Study: Oregon docs not catching lead poisoning

Published 8:06 am Thursday, June 22, 2017

- Study: Oregon docs not catching lead poisoning

Central Oregon pediatricians take vastly different approaches to checking kids for lead exposure.

Many follow the Oregon Health Authority’s recommendations, which direct doctors to take parents through a questionnaire when asymptomatic patients hit ages 1 and 2. If they answer ‘yes’ or ‘don’t know’ to any of the risk factors, such as living in an old home or being from a low-income family, the agency urges doctors to perform blood tests — the definitive measure for lead exposure.

At St. Charles Health System’s family care clinics, by contrast, pediatricians have taken a decidedly more aggressive approach: All patients receive blood tests at ages 1 and 2.

“It’s just better to be cautious than not,” said Dr. Sarah Morrison, a pediatrician in St. Charles’ new family care clinic on Bend’s south side.

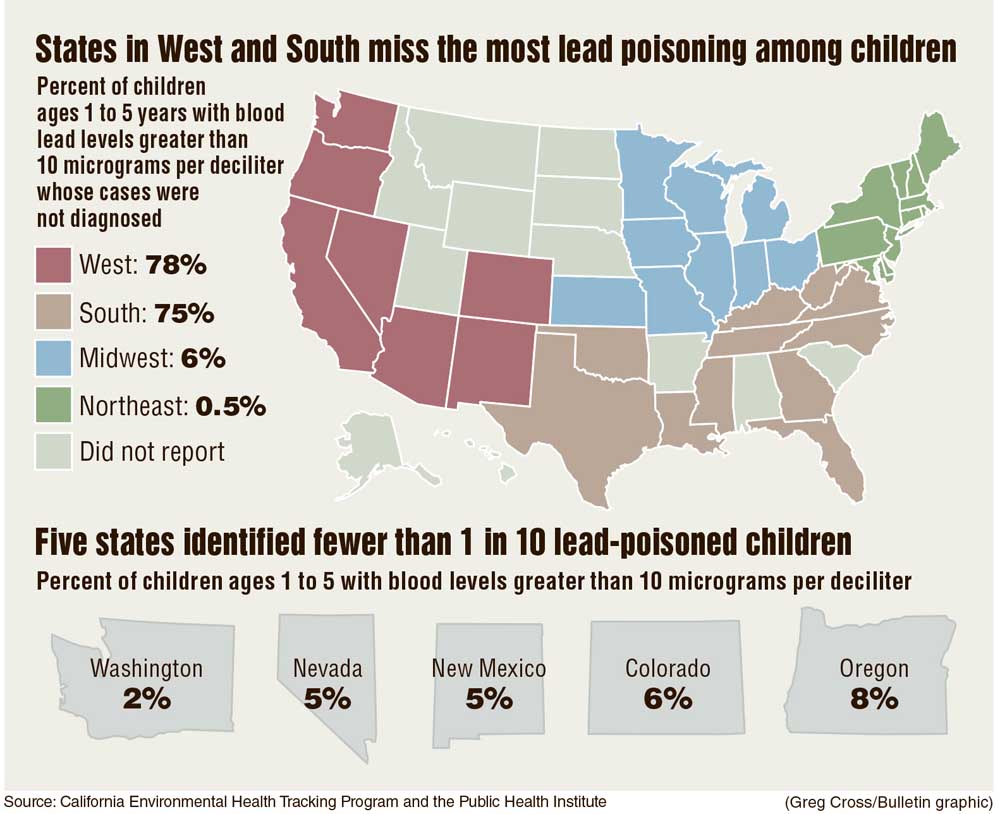

A new study in the journal Pediatrics suggests the latter approach — performing blood tests on all kids — may be warranted. Researchers found that medical providers identified only about half of all estimated cases of elevated blood lead levels in U.S. kids between 1999 and 2010. Western states participating in a federal reporting program missed 78 percent of cases — more than any region in the country, according to the study.

The study calls out Oregon as having identified the fifth lowest percent of lead poisoning cases: only 8 percent were diagnosed by providers.

Lead is a neurotoxin for which there is no safe level of exposure. Lead poisoning is known to damage the nervous system, causing cognitive impairments, attention deficits and increased impulsivity.

Children ages 1 to 5 are considered to be at highest risk for exposure because of their tendency to crawl and put objects in their mouths. Their developing brains are also the most vulnerable to lead’s toxic effects.

The Pediatrics study used data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys to estimate prevalence based on risk factors for lead poisoning, such as aging housing and low incomes.

Based on that data, the researchers estimated 1.2 million cases of elevated blood lead levels occurred in the U.S. between 1999 and 2010. They concluded that under-testing for lead poisoning in the U.S. is “endemic” in many states.

Dr. Eric Roberts, one of the study’s authors and a research scientist with the Oakland, California-based Public Health Institute, said in some parts of the country, providers are convinced lead exposure is not an issue. They point to their state or local data, but that’s typically only based on a tiny proportion of kids that get tested, he said.

“If the practitioners don’t already test aggressively, there won’t be any sign that there are children at risk in their area,” Roberts said.

The perception of new

The epidemic of lead poisoning from tainted water in Flint, Michigan, raised public awareness about lead hazards and helped expose problems in many other U.S. communities. While the most reported cases are still in the Northeast and Midwest, Roberts urged providers in other regions not to assume they’re not at risk.

In California, for example, “We tend to think of ourselves as a new state,” Roberts said. “Everything around here is new.”

Actually, he said, data points out much of the housing was built before the 1978 U.S. ban on lead-based paint.

The perception of newness also seems to permeate Central Oregon’s provider community. That’s how Dr. Kristi Nix, a pediatrician with High Lakes Health Care, described Bend.

“Bend is a young enough community that it’s relatively uncommon to have an environmental risk or a known environmental risk,” she said.

But records from the Deschutes County Assessor’s Office show 23 percent of the county’s residential buildings — about 17,600 total — were built before 1978, the year lead paint was banned. That figure includes multidwelling units like apartment buildings and condos.

Nix follows the OHA’s protocols: She uses the questionnaire with families and performs blood tests when they turn up risk factors.

“I always kind of think about when we’re doing that questionnaire whether or not we’re missing kids because we aren’t doing routine blood testing,” she said.

Nix estimates she performs an average of one blood test per month to check for lead exposure. In her eight years of working here, she’s never had a child test positive.

At Central Oregon Pediatric Associates, pediatricians screen kids using the OHA’s questionnaire at 9, 12 and 18 months old. Even then, the number of kids who ultimately test positive for lead exposure is low — maybe two or three in the past couple of years, Dr. Caroline Gutmann, a COPA pediatrician, said. One was a child who lived in an old farmhouse east of Bend and the other had moved from an older home in Portland.

“There haven’t been many,” she said.

The proportion of kids tested for lead exposure in Oregon has hovered between 4 and 5 percent for years, said Ryan Barker, the OHA’s lead program coordinator. The OHA would like to boost that to match the national rate of about 10 percent, he said.

Providers are supposed to report the results of any lead tests, negative or positive, to their county health department or the OHA, which then reports them to the federal government. But Barker said many providers aren’t aware of those reporting requirements.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention maintains annual county-level data on the number of cases of lead-exposed children. In 2015, the most recent year for which data are available, there weren’t enough tests from Deschutes, Crook or Jefferson counties to meet the CDC’s reporting threshold, which is five tests per county.

‘We’re not cautionary’

The OHA’s approach to lead assessment aligns with that of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Dr. Jennifer Lowry, chair of the AAP’s Council on Environmental Health, said while it’s true that not enough children are being tested for lead, there are too many hurdles to performing blood tests on everyone at ages 1 and 2.

For one, insurers don’t always pay for the tests. And even when kids test positive, county health departments don’t always have the resources to help families identify and get rid of exposure sources in their environments.

What’s more important, Lowry said, is preventing lead exposure from happening in the first place by educating about the dangers of old homes, certain occupations and household items.

“Unfortunately, what we do with lead now is we’re very reactionary,” she said. “We’re not cautionary.”

Sometimes, doctors find parents themselves are resistant to having blood drawn from their young child. That’s why Morrison’s St. Charles clinic is getting equipment to perform finger stick tests that are much less invasive than a blood draw. If that test turns up positive, it still needs to be confirmed with a blood test.

Morrison, who moved from Miami to work in the new Bend clinic, said universal blood tests were the norm in her previous practice. Same with a fellow pediatrician in that clinic, who moved from California.

“Both of us were just really blown away when we were getting these patients that didn’t have any testing,” said Morrison, who has worked as a pediatrician for 18 years.

The biggest exposure source in Oregon is lead-based paint particles, which chip off of walls and fall on the floor or ground inside or outside of homes. Exposure risk is especially high while a home is being renovated. Although lead gasoline is no longer in use, exposure can also come from working on old cars, bullets, stained glass and certain pottery, among other things.

If a child tests above 5 micrograms per deciliter, it triggers a county health department to inspect the family’s home and identify and potentially help mitigate the exposure source, Barker said.

For his part, Roberts, the author of the Pediatrics study, would like to see universal blood tests on all kids starting at age 1.

“Our decisions about what kids are at risk and require testing is based on a lot of assumptions that we have that are not backed up by data,” he said.

—Reporter: 541-383-0304,

tbannow@bendbulletin.com

Oregon Health Authority lead exposure questionnaire

State health officials recommend providers ask parents the following questions when their children reach ages 1 and 2 and perform blood tests if they answer ‘yes’ or ‘don’t know’ to any of the questions.

1. Has your child lived in or regularly visited a home, child care or other building built before 1950?

2. Has your child lived in or regularly visited a home, child care or other building built before 1978 with recent or ongoing painting, repair and/or remodeling?

3. Is your child enrolled in or attending a Head Start program?

4. Does your child have a brother, sister, other relative, housemate or playmate with lead poisoning?

5. Does your child spend time with anyone that has a job or hobby where they may work with lead? (Examples: painting, remodeling, auto radiators, batteries, auto repair, soldering, making sinkers, bullets, stained glass, pottery, going to shooting ranges, hunting or fishing.)

6. Do you have pottery or ceramics made in other countries or lead crystal or pewter that are used for cooking, storing or serving food or drink?

7. Has your child ever taken any traditional home remedies or used imported cosmetics? (Examples: Azarcon, Alarcon, Greta, Rueda, Pay-loo-ah, Thanaka, or Kohl)

8. Has your child been adopted from, lived in or visited another country?

9. Do you have concerns about your child’s development or behavior?

Health officials also urge providers to consider blood tests if children of any age show the following symptoms:

• Behavioral problems: aggression, hyperactivity, attention deficit, school problems, learning disabilities, excessive mouthing or pica behavior and other behavior disorders.

• Developmental problems: growth, speech and language delays and/or hearing loss.

• Symptoms consistent with lead poisoning: irritability, headaches, vomiting, seizures or other neurological symptoms, anemia, loss of appetite, abdominal pain and cramping or constipation.

•Ingestion of foreign body.