Oregon liver cancer deaths soaring

Published 2:19 pm Thursday, February 2, 2017

- Oregon liver cancer deaths soaring

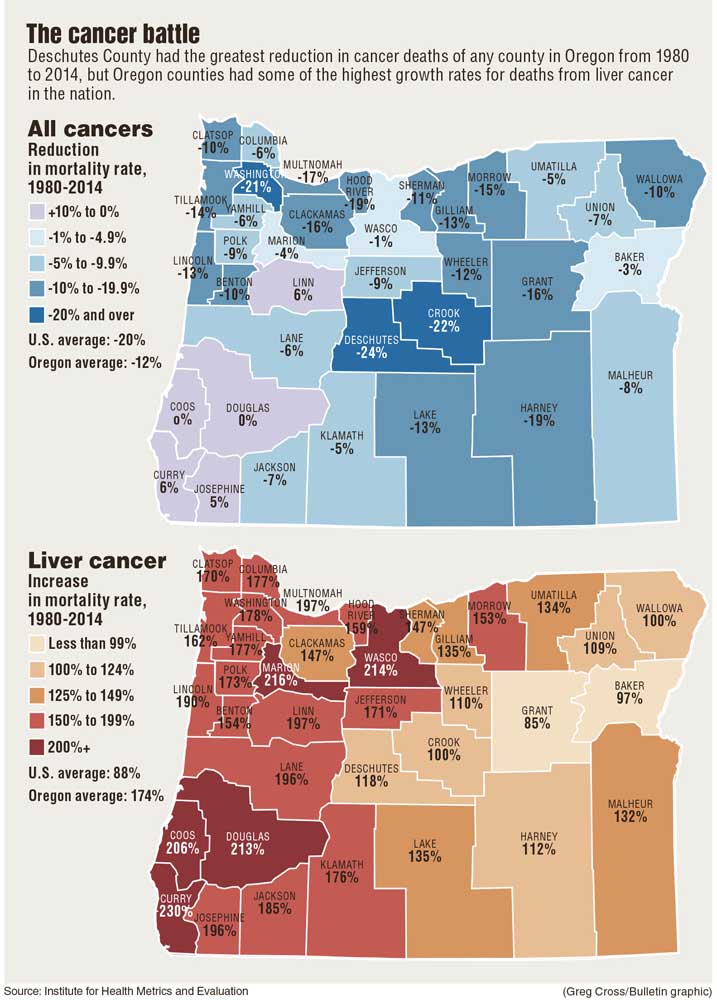

Liver cancer deaths in Oregon are growing at twice the national rate, likely due to a high prevalence of hepatitis C infections.

Oregon once boasted a liver cancer death rate 33 percent lower than the U.S. average. But over the past 35 years, liver cancer deaths in Oregon have risen so fast, the state has almost entirely closed the gap.

According to data released Tuesday by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, 6.81 out of every 100,000 Americans died of liver cancer in 2014, an increase of 88 percent since 1980. In Oregon, the death rate was 6.74 percent, representing a 174 percent increase.

Seven out of the 10 U.S. counties with the fastest growth in liver cancer deaths are in Oregon, with several other of the state’s counties ranking close behind. Every county in Oregon had an above-average increase in its liver cancer death rate, except for Grant County. The institute reported mortality rates for 29 types of cancer by county from 1980 to 2014. They found that while the overall cancer mortality rates dropped by 20 percent nationwide, those gains varied considerably from county to county, and by cancer.

Dr. Ali Mokdad, the lead author of the analysis, attributed those variations to four main factors: socioeconomic status, access to medical care, quality of medical care and risk factors within the population.

Individuals in more affluent areas, he said, are more likely to be educated, and to understand the risks around cancer, to seek medical care and to adhere to medical advice. Similarly, those groups have better access to medical care and are more likely to be adequately insured. Quality of medical care, including how early diagnoses occur and whether proven treatments are provided in a timely manner, also differs greatly from county to county.

But the most important component, Mokdad said, was individual risk factors, including lifestyle behaviors such as smoking, diet and exercise.

“When you look at lung cancer, it’s highest where there is a lot of smoking,” Mokdad said. “When you look at, liver cancer, it’s a combination of risk factors, which is alcohol, unfortunately, cirrhosis, hepatitis C. All of these conditions are prevalent and led to this increase in Oregon.”

Hepatitis and cancer

Dr. Barry Schlansky, a liver cancer specialist with Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, said over the past few decades 90 percent of liver cancer patients have had cirrhosis, mainly driven by hepatitis C infections. Hepatitis C infections are common in the baby boomer population, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recommend that those born between 1945 and 1965 be screened for the virus.

Hepatitis C is transmitted through blood, semen or other bodily fluids, primarily through needle sharing or sexual contact.

“Hep C takes decades to cause cirrhosis of the liver, so what we’re seeing is many people who are now in their 60s and their 70s have cirrhosis. Many don’t know they have it, because until cirrhosis becomes advanced, it does not cause any symptoms,” he said. “And that is the main risk factor for developing liver cancer.”

A 2015 report from the Oregon Health Authority found that the prevalence of hepatitis C infection in Oregon was 50 percent higher than the national rate in 2007 to 2011, and that 64 percent of those infected contracted through the virus through intravenous drug use.

That report found that deaths attributed to hepatitis C had risen steadily over the previous decade and has surpassed the number of deaths from HIV.

Liver cancer has a poor prognosis, with five-year survival rates for localized cancer of 31 percent. Once the cancer has spread beyond the liver, survival rates drop to 11 percent.

It takes decades for a hepatitis C infection to progress to cirrhosis and then to liver cancer, and until recently, treatments for hepatitis C were largely ineffective.

“These aren’t newly infected people, these are people who are just maturing in their disease,” said Dr. Kent Benner, a gastroenterologist with the Oregon Clinic in Portland.

When baby boomers with hepatitis C were in their 30s and 40s, about 10 to 15 percent had cirrhosis, he said. Now that they’re in their 60s, the rates of cirrhosis and consequently liver cancer are much higher.

But in 2014, new drugs were approved that can clear the infection and drastically reduce the risk of liver cancer.

“With these new meds, we can treat all these people and the data looks like there’s a 75 percent drop in cancer risk once you clear the virus,” Benner said. “So it makes sense to identify these people and get them treated.”

There are an estimated 95,000 Oregonians living with hepatitis C infections, although up to half have never been screened and don’t know they’ve been infected. Even when diagnosed, many will have trouble accessing treatment. The new hepatitis drugs have been expensive, and many public and private insurance companies, including the Oregon Health Plan, have limited access only to the sickest patients.

“Things are really changing here, but it’s a big battle to get people treated,” Benner said.

The next big thing

Schlanksy said computer modeling has shown that as baby boomers age and more are cured of hepatitis C, the incidence of cirrhosis is expected to peak later this decade, and that liver cancer cases and deaths should peak around 2020 then start to fall.

Some of those gains, however, could be offset by the rise in fatty liver disease, that is associated with obesity, diabetes and high blood pressure — all of which have been on the rise in Oregon and the U.S.

“As we cure and identify people with hepatitis C, we’re finding an increasing burden from fatty liver disease and cirrhosis, which can also cause cancer,” Schlansky said. “That might be the next big thing. And we don’t have a magic bullet for treatment for fatty liver disease like we do for hepatitis C.”

Liver cancer can also stem from hepatitis B infection, which is more common on the West Coast particularly among immigrants. Vaccines exist for hepatitis B, but only a fraction of adults have been immunized.

According to the Oregon Health Authority, in 2012, 8 percent of liver cancer patients in the state had chronic hepatitis B infection and 48 percent had chronic hepatitis C infections.

Oregon’s higher growth rates in liver cancer deaths may also reflect the state’s large rural regions where access to screening and specialty care are lower.

“There’s some evidence that the farther you live from specialty care, like gastroenterologists or liver specialists … some of these diseases, and even the precursor diseases like hep C and cirrhosis, may not be identified as early and treated as early,” Schlansky said.

Beating cancer

Liver cancer is one of the few cancers in which mortality is increasing. And Oregon’s high liver cancer rates slowed the state’s overall gains in reducing deaths from all cancers. Statewide, cancer deaths have decreased by 11.8 percent since 1980, well below the 20 percent decline nationwide.

Deschutes and Crook counties had the greatest reduction in cancer mortality among Oregon counties, at 24 percent and 22 percent. That likely reflects the changing demographics of Bend, which completed its transformation from a lumber town to a recreational mecca over the years of the study period, while significantly raising its average income.

“In Bend, the county that you’re in is a rich county,” Mokdad said. “The socioeconomic factors lead to more people having insurance, more early diagnosis, better treatment. That’s why you guys are doing better than anybody else.”

Dr. Linyee Chang, medical director for the St. Charles Cancer Center, said the gains also reflect the improvement of cancer treatment capacity in Central Oregon. The St. Charles Health System added radiation oncology in 1982 and over the years, the region has seen a steady increase in board-certified oncologists.

“I also wonder if the people who choose to retire in Central Oregon, Bend in particular, maintain an active lifestyle into their retirement years,” she said. “So they might be healthier, older population.”

Studies have shown that not smoking, getting regular exercise and eating a healthy diet, rich in fruits and vegetables, and limited in processed or red meat, can lower the risk for cancer. That may go a long way in explaining why Bend, which has an older population than many other cities in Oregon, has a lower cancer mortality rate.

— Reporter: 541-633-2162, mhawryluk@bendbulletin.com