Want a home-cooked meal? Go to school.

Published 12:00 am Thursday, September 1, 2016

- Want a home-cooked meal? Go to school.

A tour through the Bend High School kitchen winds past cooling trays of fresh-baked whole wheat pizza crusts, a cook placing homemade black bean burgers into storage containers and — just outside the back door — a smoker filled with pork butts.

Hardly the frozen mystery meat of years past.

Trending

Whether it’s California sushi rolls, BBQ pork sandwiches or Italian stromboli, each day of the Bend-La Pine School District’s September lunch menus feature at least one entree made from scratch — usually a couple. All 16,000 to 17,000 lunches served daily are typically made right here in the sprawling Bend High kitchen and then carted off to their respective schools.

Schools’ increasing dedication to making lunches from scratch is driven by a few factors. One: Kids are changing. Like adults, they’re increasingly interested in learning about what’s in their food and rejecting foods that come frozen in boxes. They’re also used to going to places like Chipotle or Subway getting things exactly as they want, something today’s schools have learned to accommodate.

“This generation, Gen Z, they definitely want some customization,” said Wesley Delbridge, a registered dietitian in the Phoenix metro area and the nutrition director for his local school district.

But there’s another factor driving this: federal regulations aimed at improving kids’ nutrition. The Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 championed by first lady Michelle Obama sets limits on the amount of sodium, calories and saturated fat school breakfasts, lunches and snacks can contain, and it mandates that schools offer a variety of different vegetables and fruits and swap out white bread for whole wheat.

Frozen, processed foods tend to contain loads of sodium and calories, and making foods from scratch tends to cut down on that.

“In order to get the sodium down, you’ve got to make more scratch meals,” said Donna Martin, a dietitian and School Nutrition Program director in Burke County, Georgia. “That’s the best way to control the sodium, is to put more herbs and spices in there that are not salt. You’re seeing that trend definitely.”

Trending

Martin, president-elect of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, said her schools have recently added things like homemade hummus, veggie burgers and stir fries, all of which have gone over well with students.

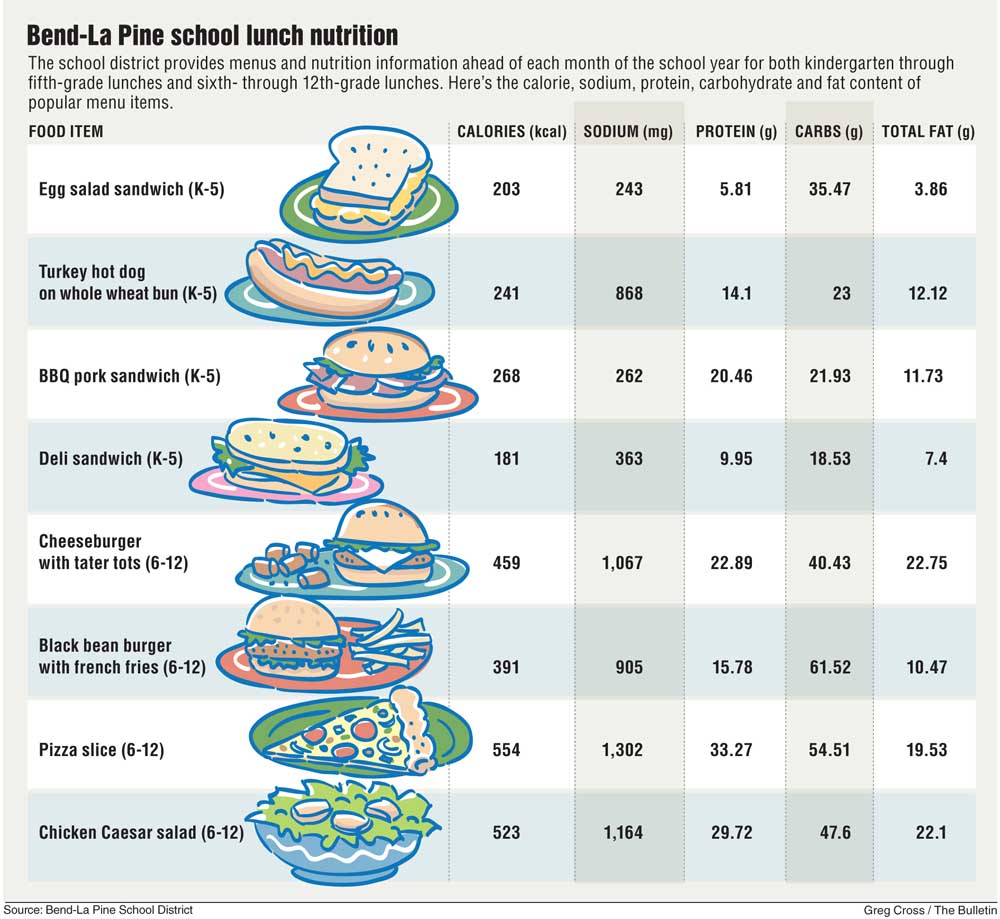

Federal rules require schools limit their kindergarten through fifth-grade lunches to a maximum of 650 calories when averaged over the course of a week.

For the first week of the upcoming school year, which runs Sept. 7-13, the Bend-La Pine district’s lunches for those grades average 570 calories, according to nutrition data provided by the district. For grades six through 12, however, calories average 949 that week, surpassing the federal limits of 700 for grades six through eight and 850 for nine through 12.

Katrina Wiest, the district’s wellness specialist, pointed out that not all kids will eat all of the servings of food used to calculate the average calories per lunch.

The district is also struggling with the federal sodium guidelines. While it falls well below the 1,230 milligram limit for kindergarten through fifth-grade lunches — coming in at 850 milligrams — it surpasses the limit for the older kids. The law limits sodium to 1,420 milligrams for grades six through 12, and the district’s average for its first week is 1,886 milligrams.

“Sodium is a challenge,” Wiest said.

A slice of pizza for the sixth- through 12th-graders contains 1,302 milligrams of sodium, for example, which Wiest said is because of the cheese.

“How do you make cheese with no salt?” she said.

Not all items have that much sodium, though. The district’s homemade chicken pot pie has only 484 milligrams. A hummus plate has 406 milligrams. A chicken Caesar salad, on the other hand, contains 1,164 milligrams. A deli sandwich — also made daily at the schools — contains 1,074.

Those limits are set to get even stricter in 2017 and again in 2022, when they get as low as 640 milligrams for the youngest students. Those limits have been widely criticized by school districts and advocates as being unrealistic. The Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act is currently up for reauthorization, and language in a Senate bill being debated in Congress would postpone those limits for two additional years, said Diane Pratt-Heavner, a spokeswoman for the School Nutrition Association, a professional group that represents school lunch workers.

When sodium levels get that low, it becomes a balancing act between providing healthy lunches while also ensuring kids will still eat them.

“We feel if they lower those even more, it’s just not going to taste good,” Wiest said. “There is a threshold.”

At the end of the day, school lunch programs can be considered nonprofit businesses onto themselves, which need customers — students — to stay afloat, said Terry Cashman, Bend-La Pine’s director of child nutrition and operations.

“Our customers are the kids, the students, and if we don’t have them eating with us then, yeah, we may suffer as a business,” he said. “So the more kids that eat with us, the better chances of our budget being great enough that we can provide offerings to the kids.”

In the Bend-La Pine district, slightly more than half of students take school lunch. That percentage is highest in the elementary schools and lowest in the high schools, where students have the option of leaving school for lunch. Over the past two years, the district has seen a roughly 8 percent increase in the number of lunches purchased, Cashman said.

Delbridge, the Phoenix area dietitian, said he also opposes the stricter sodium standards in the future, although he supports the current ones. If the places kids get their meals outside of school, like restaurants and stores, don’t lower their sodium contents, then the food at schools will seem bland, and kids won’t eat it.

“They’re customers I have to win over every day,” said Delbridge, who also serves as a spokesman for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

The federal rules also require schools to limit the saturated fat content in their lunches to 10 percent of total calories, which the Bend-La Pine district achieves, according to the nutrition data provided. School lunches can’t contain any trans fat under the federal guidelines; Bend schools have complied.

Also under the federal guidelines, all grains served in school lunch must be at least 51 percent whole grain, including things like pizza crust and hot dog buns. To do that, Wiest said the district buys a variety of whole wheat flour that appears white from a mill in Junction City. Schools initially baked with traditional whole wheat flour, but it didn’t go over well, she said.

“We had a revolt on our hands,” she said.

The federal regulations also apply to things likes cookies and chips served in a la carte areas of cafeterias, vending machines and fundraisers during school hours. Snacks must also be whole grain rich and can’t include more than 200 calories, 350 for an entree.

Schools also have to serve students more vegetables and fruits at breakfast and lunch times. During both meals, students are required to take at least one half cup serving of a vegetable or fruit. Vegetable choices at lunch must include weekly offerings of dark leafy greens, legumes and red or orange vegetables.

To make sure kids take those items, fruit and vegetable monitors check students’ trays after they pass by those sections of the lunch lines, Cashman said.

“If they don’t have anything, we remind them to go back and get some,” he said.

To make sure food isn’t wasted, cafeterias have ‘No thank you’ bins where students place their unwanted produce, which can then be washed and reused, Cashman said.

All Bend-La Pine schools offer daily vegetarian and gluten-free lunches, Wiest said.

A lot goes into planning the district’s meals, Cashman said. The district buys many of its vegetables, fruits and meats from local farmers who agree to supply their products at special prices. And despite all of the regulations around foods’ nutritional content the district must meet, Cashman said it’s also important that it taste good.

He added, “We want to make sure that our kids get the best fuel for success in the classroom.”

— Reporter: 541-383-0304,

tbannow@bendbulletin.com