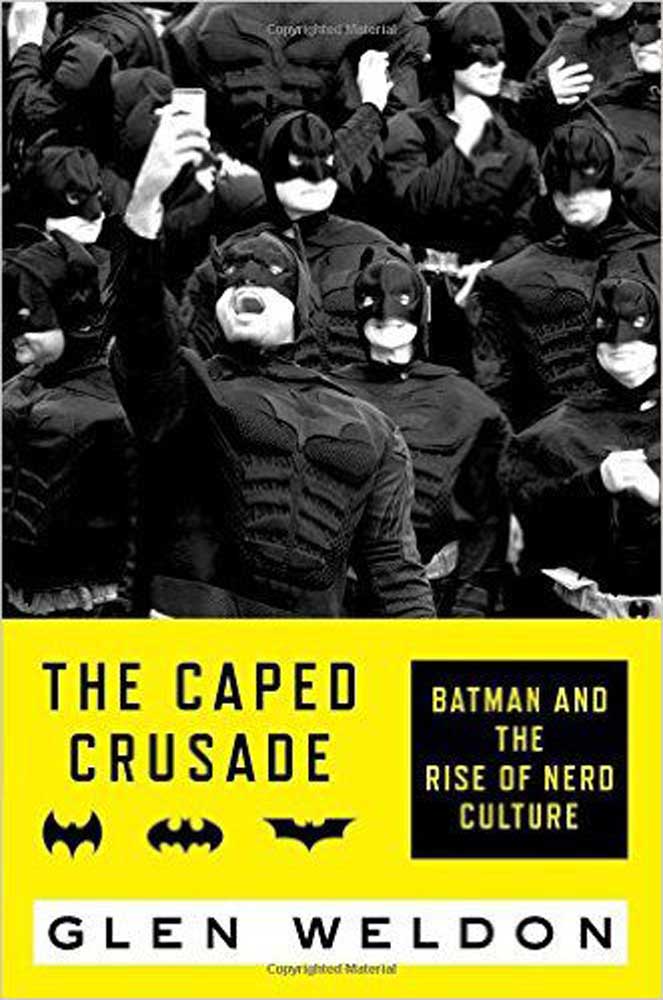

“The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture” by Glen Weldon (Simon & Schuster, 324 pages, $26)

A few days ago, I would have said the world could be divided into two types of people: Those who think deeply about the hermeneutics of Batman, and those who do not. That was before reading Glen Weldon’s “The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture.” I’m now of the mind that there’s a continuum from normals to nerds. I land somewhere in the middle.

Trending

The book is, in many respects, a roaring getaway car of guilty pleasures — film gossip, comic-book esoterica, hilarious tales of nerd rage. (For a while, the most dangerous place in Hollywood, clearly, was the space between a fanboy and Joel Schumacher, who had the audacity to add nipples to Batman’s rubber costume in “Batman Forever.”)

Weldon, a panelist on NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour and the author of “Superman: The Unauthorized Biography,” writes with humor and Day-Glo élan. The earliest Batman comics are “a crude, four-color slumgullion of borrowed ideas and stolen art”; the Joker wears “riverboat-gambler couture.” The author is also a cheerful reverse snob, celebrating the camp exuberance of the 1960s Batman TV series that so many purists loathe. “The mere existence of Adam West’s Batman,” he writes, “breezily yet effectively rejects the notion that the only valid Batman is a grim, gritty badass.”

It’s a point of view that would certainly get him tossed out of Comic Book Guy’s shop on “The Simpsons.” He doesn’t care. At the 2013 Comic-Con, Weldon, then 45, waited an hour and 45 minutes for the privilege of spending 60 bucks on a plastic replica of the TV show’s Batmobile.

But to make it through “The Caped Crusade” in one piece, I’m afraid, you need to care an awful lot about Batman minutiae. I’m not just talking about relishing the details of how the cape has evolved, or when the bat insignia acquired a yellow halo (Detective Comics No. 327, May 1964). I mean you also have to maneuver through a few too many plot recapitulations, follow every tortuous twist in failed Batman scripts and keep track of a lengthy roster of artists and illustrators who collaborated across multiple decades and hundreds of issues. It’s like doing some weird, literary version of the Batusi.

I should make clear, though, that I come to “The Caped Crusade” without a long list of fangirl bona fides, which may compromise my patience a bit. But I am Bat-curious.

Yet there were sections of “The Caped Crusade” that only flickeringly, fitfully held my attention. In some ways, Weldon faces the same dilemma the directors Tim Burton, Joel Schumacher, Christopher Nolan and Zack Snyder did: When you bring the story of Batman to the masses, who is it for? The normals or the nerds?

Trending

Weldon starts with the basic elements of Batman’s appeal: Unlike other action heroes, he has no superpowers (though he does have an enormous trust fund, which, in the author’s estimation, does set him apart from most mortals); his parents were murdered in front of him as a child, which drove him to swear an oath so idealistic and melodramatic “that only a kid could make it” — he’d spend the rest of his life fighting criminals.

But beware of loving any one particular version of Batman too much. That’s the true lesson I learned in “The Caped Crusade.” It’s a commitment to having your heart broken. Batman will always be subjected to the slings and arrows of outrageous appropriations. By Hollywood. By McDonald’s. By Lego. By Adam West nostalgists, by fan fiction writers, by — gasp! — girls and queer theorists. “There is Batman the character,” Weldon writes, “and Batman the idea.” The idea is always there for the taking.