Memory care facilities multiplying in Oregon

Published 3:22 pm Tuesday, October 3, 2017

- Memory care facilities multiplying in Oregon

For some dementia patients, the best medicine is a structured day. At Touchmark at Mount Bachelor Village, Angela Stewart fills memory care residents’ schedules with exercise classes, field trips and music.

“I always say bored equals behaviors,” said Stewart, memory care administrator at the Bend facility. “If someone is bored, they’re going to have increased confusion, loneliness and behaviors.”

But that takes a lot of planning and staff. And the residents themselves require a great deal more help with daily tasks like eating, bathing and toileting than their counterparts in residential care.

It perhaps comes as no surprise, then, that research out of Portland State University found memory care facilities in Oregon tend to be more expensive than residential care and assisted living facilities.

That doesn’t seem to affect demand, though. The university’s research also found the number of memory care facilities in Oregon are growing rapidly — up 79 percent this year compared with 2006 — and they tend to be more full than other types of long-term care.

At least 62,000 Oregonians aged 65 and older currently are living with Alzheimer’s disease, a number that’s expected to grow to 84,000 by 2025, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

To prepare, Oregon’s Department of Human Services commissioned PSU and Oregon State University to prepare annual reports on the availability, cost and other characteristics of long-term care in the state.

“We’re looking at this critically and trying to make sure we have a system that will support those people in the coming years and decades,” Ashley Carson Cottingham, director of DHS Aging and People with Disabilities, told attendees at an event unveiling the research earlier this month.

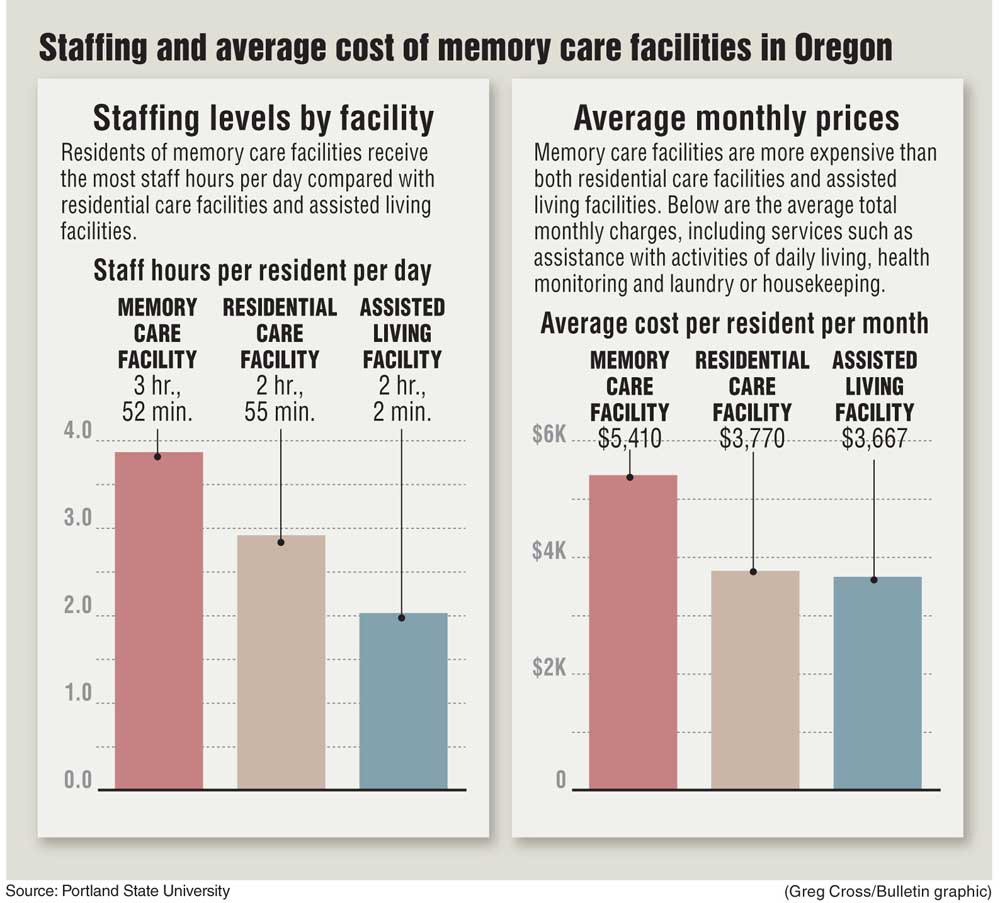

The average monthly stay in a memory-care unit in Oregon costs $5,410, including services that cost extra like health monitoring, assistance with daily living and laundry, according to PSU’s report. The same thing at a residential care facility costs $3,770. At an assisted living facility, it’s $3,667.

That’s partly because memory-care residents require more time and attention from staff members. PSU also found memory-care staff members in Oregon spend 3 hours and 52 minutes per day with each resident, on average, compared with 2 hours and 55 minutes in residential care and 2 hours and 2 minutes in assisted living.

Paula Carder, the report’s principal investigator and an associate professor in PSU’s Institute on Aging, said that’s because memory care residents tend to have higher levels of impairment and require more one-on-one attention. When it comes to activities like bathing, dressing or eating, it might take a staff member a few minutes to help someone who is not cognitively impaired.

“But for someone with dementia, it could take 20 minutes to do the same task because the person is either confused or scared or combative,” she said, “so it’s just more time intensive.”

Memory care facilities also need to have more advanced security systems and safety features around their buildings, which could also add to the cost, Carder said.

PSU’s data came from surveys of memory care, residential care and assisted living facilities, together referred to as community-based care.

Aggression can be a challenge with people who have dementia, and Stewart said Touchmark works hard to assess every resident’s tendency toward aggression and prevent escalations between residents. Of the community-based care facilities PSU surveyed, 18 percent said they had issued move-out notices to residents within the past 90 days because they had either hit or acted in anger against another resident.

Stewart said Touchmark avoids move-out notices at all costs and has never issued one because of aggression.

“This is their home, so we definitely don’t want to be moving them out,” she said.

PSU also found that 56 percent of community-based care facilities perform fall risk assessments on every resident as a standard practice. Carder said she doesn’t think it’s necessary to assess every resident’s risk, as some are relatively fit and just need help with certain tasks. It would be important for people with dementia and conditions like multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease, she said.

At Touchmark, everyone in memory care receives a fall risk assessment when they move in or if their condition changes, Stewart said. For residential care, that’s only necessary if they have a health condition that makes them vulnerable to falls, she said.

Oregon law requires community-based care facilities to employ or contract with a nurse. Of those that responded to PSU’s survey, 68 percent employed at least one full-time registered nurse and 20 percent employed at least one full-time licensed practical nurse or licensed vocational nurse. For its part, Touchmark employs several full-time RNs.

Most care, however, is provided by personal care staff members, which refers to anyone who provides hands-on care with bathing, toileting, feeding and other daily activities. These workers don’t have to be licensed or certified in Oregon, but they do need to be trained by the facility they work in, Carder said.

Only 60 percent of community-based care facilities responded to PSU’s survey, and Carder said she believes DHS would like to see a better response.

“To them, it’s a reasonable request for information,” she said.

Oregon State University also prepared a report on nursing facilities in Oregon, which in most cases provide transitional care to people before they return to the community after a hospitalization. Occupancy in nursing facilities has been decreasing in Oregon, from 72 percent in 2000 to 66 percent in 2016. Oregon has one of the lowest nursing facility occupancy rates in the country, the report found.

That’s by design, said Carolyn Mendez-Luck, an author of OSU’s report and associate professor in the college of public health and human sciences.

“Oregon has made a commitment to keeping people in the community and using community-based services rather than nursing facility services,” she said. “That could be another factor that affects occupancy.”

Deschutes County residents used nursing facilities even less than the rest of the state: occupancy rates were 53 percent, according to the report. The number of available facilities could contribute to that, or how often providers refer people to nursing facilities, Mendez-Luck said. The other possibility is that people here require less nursing care, she said.

“Certainly the health of the population, if it’s aging better, then that’s a natural less demand for nursing facility services,” she said.

—Reporter: 541-383-0304,

tbannow@bendbulletin.com