Oregon’s pinot harvest is underway

Published 12:00 am Thursday, September 8, 2016

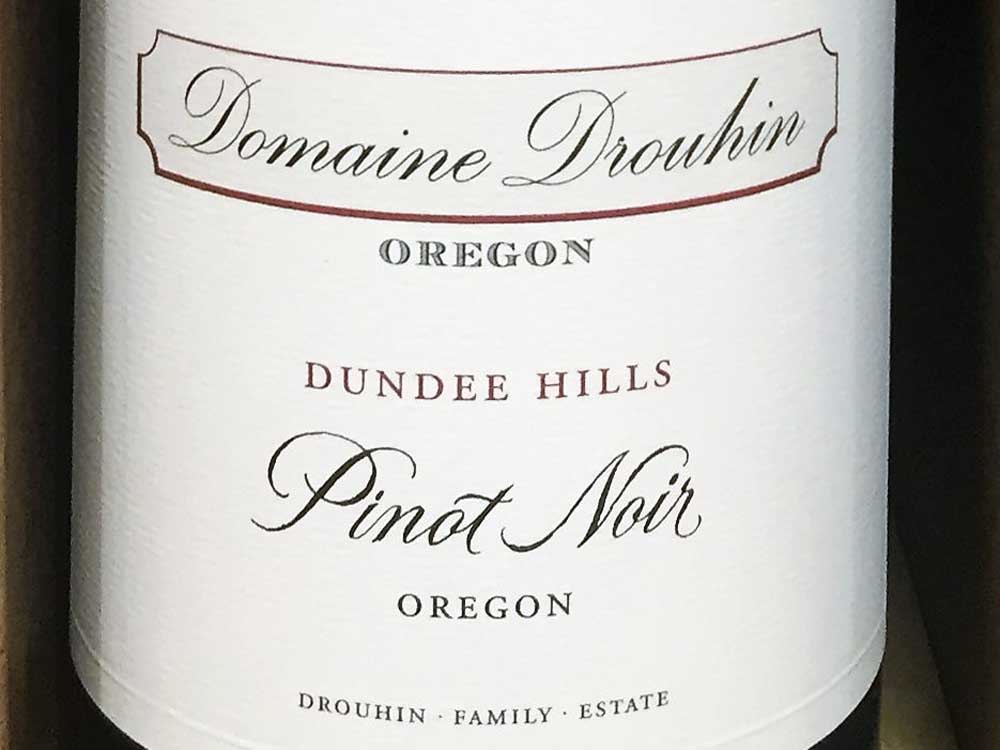

- Submitted photoThe 2014 Dundee Hills pinot noir from Domaine Drouhin ($43.95) is one of many outstanding Willamette Valley pinots. The French-style red has notes of dark cherry and blackberry, framed by light tannins that can be aged for 10 to 12 years.

September is harvest month in Oregon’s Willamette Valley wine country. While the picking season may extend until the first fall rains of October, the vast majority of pinot noir and other grapes are plucked from the vines this month.

More than 350 of the state’s 500-plus wineries are in the Willamette Valley, where more than 20,000 acres are committed to the growing of grapes. The first of those vines were planted in the Dundee Hills in 1965.

Trending

There were only 200 acres in grapes in 1972, after the Sokol Blosser family planted its initial vines. But after pinot noir from The Eyrie Winery placed among the top three wines in the world in a French “Olympiad” in 1979, the Dundee Hills gained an international reputation.

Pinot noir is a temperamental, thin-skinned grape varietal that requires a particular geography to grow successfully. France’s Burgundy, its native region, fills the bill. So, too, does the Willamette Valley, which happens to lie in the same latitude with a similar seasonal climate. The Dundee Hills terroir, characterized by volcanic-ash soil and generally southeast-facing slopes, arguably produces its best wines.

Domaine Drouhin Oregon

Robert Drouhin suspected that might be the case when he purchased acreage in 1987 and, two years later, established Domaine Drouhin Oregon.

The scion of a longtime family of vignerons in Beaune, France, Drouhin had sent his daughter, Véronique, to study winemaking in Oregon the previous year. In 1988, father and daughter planted eight acres with Pommard clones of the pinot grape; the following year, they built Oregon’s first state-of-the-art, gravity-flow winery. Their first pinot noir, released in 1991, was immediately acclaimed for its silky elegance.

On a recent morning, I stood with assistant winemaker Arron Bell amid the 126 acres of vineyards at Domaine Drouhin Oregon, as he eyed a crew of about 20 laborers racing through the vines as a paid-by-the-bucket brigade.

Trending

The French Drouhins spend most of the year in their Burgundy home, so Bell serves as their eyes and ears at the Oregon estate. “I just implement what (Véronique) wants done,” he said. “But that’s not too hard: Domaine Drouhin’s philosophy is to do as little as possible, to keep our wines as natural as we can.”

Although many different styles of grapes are grown in the Willamette Valley, pinot is king. Domaine Drouhin Oregon produces only two wine varietals: Pinot noir (about 15,000 cases a year) and chardonnay (about 3,000 cases). While Drouhin’s chardonnay is aged 50 percent in French oak, 50 percent in stainless steel, Bell said, pinot spends 14 months in an oaken barrel and another year and a half in the bottle before it is released for public consumption.

Sokol Blosser

The Sokol Blosser winery — named for its founders, Bill and Susan Sokol Blosser — was one of Oregon’s first when it opened in 1971. Its winery building and tasting room were the first in the state built for those specific purposes in 1978, Brown said. Three years ago, it added a beautiful new tasting room that is the pride of Oregon’s Wine Country.

By Oregon standards, Sokol Blosser’s annual production of 80,000 cases is moderate, said Michael Kelly Brown, vice president of consumer sales. Ten thousand cases of estate pinot noir, its specialty, come entirely from grapes grown on its own 90 acres of vineyards. But its numerous blends — notably Evolution, a combination of several white grapes, and Evolution Red — are made with grapes purchased from other growers.

Sokol Blosser’s barrel room was the first Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design-certified winery building in the world when it was completed in 2002. Humidity misted above hundreds of oak barrels as Brown and I walked beneath the sod roof.

“Every barrel in this cellar has a different chart, so to speak,” said Brown. “Each one is designated by individual block, age, terroir and cooperage.

“This is where the art of a winemaker comes in. The barrel room is a winemaker’s palate. He can take a little from this barrel, a little from that, a little from the next, in blending the grapes and clones that he wants.”

Stoller Family Estate

In the same neighborhood is the Stoller Family Estate, whose 180 planted acres comprise the largest contiguous vineyards in the Dundee Hills. Its handsome tasting room, opened in 2012, boasts cathedrallike windows that frame a west-facing view of the grapevines.

“This was originally Oregon’s largest turkey farm,” winemaker Melissa Burr said. “Bill Stoller bought it from his uncle in the late 1980s and planted a 10-acre vineyard. Now we produce about 17,000 cases of wine annually.”

Most of the production, as with other Dundee Hills wineries, is pinot noir and chardonnay, along with a small amount of riesling, said Burr. But she has planted experimental tempranillo and syrah for her own wines, she said, and a small amount of pinot gris and pinot blanc are produced for sale to other producers.

“Our pinot noir is cold-soaked for three to seven days,” Burr said, “allowing color to be pulled from the stems before it is sorted and de-stemmed. Only then do we start fermenting. After the grapes settle, we age the juice in barrels for 10½ months.”

Pinot noir, she said, is an unusually fickle grape. “There’s not a lot of room for error,” she said. “It doesn’t like extreme heat, and it’s so delicate that if there’s a heavy rain, its thin skin can split. What’s more, it’s financially challenging.”

Burr was studying to become a naturopathic physician when life took a meander and she wound up making a different kind of medicine, the kind sold in 750-milliliter bottles. In 2016, she is celebrating her 14th vintage.

In the barrel room, Burr described the number coding system that identifies separate pinot clones, which may be blended or used by themselves. Pinot noir, she said, will remain in the bottle for two years before its release.

— John Gottberg Anderson specializes in Northwest wines. His column appears in GO! every other week. He also writes for our food section.