Seattle author tells a story of gender dysphoria

Published 10:56 am Friday, January 27, 2017

- (Submitted photo)

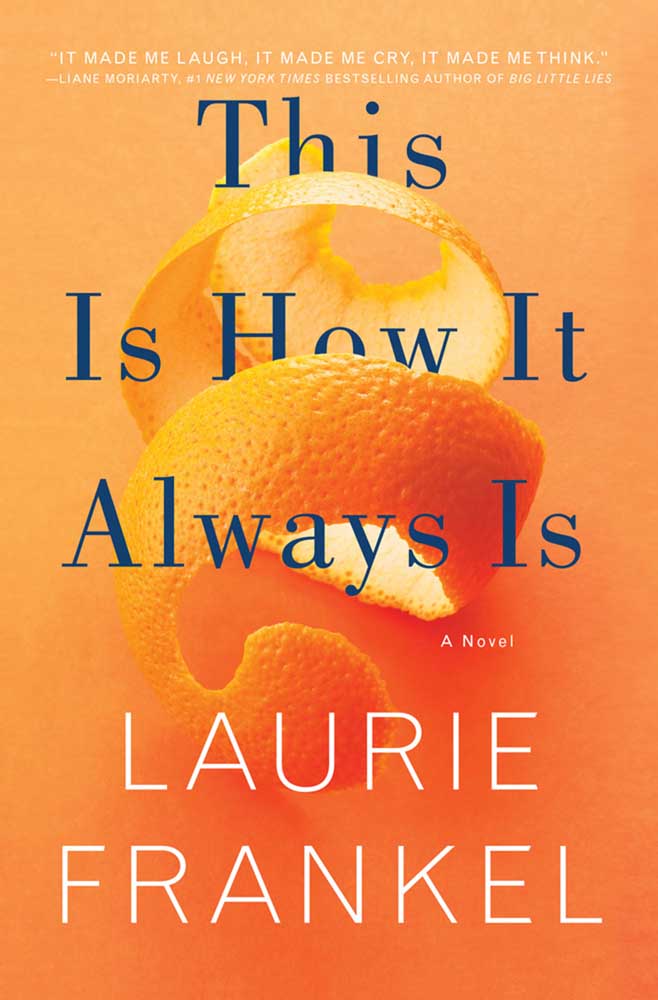

“This is How It Always Is”

by Laurie Frankel (Flatiron books, 337 pages, $19.72)

Trending

They put a spoon under the bed because German folklore said it would help produce a girl. Turned the mattress so that it faced east-west instead of north-south, which the Talmud said encouraged sons.

It all worked, but in a roundabout way. Nine months after the spoon and the directional switch, Rosie Walsh and her husband, Penn, became the proud parents of a boy named Claude who, when he was 3, declared that he wanted to be a girl.

“OK,” Penn said.

“You can be anything you want when you grow up, baby,” Rosie said.

And so begins “This Is How It Always Is,” Seattle author Laurie Frankel’s new book about a family navigating the unexpected turns that come when a child states with unflinching certainty he (or she) belongs in a different body, and wants to transition.

Frankel has taken the adage “write what you know” to heart: “This Is How It Always Is” was inspired by her experiences with her own daughter, now 8 and in the third grade.

Trending

Last fall, Frankel wrote a New York Times “Modern Love” column titled “From He to She in First Grade.”

It all started with a puppet theater and chest of dress-up clothes she and her husband bought for their theater-loving son. They included high heels, a straw hat and a sparkly green dress for his female playmates. The boy plucked the dress from the chest and put it on.

“In a sense,” Frankel wrote, “he never took it off.”

And while the column touched on what happened when their child decided to wear a dress and sandals to the first day of school, “This Is How It Always Is” goes far beyond, exploring how a gender transition affects and changes a family and how it relates to the world.

At its very heart, the book delves into the many ways parents love their children — for better, for worse, but always with the best intentions.

“The obvious conflict is between parents who want to be accepting of (gender dysphoria) in their children, and parents who want to get rid of this,” Frankel said.

Even when they are accepting, she said, they may have different approaches.

“Once we agree that we are going to love and accept this child, then how do we proceed?” Frankel asked. “Do we drug her? Do we operate?

“The impulse to protect the child is paramount,” she said. “And the issue of how to protect the child is much more complicated — in a good way.”

These are real-world conversations that we are just starting to have, Frankel said, which left her room to explore in her writing.

And yet, the issue of transitioning seems to be less complicated for the children going through it. Their minds are clear.

“This is the first generation of kids for whom this is happening, and it’s a wonderful thing,” Frankel said. “It doesn’t have to come to being desperate, an ‘I have to do this, or else I am going to die.’ Until this generation, it’s been a story of trauma and desperation.

“My daughter is very clear in a way that is muddled for me,” Frankel said. “I see everything that is scary about it and she doesn’t see any of that.”

Frankel praised her daughter’s school for their help with and support of her transition.

“She didn’t need much from them, and they have treated it like it’s not a giant deal,” Frankel said. “They felt that she was at an age old enough to make decisions for herself,” whether it be which bathroom she uses, or how to tell her classmates.

“It was a transition that everybody grew along with,” she said.

Frankel, 43, is a native of Baltimore who studied English literature. For a while, she taught at a community college.

“Being an author was never the plan,” she said. “It was the fantasy, but never seemed like a realistic possibility for a lot of years.

“But you never know if you can write a novel until you write a novel.”

“This Is How It Always Is” is Frankel’s third.

Her first book, “The Atlas of Love,” has been optioned for television.

Her second, “Goodbye for Now” — about a couple who create and market an algorithm that allows people to stay connected, via email, with loved ones who have died — has been optioned for film. The filmmakers are in talks with actors and directors, but Frankel doesn’t know much beyond that. Which is fine with her.

“For me, it’s very interesting to watch and it’s one part of the whole book process that I don’t feel overly invested in,” she said. “I feel like this movie is not my problem.

“If it happens, I’ll be thrilled. If it doesn’t, I’ll be fine.”

For now, she is eager to bring her new book to people involved in a loved one’s transition, and those who come to the issue cold.

“I hope that everyone will read this book, that it will appeal to anyone,” she said. “That question of how you love and how you face challenges in your life and your family. How you protect by also nurturing.

“These questions are being asked by everyone,” she said. “And my book is a full fleshing out of ideas. I hope that people will read it and come to a fuller understanding.”