St. Charles takes $3 million hit on drug costs

Published 12:00 am Saturday, February 3, 2018

- St. Charles takes $3 million hit on drug costs

Efforts to rein in abuse of a drug discount program for hospitals that serve a high number of low-income patients could cost St. Charles Health System an estimated $3 million in revenue in 2018.

The 340B program, created by Congress in 1992, requires pharmaceutical manufacturers to give deep discounts to safety-net hospitals and health clinics. But hospitals can use those drugs for any of their patients seen in an outpatient setting, and often bill private insurance or government health plans for the full price of the drugs.

That spread creates added revenue, essentially providing a subsidy for safety-net hospitals that is not funded with taxpayer dollars.

All four St. Charles hospitals in Central Oregon benefit from the program, which provided about $9 million in combined discounts to the health system in 2017. St. Charles has budgeted for the resulting $3 million shortfall for 2018, but it occurs at time when the hospital system is projecting a tough financial year. The hospital system announced a set of layoffs and pay cuts in October in an effort to avoid a $25 million to $35 million shortfall this year.

“(The drug discounts) help to support our outpatient pharmacy, the medication therapy we provide and our anticoagulation clinic,” said Jenn Welander, chief financial officer at St. Charles.

The added revenue, she said, allowed the hospital to bump up its financial assistance, providing free care to families with incomes under 300 percent of the poverty level, and offering a 50 percent discount for those below 400 percent of the poverty level. St. Charles provided $4.8 million in uncompensated care in 2017, as part of $129 million in total charitable services..

But Welander said the 340B revenues were not earmarked for any specific purpose. Hospital officials said the bulk of the savings come from the St. Charles Cancer Center, where most medications are very expensive, brand-name therapies.

According to the Health Resources and Services Administration, which oversees the program, U.S. hospitals and clinics bought about $12 billion of discounted drugs in 2015, saving an estimated $6 billion.

But federal regulators and lawmakers — as well as drug companies who must cough up the discounts — have raised concerns about the rapid growth of the program, and whether all of the participating hospitals use the funds to help low-income patients.

The number of individual sites using the discount program grew from 8,600 in 2001 to nearly 35,000 in 2016, with many hospitals registering multiple sites. Part of the increase was due to the Affordable Care Act, which expanded the program to include rural hospitals and health clinics. The Medicaid expansion also meant many larger hospitals saw more Medicaid patients and thus qualified for the program.

“The 340B program is an essential part of the health care safety net, especially in our rural communities. In Oregon, I think that’s used appropriately,” said U.S. Rep. Greg Walden, R-Hood River. “There are indications that in some areas, there’s been bad behavior.”

Critics say the program has shifted from primarily assisting safety-net hospitals to providing a new revenue stream to hospitals that provide relatively small amounts of uncompensated care. And several studies suggest hospitals may be gaming the system to take advantage of the discounts.

The program has been expanding at the same time that hospitals have been purchasing community-based physician practices, particularly cancer treatment clinics, and many see a connection between the two trends. Hospitals have countered that in many cases, they were approached by cancer treatment clinics that were struggling to stay afloat, and that the acquisition of physician practices and community clinics by hospitals is being driven by a number of factors besides the 340B program.

Others argue the discount program encourages providers to choose higher cost therapies in which the spread between the discounted price and the reimbursement rate is greater, instead of lower-cost therapies that are just as good.

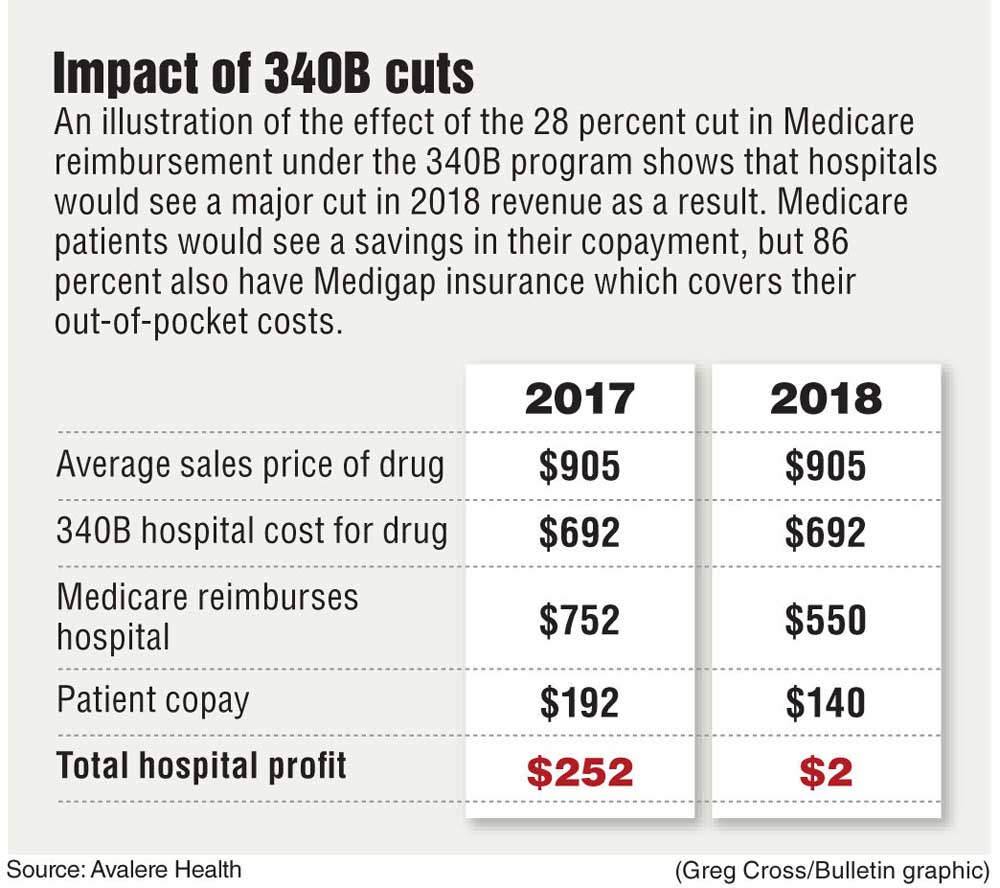

The Government Accountability Office, the Health and Human Services’ Office of the Inspector General and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission have raised concerns about the integrity of the program. That prompted the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to cut outpatient reimbursements to hospitals for the discounted drugs by 28 percent starting Jan. 1. A group of hospitals has sued to overturn the cuts.

Walden chairs the House Energy and Commerce Committee that has been investigating the 340B program and issued a report on its findings in January. The report concluded that the law passed by Congress did not clearly identify the intent or the parameters of the program. That makes it difficult to determine whether hospitals’ use of the discounts is consistent with the original intent or represents an abuse of the system. But the federal agency administering the program has little power to clarify the program and limited resources to audit participants.

“The law really lacks clarity about the purpose of the program, the transparency of the program and the accountability of the program,” Walden said.

Walden said the committee would be looking at the impact of the Medicare cuts as it deliberates on how to shore up the 340B program. That could include refining the definition of charity care, coming up with rules about how the revenues should be spent and establishing a way to track what hospitals are doing with the money.

His district includes 21 hospitals that get the discounts, but 17 are rural or critical-access hospitals, and thus exempt from the Medicare cuts. It’s mainly the larger hospitals in Bend and Medford that are affected.

The Medicare cuts were included in a broader rule whose overall financial impact had to be budget-neutral. That means reimbursements for other outpatient services will go up. According to an analysis by Avalere Health, 85 percent of U.S. hospitals will end up with a net increase in revenue as a result.

The Medicare cuts would also reduce copayments for Medicare beneficiaries receiving the discounted drugs, although other patients could face higher copayments for the outpatient services whose reimbursement rates were increased. However, the vast majority of those enrolled in Medicare also have supplemental Medigap coverage that shields them from any copayments.

According to the Oregon Association of Hospitals and Health Systems, some 40 hospitals participate in the 340B program statewide.

“The savings generated allow many of them to offer services that they otherwise might not be able to offer,” said Philip Schmidt, associate vice president for public affairs for the hospital group.

“In many hospitals, the program is seen as a core mechanism that ensures financial stability in supply cost management.”

Several members of the Energy and Commerce Committee have introduced legislation around 340B, and Walden said the committee would begin the legislative hearing process to consider those bills.

One option, he said, would be to freeze the program and not let more hospitals join until the new rules are in place.

While some hospitals have vehemently opposed any changes to the program, others have backed reforms, concerned that abuse of the program by some hospitals could undermine the program for all hospitals.

In a letter to Walden obtained by Politico magazine, Piedmont Healthcare executives warned that “too many hospitals are focused on getting 340B discounts to reap extra profits instead of serving poor and uninsured populations” and that the program is “helping some hospitals expand in ways that ultimately make healthcare more expensive.”

Hospitals have formed a lobbying group to protect the program, and Welander said, St. Charles CEO Joe Sluka has been active in that effort.

Mosaic Medical and La Pine Community Clinic also benefit from the discount program, but as federally qualified health clinics, are not facing any cuts this year.

—Reporter: 541-633-2162, mhawryluk@bendbulletin.com