Hiker treks 750-mile Oregon Desert Trail in just 3 weeks

Published 5:52 am Thursday, June 8, 2017

- Hiker treks 750-mile Oregon Desert Trail in just 3 weeks

Heather Anderson insisted that, this time, she would not be going for a record.

“I’m just going for a hike in the desert,” she said on May 15, shortly before walking off into the Badlands Wilderness east of Bend to start a trek of more than 800 miles.

Anderson — who owns the unsupported speed records for thru-hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, the Appalachian Trail and the Arizona Trail — is set to complete her hike of the Oregon Desert Trail by Tuesday or Wednesday.

She is also hiking the ODT unsupported, meaning she has no crew to help her. She sent boxes of food and supplies ahead to five different towns along the way, and she has a filtering device that allows her to drink water from cattle tanks and streams.

Anderson, 35 and an online personal trainer from Seattle, first discovered her love of hiking in the desert while working a summer job at the Grand Canyon during college. She was about 50 pounds overweight at the time, she said, and hiking helped mold her into prime shape. She has not stopped since.

“The desert is where I started hiking, so I definitely have a special place in my heart for desert areas,” Anderson said. “I like hiking pretty much everywhere, but the desert is kind of a special place for me.”

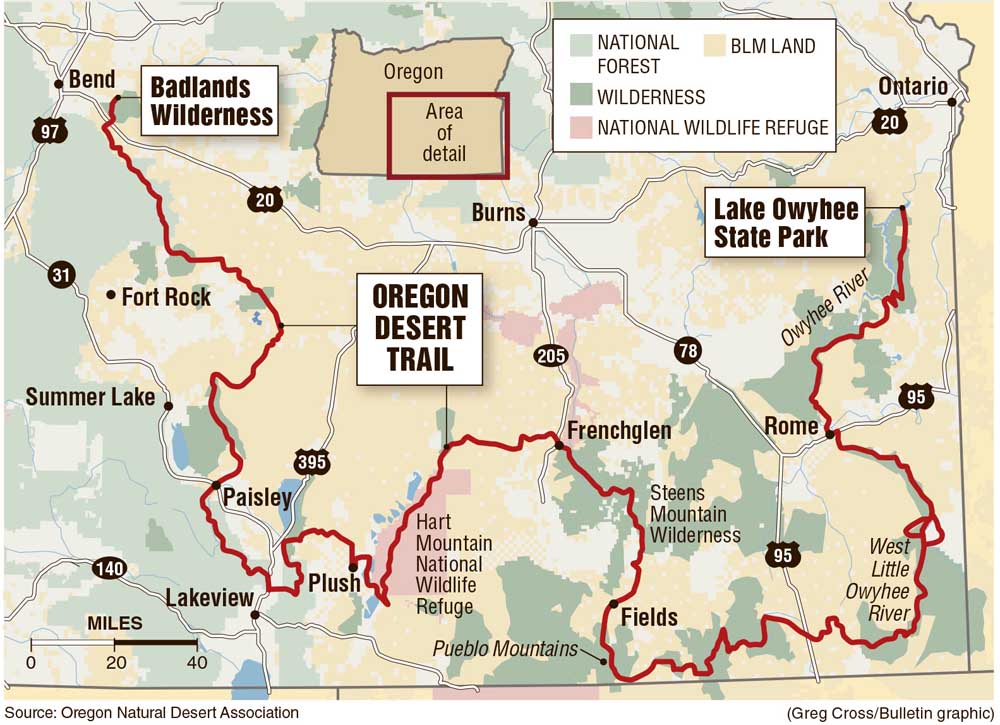

The 750-mile Oregon Desert Trail, established by the Bend-based Oregon Natural Desert Association (ONDA) over the past six years, is a route that connects wilderness-quality lands of Oregon’s High Desert. The western terminus is in the Badlands near Bend, and the eastern terminus is at Lake Owyhee State Park near the Oregon-Idaho border. The ODT is not a continuous piece of singletrack trail, but a GPS route over existing trail, dirt roads and areas where walking cross-country through the desert is possible.

Highlights of the route include the Diablo Rim just east of Summer Lake, the Fremont and Abert Loop, Steens Mountain, Hart Mountain National Wildlife Refuge, the Pueblo Mountains south of Steens Mountain, and most spectacular, the West Little Owyhee River Canyonlands in Oregon’s far southeast corner.

This past Tuesday, Anderson and her boyfriend Adam Lint, also from Seattle and accompanying Anderson on the hike, were expected to reach the Oregon-Nevada border town of McDermitt.

This summer, after completing the ODT, Anderson plans to thru-hike the Continental Divide Trail — a 3,100-mile route along the Rocky Mountains from Canada to Mexico — for the second time. She will not be vying for an unsupported record there either, because it is a route and not a specific trail, much like the ODT.

“I feel like with routes there really are no records, because you can choose your own path,” Anderson said. “It would be kind of meaningless. PCT (Pacific Crest Trail) and AT (Appalachian Trail) are very specific trails.”

In 2015, Anderson thru-hiked the 2,168-mile AT, from Mount Katahdin in Maine to Springer Mountain in Georgia, in 54 days. In 2013, she completed the PCT, from Mexico to British Columbia, in 60 days, 17 hours, and 12 minutes. Last fall, she completed the 800-mile Arizona Trail in 19 days, 17 hours, 9 minutes.

In her early 20s, Anderson thru-hiked the AT, PCT and Continental Divide. A few years ago she started to push her limits and go faster and faster — without support.

“That’s just a different twist on it,” she said. “I like to feel self-reliant for sure. I know I’m in control of the situation.”

Anderson is hiking light and fast, with a fully enclosed single-person tent and a zero-degree sleeping bag for those cold desert nights. Her phone has a GPS app for navigations, and she has a solar charger and two external battery packs to charge her phone. She eats dehydrated food, so no need to pack cooking gear.

Renee Patrick, the Oregon Desert Trail coordinator for ONDA, has been hard at work creating more resources for ODT hikers and adding alternate route options. The recently updated Oregon Desert Trail Guidebook is available online at onda.org and includes route descriptions, section overview maps and elevation profiles.

Patrick, who last year became the 10th person to thru-hike the ODT, said that this year there is more interest in hiking the ODT than ever. Access to drinking water is the biggest challenge facing ODT hikers, who can either cache water or filter water.

“You have to be willing to drink nasty water,” said Patrick, smiling. “I think any water in the desert is good water. You can’t be that picky if you’re doing a desert route because that’s just the nature of the desert.”

Patrick added that more ODT thru-hikers are set to start out in the next few weeks, and several more intend to hike the trail in the fall.

“There’s lots of section hikers, too,” Patrick said. “I’m also looking at places you can boat, or ski, or bike, or horseback ride. You don’t have to hike it all. There’s parts you can bike.”

The most challenging section of the ODT is the West Little Owyhee River in Malheur County, according to Patrick, an experienced paddler who navigated much of the river on her pack raft.

“It’s amazing and beautiful, and worth the struggle it is to make it through there,” she said. “It’s so remote. You’re the farthest from help there. A route like this you have to pay attention to stay found, and that leads to a higher level of engagement with your surroundings. At the heart of it is finding that connection with the landscape.”

In addition to her hiking exploits, Anderson is working on climbing the 100 highest peaks in Washington, most of them in the North Cascades.

“I just love being out in the wilderness,” Anderson said. “To me it’s home. It’s just where I feel like I belong, so I try to maximize the amount of time I spend out there.”

— Reporter: 541-383-0318,

mmorical@bendbulletin.com

“The desert is where I started hiking, so I definitely have a special place in my heart for desert areas.”— Heather Anderson