Concerns remain over inappropriate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics

Published 12:00 am Thursday, November 24, 2016

- Concerns remain over inappropriate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics

Oregon has made progress in curbing inappropriate antibiotic use, but too many doctors still prescribe antibiotics when they are ineffective or choose more broadly acting antibiotics when a more targeted medication will do.

A report issued by the Oregon Health Authority last week found that prescriptions for oral antibiotics in doctors’ offices and outpatient clinics dropped 29 percent since 2008, including an 8 percent drop from 2014 to 2015.

But prescribing rates remained too high for conditions such as colds or bronchitis in adults, and for ear infections in children.

“Bronchitis is one that’s almost always a virus,” said Dr. Ann Thomas, medical director of the agency’s Alliance Working For Antibiotic Resistance Education. “Unless you have a lung disease, COPD for instance, that one really shouldn’t be treated.”

Yet the data showed about 50 percent of patients with bronchitis received an antibiotic.

“That number should be less than 5,” Thomas said.

The agency began collecting data on antibiotic prescriptions from health insurers in 2008, and later added prescribing data from a state database of claims from public and private insurance plans. The data only captures the number of prescriptions filled, and not the actual number of prescriptions written by physicians.

Prescribing rates dropped more for children than adults, although antibiotic scripts remained a more common occurrence in pediatric settings than for adults. Antibiotic prescriptions for ear infections in children dropped from 95.6 per 1,000 kids in 2011, to 74.1 per 1,000 in 2013, a 23 percent reduction. But given that many ear infections are caused by viruses, which cannot be treated with antibiotics, those numbers may still be too high.

Dr. Logan Clausen, medical director at Central Oregon Pediatric Associates in Bend, says the only way to tell whether a child has a bacterial ear infection is for a doctor to look in the ear.

“No family would be able to see it,” she said. “If they take the time out of their busy schedules to come in and have the check done just to hear us say, ‘There’s nothing we can do, it’s a virus,’ I think that sometimes a parent can feel frustrated.”

Pediatricians may then feel the pressure to prescribe something to keep the family happy.

Choosing wisely

The report also raised concerns about the overuse of so-called broad-spectrum antibiotics, which affect a wide range of bacteria in the body.

“That covers more bacteria so it increases the chance that some bacteria in your body will become resistant, plus what we see is that it just wipes out the healthy flora in your gut,” Thomas said. “That predisposes you to a condition called clostridium difficile, a very severe form of bacterial diarrhea.”

In general, physicians want to prescribe an antibiotic that specifically targets the bacterium causing the illness. It’s only when doctors aren’t sure which bacterium is causing the problem or no narrow-spectrum antibiotic will be effective that they should turn to a broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Even though antibiotics are rarely called for to treat bronchitis, 49 percent of patients with that diagnosis filled a prescription for an antibiotic and 69 percent of those prescriptions were for the broad-spectrum antibiotic azithromycin. The antibiotic is made by several brand name and generic manufacturers but may be most familiar to patients as a “Z-pak,” a convenient five-day pill regimen with half the doses of other antibiotics.

It’s also much easier for physicians to prescribe.

“All you have to do is scrawl that on (the prescription pad) and take it to the pharmacy,” said Dr. Dimitri Drekonja, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota and an infectious disease specialist at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System. “The other ones, you have to scrawl out the drug name, the dose, how many days. Z-pak has been a victory of quick marketing.”

Where most antibiotics have long and complicated names that patients have trouble remembering, doctors say patients routinely ask for a Z-pak by name.

“There’s definitely data that shows that when a clinician thinks that a patient or a caregiver is expecting an antibiotic and can name that by name, we’re going to try to meet that expectation,” said Dr. Jason Newland, associate professor of pediatrics at Washington University in St. Louis and director of the antimicrobial stewardship program at St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

That may be due in part to an increasing reliance on customer satisfaction surveys as a quality metric with financial penalties for providers who score poorly. Doctors are also concerned that if they don’t give patients what they want, those patients will go elsewhere for care.

“There’s minute clinics, urgent care, telehealth,” Newland said. “If a patient leaves your office and says, ‘I wanted something,’ they get on their phone and go to an internet site and they can get a prescription over their phone. That’s absurd.”

Fewer options

Public health officials have been focusing on reducing inappropriate antibiotic use for more than a decade, as overuse has lead to an increasing number of bacteria becoming resistant to antibiotics. In some areas of the country, doctors have encountered bacteria for which no antibiotic remains effective.

Clinicians are increasingly finding themselves with limited options for treating infections. Clausen said many of COPA’s patients have allergies to certain first-line antibiotics, especially amoxicillin, which forces them to use a second-line antibiotic. For younger children, doctors are limited to those antibiotics that are available in liquid form.

“There are some medicines out there that taste so terrible that getting through 10 days of a course is really challenging,” Clausen said. “If you complete only four days of your 10-day course, that also leads to antibiotic resistance.”

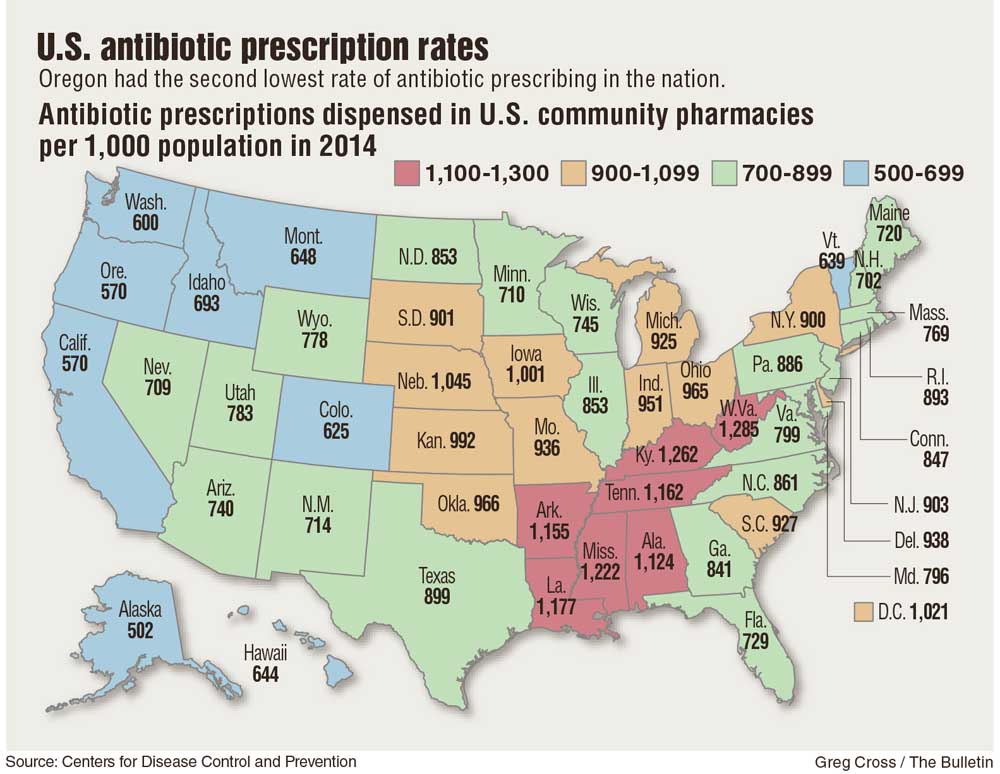

In many ways, Oregon has become a model state in terms of antibiotic stewardship. According to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, only Alaska has a lower per capita rate of antibiotic prescribing. Newland said he knows of no other state that has established a database to track prescribing the way Oregon has.

“You’ve seen continued reduction, but it’s not where we want it yet.” Newland said. “We’ve got to manage these antibiotics in a very appropriate manner or you’re not going to have them in the future.”

— Reporter: 541-633-2162, mhawryluk@bendbulletin.com