Arnold Palmer was a pitchman who was ahead of his time

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, September 28, 2016

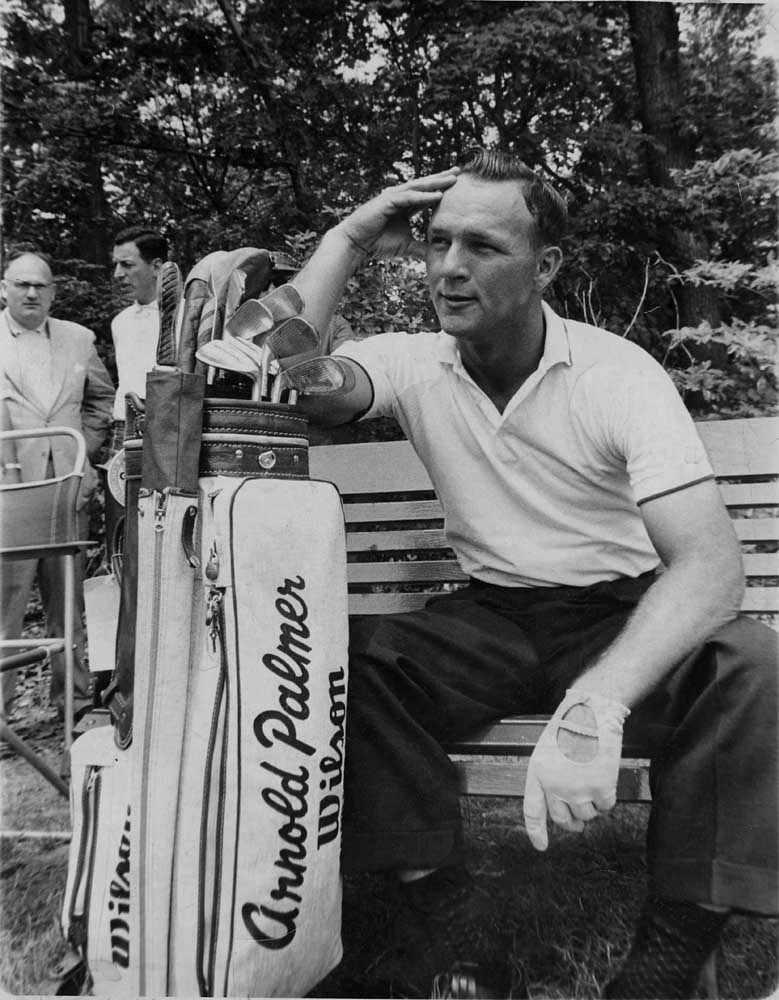

- Ernie Sisto / The New York Times file photoArnold Palmer, who died Sunday at 87, hawked nearly 50 products over a half-century and, in many ways, serves as a model for the modern entrepreneurial athlete.

In a grainy black-and-white 1968 television commercial, Arnold Palmer steers a Mercury Monterey up to a golf course, nodding approvingly at the coupe’s smooth handling. A few years later, Palmer was driving up to another course, this time in color, in a flashy Cadillac El Dorado.

In the 1980s, Palmer, long past his golfing prime, pitched Pennzoil motor oil and Paine Webber brokerage services and appeared alongside O.J. Simpson in ads for Hertz rental cars. And just last year, Palmer starred in a commercial for the blood thinner Xarelto, earnestly pitching the drug in a bright pink shirt on a lush green course.

For all his success on the golf course, where he won seven major titles, Palmer’s most enduring influence may be on the multibillion-dollar sports marketing industry.

A pioneering businessman on two fronts, Palmer, who died Sunday at 87, in many ways created the template for the modern entrepreneurial athlete.

A ubiquitous pitchman for more than half a century, he hawked nearly 50 products and services, from Johnston & Murphy shoes to Ketel One vodka, transforming the celebrity endorsement from a novelty to an industry.

At the same time, he carefully cultivated his personal brand, forming his own company, creating a logo, selling products and equipment adorned with his signature, and paving the way for modern stars with diverse business interests like Serena Williams and LeBron James.

“He was the pioneer,” said Bob Williams, chief executive at Burns Entertainment & Sports Marketing, which represents brands who hire celebrities for endorsements. “He was the first celebrity in the sports world to have a marketing agent.”

Palmer earned an estimated $875 million through endorsements, appearances, licensing and golf course design, according to Forbes. That places him behind only Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods in lifetime earnings for athlete-pitchmen. With many products bearing his name still selling briskly, Palmer’s estate will keep making millions for years to come.

When Palmer began playing golf professionally in the 1950s, few athletes were endorsing products, and those who were usually did so for nominal fees and free samples, often cigarettes.

Then in 1958, Mark McCormack, a golf fan with a hunch that professional athletes could be stars off the field as well, began pitching golfers on the idea of letting him represent them in their business dealings.

Palmer was reluctant at first.

“I wasn’t looking for an agent,” Palmer said in a recent book “Players: The Story of Sports and Money, and the Visionaries Who Fought to Create a Revolution,” by Matthew Futterman. “I had my wife. She was handling everything.”

But in fall of 1959, Palmer agreed to work with McCormack on an exclusive basis. McCormack wanted to sign a contract, but Palmer preferred a handshake.

That handshake, legend has it, was the foundation of one of the most lucrative partnerships in the history of sports. McCormack would go on to establish IMG, the powerhouse sports marketing company, which merged with William Morris Endeavor in 2013. And from the start, Palmer was among his most important stars.

As Palmer’s playing career wound down in the mid-1960s, his commercial activities ramped up. Soon Palmer was endorsing Golf Magazine, United Airlines and Bausch & Lomb. Not all endorsements were hits. When Palmer became the face of a dry cleaner, it fell flat. “It wasn’t always the Midas touch,” Alastair Johnston, Palmer’s longtime agent at IMG, said in an interview.

But before long, Palmer was being sought out by companies looking for a wholesome face to represent their brands.

“He established the sports marketing industry as we knew it,” Johnston said. “It became a much more sophisticated exercise. It became a real business with real money.”

Palmer’s popularity coincided with the rise of television, a medium that allowed him to vastly expand his audience beyond golf fans.

“It brought him into people’s living room, whether he was endorsing tomato ketchup or airlines,” Johnston said.

Thanks to Palmer’s celebrity, McCormack was able to quickly corner the market for athlete endorsements, attracting other stars and divining profitable pricing models for a nascent business.

“What Mark was able to do is something that is painfully obvious now: He was able to establish rate cards and costs,” Johnston said. “That was really how Arnold helped to start IMG. It made IMG the biggest single force in the world of sports marketing. Others who would try to compete would either underprice or overprice.”

Eventually, Palmer received a stake in IMG.

Through his namesake company, Palmer would go on to market golf clubs and clothing, and to serve as a designer for golf courses around the world. He became an investor in everything from the Golf Channel to real estate that was adjacent to courses he designed.

“What he did, creating a brand unto himself, was the blueprint for everyone who came after him, whether it be LeBron, or Jordan or Tiger Woods,” Futterman, the author of “Players” and a reporter at The Wall Street Journal, said.